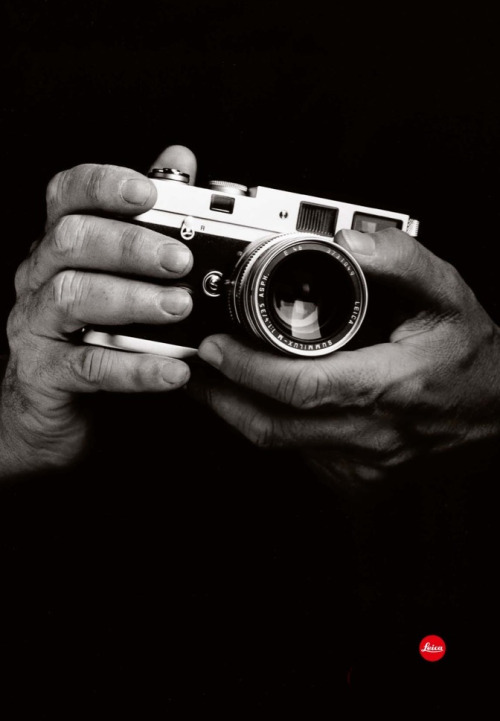

Sean Flynn’s Black Paint M2

This black paint Leica M2, serial number 1130008, was owned and used by US press photographer Sean Flynn, son of actor Errol Flynn. Flynn used this camera to cover the Vietnam War and Israel’s Six Day War. Flynn often accompanied US special forces units in hostile areas. On April 6th, 1970, Flynn with his fellow photojournalist Dana Stone motorcycled into Cambodia. Neither was ever seen again. It’s thought that both were kidnapped by the Vietcong and given to the Khmer Rouge before being executed. Sean Flynn was declared legally dead in 1984.

His M2 was found in his Paris apartment after his disappearance. Why he didn’t have it with him when he disappeared is anyone’s guess.

Sean Flynn with His Black M2 and Chrome Summilux

The camera, still in good working order, was auctioned off by Leitz Photographica Auctions in 2018 for an unspecified sum. It shows the obvious signs of wear of a black paint Leica used in extreme conditions. It was auctioned equipped with steel-rim Summilux 1.4/35 no.2166593 (from the last series of 200 lenses made in 1966). Attached to the camera was a short strap made from a parachute cord, with steel ring from a hand grenade.

Chasing the [B&W] Film Image

The Classic B&W Film Look – Shot with a Sigma DP2x

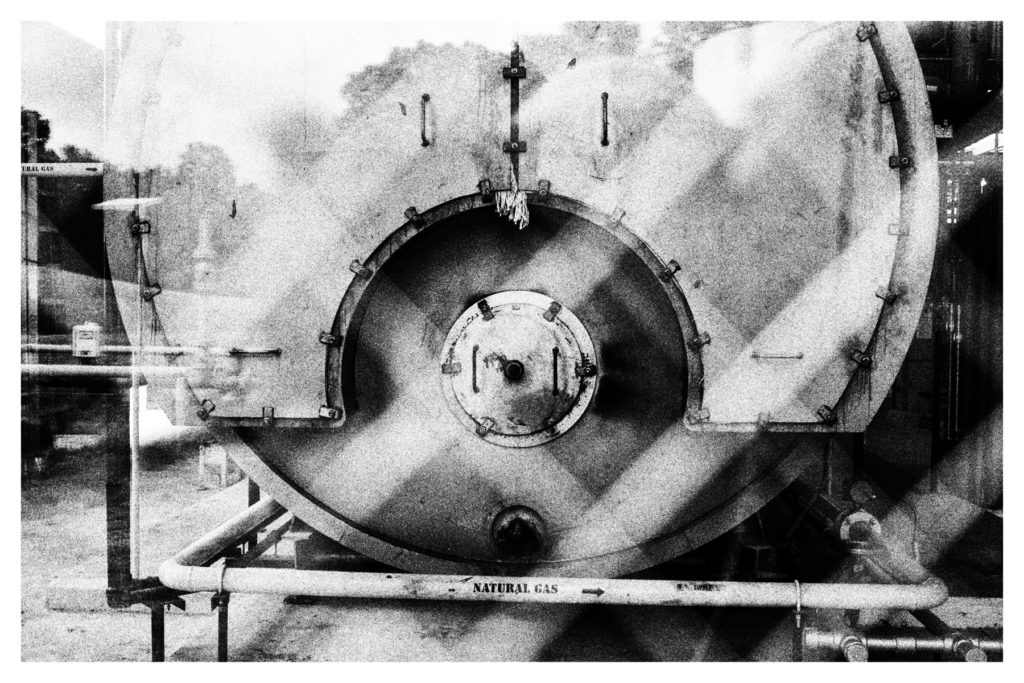

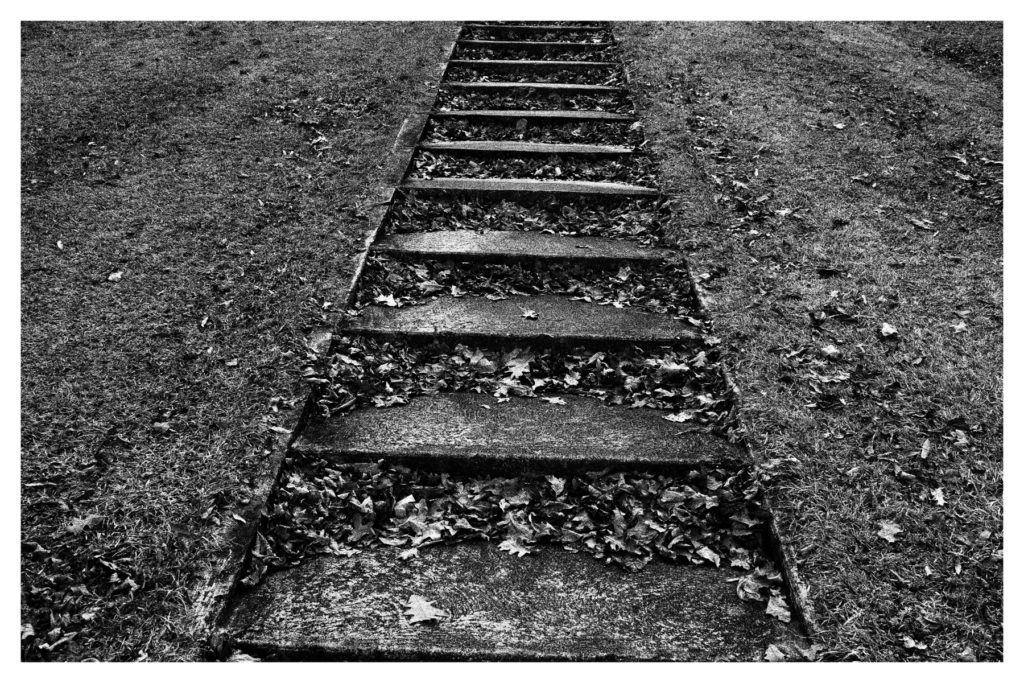

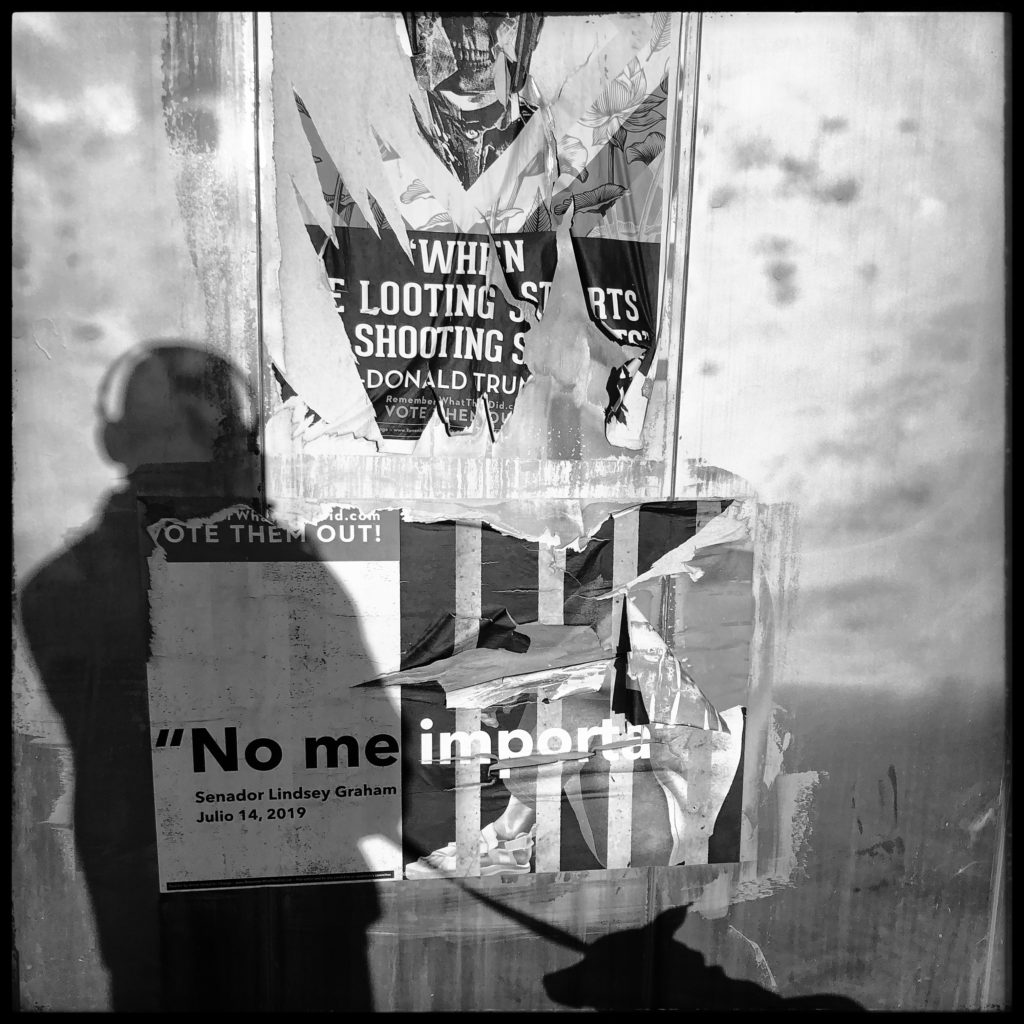

If I’ve made one concession to the digital age, it’s that it’s sent me on a quest to duplicate, via digital capture, the classic B&W film look. By ‘film look’ I mean the ’50s era Tri-X aesthetic. I’m not interested in grainless, subtle tonalities coupled with optical perfection. Leave that to digital B&W, almost all of which, to my eye, just doesn’t look very interesting. It looks thin and plastic, like it has no depth. I could be imagining things, but I don’t think so. The differences are real, and, at least to me, they matter. B&W photography, if it’s worthy of the name, should have a certain look. Think Robert Frank’s Americans, or Josef Koudelka’s Gypsies, or Trent Parkes’ Minutes to Midnight.

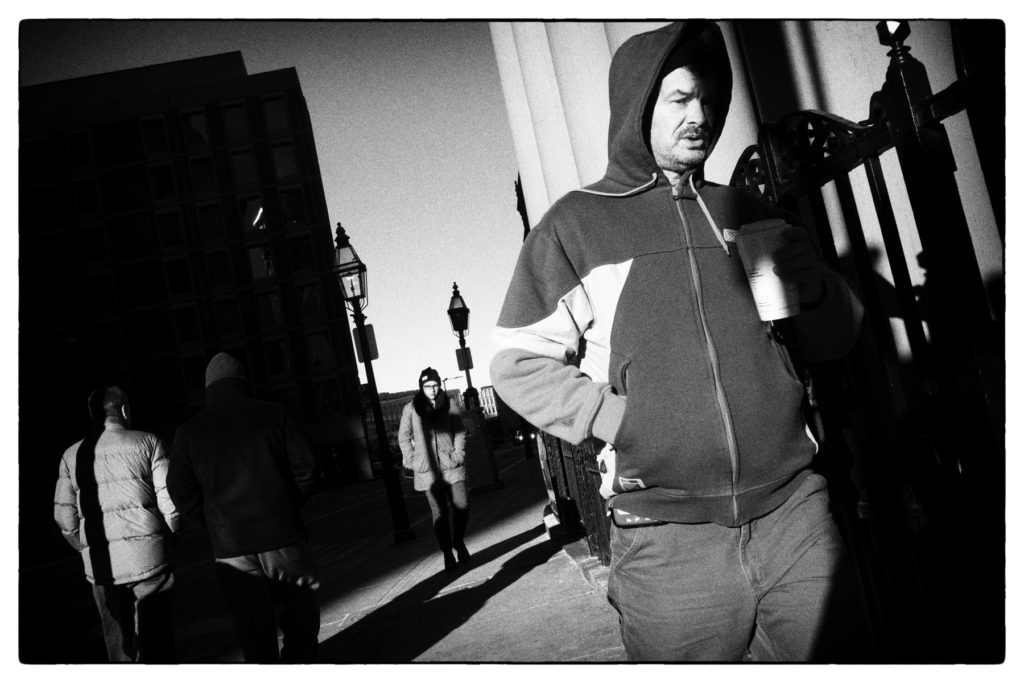

Above is a photo I took recently with a Sigma DP2x, post-processed in Silver Efex. To me, it’s a film image – the contrast, the grain, the tonality of Tri-X developed in Rodinal – about as close as I’m going to get without actually running a roll of Tri-X through my camera. So, it can be done. For comparison, I’ve posted a film snap below that exhibits the characteristics I’m looking to duplicate digitally. To my eye, these two photos could have come from the same roll.

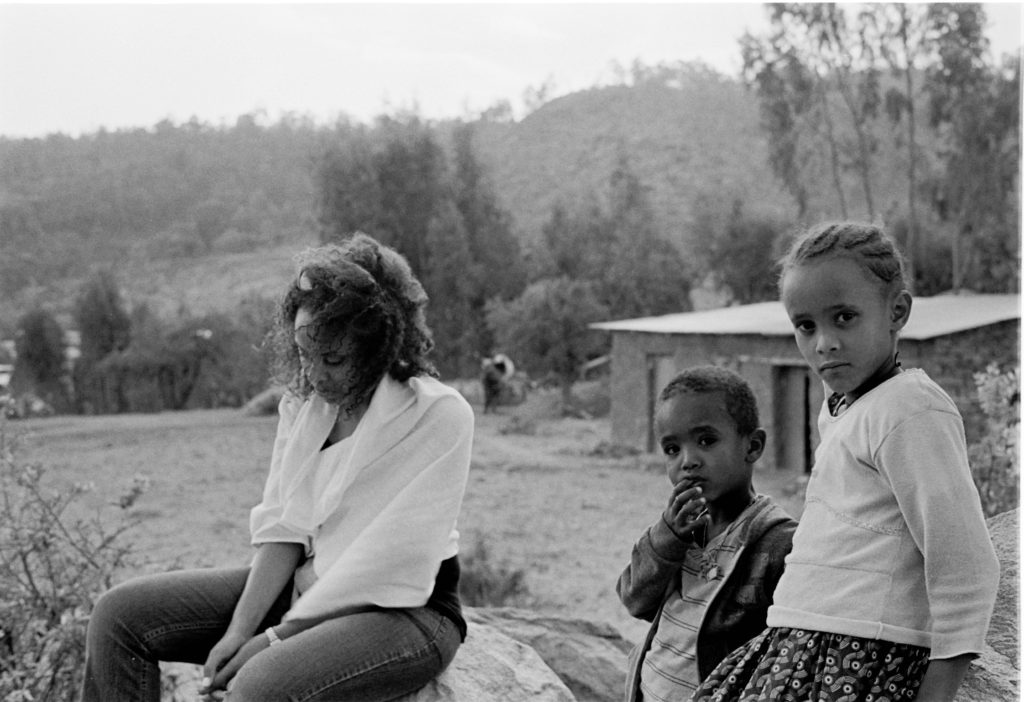

Valentina and Donna, San Francisco, 2016 – HP5 at 800 ISO.

*************

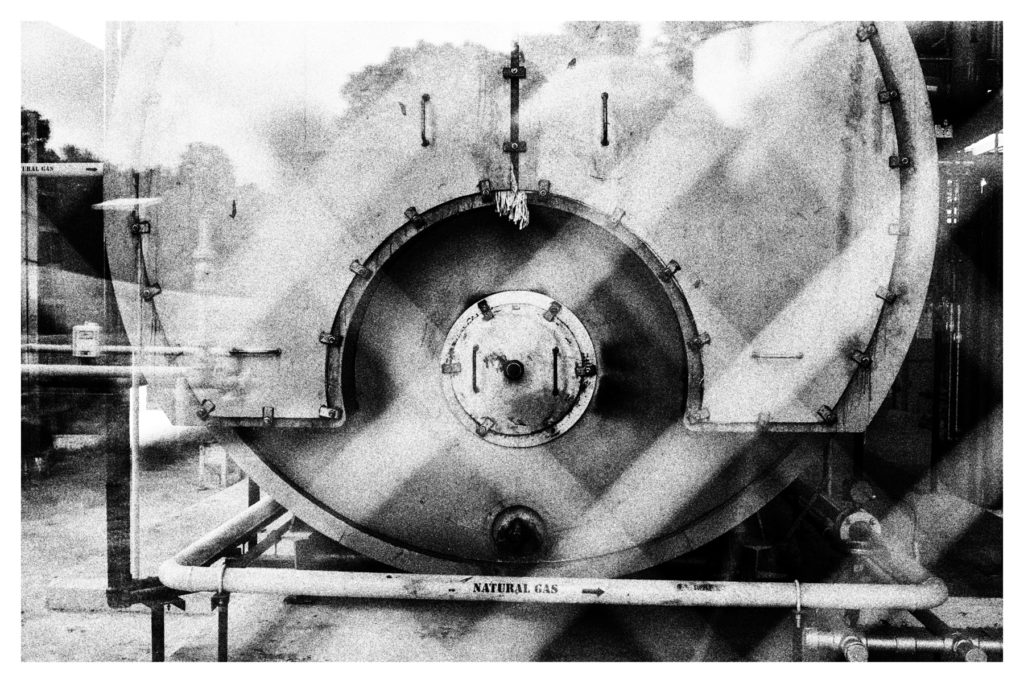

Tobacco Fields, Eastern North Carolina – Film or Digital? Hard to Tell (It’s a DP2x Silver Efex Conversion)

What I’ve learned [so far] can be distilled into a few simple observations: First, you’ve got to shoot RAW and run your files through film emulation software. No B&W jpegs using various in-camera film simulations. Pushing digital ISO and relying on digital noise isn’t going to get it either. I find Silver Efex to be excellent, especially using the Tri-X, HP5, Neopan 1600 and TMax 3200 presets as starting points.

Second, relatively low-resolution sensors give better film simulations; grain structure seems more accurate, tonalities more amenable to Tri-X contrast. 5-12 mpix seems to be the sweet spot. Something about higher resolution sensors – 24 mpix and above – translates into unnatural looking grain structure when post-processed, a look of having been added-on as opposed to being an organic characteristic of the output. It makes sense – 35mm Tri-x and HP5 aren’t about resolution so much as a particular grain patina. High-resolution output can’t be disguised with a simple grain overlay. The original Sigma Dp series – the 5 mpix Foveon – gives remarkably film-like grain output and tonality, printable up to 11×14 (which, ironically, is about the same limit of enlargement allowed by a 35mm negative, supporting the argument for the approximate equivalency of the Dp resolution to that of 35mm film), when run through Silver Efex by a discerning eye. It’s 35mm Tri-X developed in Rodinal in a digital box. Other sensors that seem to effectively simulate film output are the 10 mpix CCD sensor of the Nikon d200 and, my favorite, the 12 mpix Ricoh GXR M-mount. The beauty of this is you don’t need to spend $4000 on a Monochrom; you can pick up a d200 or d80 for next to nothing, and pre-digital Nikon primes are cheap as dirt.

One’s Film (HP5 2 800 ISO). One’s Digital (Ricoh GXR M-Mount).

Which leads me to my third generalization: film era optics produce better digital files for film emulation. Highly corrected modern digital optics are simply too sharp if you’re looking to replicate film. Film didn’t look that way, a function of less tack-sharp optics. Older lenses were designed using manual computation, are inclined to flare a bit and are often softer at the edges or have some vignetting, things you don’t see in modern, highly corrected optics. These optical characteristics are also a part of what we think of as the ‘film look.’

*************

I’ve recently bought the camera a CCD Monchrom. Leica marketed it as an evolution of B&W film photography in the digital age. They bundled a copy of Silver Efex with it, just in case. I’ve not had it long enough to make any valid comparisons, but first impressions are excellent. At the very least, it does capture B&W in a way unlike traditional digital B&W output. Below are two Monochrom snapshots run through the same emulation as the DP2x shots, followed by two similar DP2x shots.

The Photography of Jacques-Henri Lartigue

I’ve always had a soft spot for Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s amateur photographic work. For me, his childhood output constitutes one of the highlights of early 20th-century photography. Born in Courbevoie, near Paris in France in 1894, Lartigue took his first photographs at age 8. For him, photography was a revelation that would inspire him throughout his life: “It was a superhuman invention. I got it all! Colors! The sounds!”

Lartigue’s early vision – private memory as photographic subject – constitutes an authentic autobiographical diary of his family life in pre-WW1 France. His images are of an affectionate and happy family environment: parents, brother Zissou, grandfather Alfred (who was one of the inventors of the monorail system and also a playwright), uncles, aunts, cousins all handsome and well dressed. From the images we know that the Lartigues were well off socially – we are shown nannies, chauffeurs, loved pets.

As he became more familiar with his camera, Lartigue’s subjects and frames changed to reflect the moment: his subjects became car races in Auvergne, the bathers in Deauville and Biarritz, airplanes in Issy-les-Moulineaux and Buc, winter pastimes in Switzerland.

Grand Prix de l’ACF, Delage automobile, Dieppe Circuit 26 June 1912

In 1915 Lartique attended the Académie Jullian to study painting, which would become his lifelong profession. Photography, however, remained his great love. The expressive knowledge he learned via painting – but also his use of the various cameras over the years, in particular their technical limits – were the means he used to create his unique photographic style. Lartigue’s vision is of the Belle Époque, the bliss of happiness of French life before the First World War, an era also characterized by the Impressionists who painted in parallel with the innovation of the photographic medium. It was an aesthetic that gave a privileged view of bourgeois life in France in the early 1900s.

Véra et Arlette, Cannes, May 1927

*************

It was only in the 1960s, when he was almost 70, that his larger photographic archive became known to the general public via an exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1963 entitled “The Photographs of Jacque Henri Lartigue” curated by John Szarkowski, director of the Museum’s Department of Photography. Lartigue was “discovered” as if he were a child who had miraculously captured a passing world while documenting the beginnings of the new. It wasn’t a large show, 45 early photographs from the very beginning of Lartigue’s career, now iconic. Szarkowski described Lartigue’s photography as “the precursor of every interesting and lively creation made during the twentieth century”. Richard Avedon, after viewing Lartigue’s work at the MoMA in 1963 wrote to him that “It was one of the most moving and powerful experiences of my life. They are photographs that echo. I will never forget them. Seeing them was for me like reading Proust for the first time ”.

Lartigue remained no mere naive kid with a camera. If the 1963 MoMA photos are beautiful evocations of a lost world, the photographs that Lartigue took in the six decades of his working life constitute his enduring legacy. Kevin Moore’s monograph, Jacques Henri Lartigue: The Invention of an Artist (2004), argues for the sophistication and enduring quality of Lartigue’s mature work. According to Moore, Lartigue, with his ability to freeze the enduring moment in time, made the snapshot a work of art. That he did is a measure of his enduring worth as a photographer.

*************

In 1974, French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing commissioned Lartigue to produce his official portrait. In 1975 the Muséè des arts Décoratifs in Paris presented a large review of his photography, ‘Lartigue 8 x 80’, and in 1980 the Grand Palais in Paris exhibited a retrospective entitled ‘Bonjour Monsieur Lartigue‘ .

In 1979 Lartigue donated his entire work – negatives, original albums, diaries, cameras – to the French government which established the Association des Amis de Jacques Henri Lartigue, today called Donation Jacques Henri Lartigue, with the supervision of the Ministry of Culture. The function of the Donation is to promote Lartigue’s work.

Jacques-Henri Lartigue continued to photograph, paint and write until his death in September 1986, at the age of 92. He left over 100,000 photographs, 7,000 diary pages and 1,500 paintings.

Wittgenstein on Photography

“We regard the photograph, the picture on our wall, as the object itself (the man, the landscape, and so on) depicted there. This need not have been so. We could easily imagine people who did not have this relationship to pictures. Who, for example, would be repelled by photographs, because a face without color and even perhaps a face in reduced proportions struck them as inhuman.” —Ludwig Wittgenstein

Maybe I Need to Rethink This

The M8. I Had a Love/Hate With This Camera for Many Years

As you know, I’ve been, at best, ambivalent about Leica in the digital age. I’ve taken a lot of cheap shots at their digital cameras over the years, M digitals included. I’ve been skeptical that the Leica M film experience could be transposed to the digital age. Part of the problem is digital capture simply doesn’t lend itself to simplicity – it requires electronics and LCD screens and nested menus and all the afflatus that gives rise to digital bloat, and Leica isn’t immune to it in spite of their best intentions to keep things simple.

It seemed, at least in the beginning, that Leica’s continued emphasis on simplicity had become less a design ethos than a marketing slogan, or worse yet, a cynical way of attempting to paper over inferior product. It’s not like Leica, as anyone selling a widget, isn’t above self-serving puffery. Let’s face it: the M8, pleasing to look at and fondle like previous film Leicas, arrived with some serious issues: buggy electronics, color capture issues, battery problems, dismal ISO capabilities, a shutter that sounded like a construction-grade staple gun. The M9 fixed some of it, but I couldn’t help but think that Leica was over their heads in the digital age, where quality had less to do with traditional Leica hand-craftsmanship and more with technical expertise, technical expertise being the forte of large manufacturers like Nikon and Canon.

*************

And then there was the Leica ergonomic, the felt experience of operating one that was so seductive with their film M’s. The film M’s just feel right. Refined yet simple. No intercession of electronics to do things for you (before the M7 at least). Radically minimalist design, uncluttered viewfinder, big bright mechanical rangefinder. Simple wind-on, imperceptible shutter click, rewind. Advancing the film offered just enough throw and resistance to make the act pleasurable as its own experience. Many Leicaphiles carried our M’s around the house with us – why? because they stimulated that part of the lizard brain connected to the hand. Film M’s made you a gearhead.

I’m not sure that ergonomic simplicity transfers over to the digital M’s, or at least I was skeptical at best. While my M8 looked like an M it didn’t feel like one. Whatever magic they packed into the M4 was simply not there in the M8. Where the M4 felt fluidly effortless and simple, the M8 felt clunky and convoluted. Where the M4 shutter whispered, the M8 sounded like it was shooting high-velocity projectiles. Figuring out how to format a card or change ISO invariably devolved into multi-thumb fumbling of wheels, buttons, and menu options, all while your subject fleeing as if from a school shooter. Efficient it wasn’t.

But …. if your interest was traditional B&W photography, as opposed to digital hyper-realism, in spite of what sensor rankings and 100% cropping geeks declaimed, the M8’s output was astonishing. B&W from the M8 just had the look, a function of the CCD sensor and its increased IR sensitivity which produced thick, film-like B&W files. All you needed to do was add a bit of grain. I was willing to put up with the quirks – the random freeze-ups, the glacial boot-up times, the god-awful swack of the shutter – to get that B&W output. It was that good, a monochrome camera to rival the Monochrom.

*************

This is all prelude to the fact that I’m having to rethink my opinions these days [shock!]. I bought a used M240 a while ago, not expecting much, and found that I really liked it, as in really. Wanting a digital camera to compliment my aging GXR and my exasperating Sigma SD Quattro (another love/hate thing), I’d thought of the usual alternatives – an X100, X-Pro, D4s – and then decided against them. It was time to buy a digital M.

To make a long story short – I liked the M240 so much I splurged and bought the camera I’d always really wanted – the Monochrom, the original CCD version based on the M9 platform. Found a nice one with an updated, non-corrosive sensor. I’ve totally fallen in love. It’s a digital M4. It’s got the feel. Hell, it even looks just like a black chrome M4. As for output, I’m convinced there’s a roll of Ilford HP5 rated at 800 ISO hidden in there somewhere.

An M5 w/ HP5 @ 800 ISO, an M240 DNG Run Through Silver Efex … or a Leica Monochrom?

So, going forward I’ve decided to go all Steve Huff on you, amusing you with various posts about the Mono and the M240 and how they compare to an M5 with HP5. This weekend, I’m going out with the M5 and a 35mm VC loaded with HP5, the Mono and the M240 and see how they each render the same subject. If you’ll indulge my geekiness, I promise no 100% crops or duplicate shots of fence posts. I’ll try to keep shots of the wife and cats to a minimum.

Leica is F**king With Us Again

Leica Camera has announced a limited edition M10-P “Reporter” as a homage to press photographers.

The M10-P Reporter features a dark green design and Kevlar covering, a high-strength synthetic fiber used in ballistic-protective clothing. This Kevlar covering will gradually turn the same color as its top and base plates through exposure to sunlight, “developing its own patina, which means that each camera will become a unique signature of its owner.” Leica M10-P Reporter sells for $8,795.00 and is limited to 450 units. No word on whether there will be a subsequent Lenny Kravitz version.

My Question: is there a guy who sits at a desk in Wetzlar tasked with thinking up shit like this that will drive us crazy?

The Leica M10-P Reporter in pre-patina state

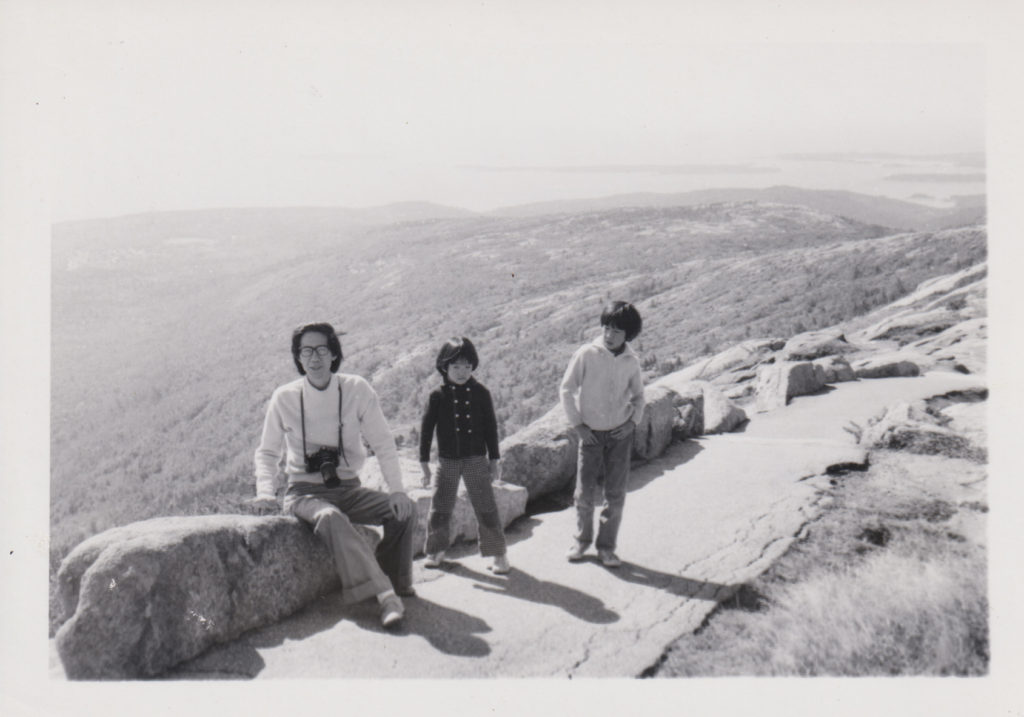

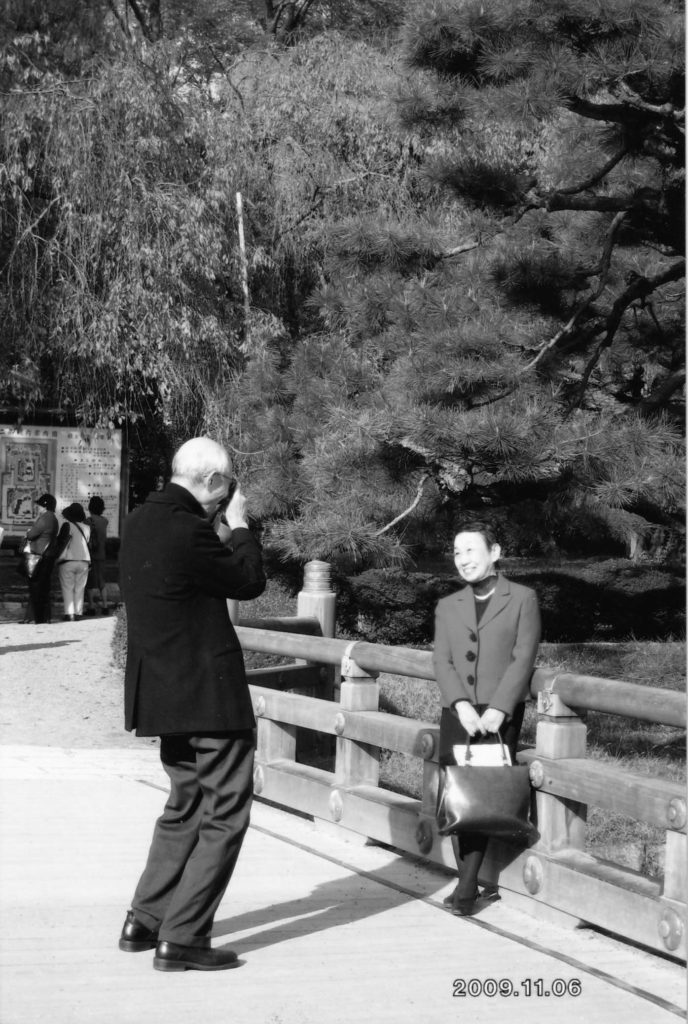

Memento Mori: Ohno Tsuneya, Oct 9, 1937 – Dec 23, 2017

By Shuya Ohno

[Editor’s Note: This was sent to me by reader Shuya Ohno as a beautifully designed PDF presentation. Unfortunately, I’m not sophisticated enough to publish the PDF as received, so I’ve reformatted it for publication. It’s a loving tribute from a son to a father and how that father passed his love of photography – and a Leica M3 – to his son.]

My father – Ohno Tsuneya – was born into a peaceful small town in the hilly countryside of Saitama prefecture, a few hours by train from Tokyo. His hometown, Chichibu, nestled among small mountains provided an ideal playground for a young mind to explore fields of wildflowers filled with insects, forests reverberating with cicadas all summer, and brooks and streams with nymphs, tadpoles, crayfish, and minnows. In town, he gathered with other schoolchildren on Sundays and spent his pocket change on candy so he could listen to the local kamishibai busker tell stories with his hand-painted pictures depicting fantastical illustrations of ghouls and heroes.

Like any boy during that time, he played baseball – that American import that’s also quintessentially Japanese. Like me, my father was slight in build, tall and lanky. Not athletic but loved to hike, ski, and explore. When the fever of war swept across the country, my father like all the young boys his age were indoctrinated at school to defend the motherland, and with their spindly arms taught to hold and wield bamboo poles as spears to poke at straw effigies of enemy soldiers.

As the youngest of four siblings, my father had freedom to play. His father, a local politician, was a man of airs and appetites, a connoisseur who raised renowned hunting dogs that he had imported from Scotland. All the filial duties and expectations to succeed fell on my uncle, my father’s elder brother who my father no doubt worshiped.

WWII and the devastation of the country left Japan with per capita income less than that of India at the time. Late in the war, Tokyo in a single firebombing raid saw over 100,000 civilians killed, over a million homeless. Food was scarce. My mother’s mother sold off kimonos to buy rice, and sewed the rice into blankets to smuggle from the countryside to Tokyo for family. My father’s mother had to smuggle rice from more rural areas back to Chichibu. After the war, Japan threw itself into the long arduous task of rebuilding the country and society. My grandfather Ohno Tetsu died in 1950, during the American occupation of Japan. He was 46 years old.

*************

My uncle Ohno Mitsuya sailed to the US to study journalism at the University of San Francisco. He never returned. Suffering from Marfan’s syndrome, he died presumably of a burst aortic aneurysm. He was only 23 years old. My father was still a teenager – and was now the only man of the house.

He came out to Tokyo to study at 9 years old, and eventually went on to study medicine at Jikei Medical University – the school he would later return to as a researcher and professor. He met my mother, Taniguchi Makiko when he was a student, bicycling across town to see her.

My mother was born on the first day of summer in 1940 in Tokyo, though her family hailed proudly from Kagoshima, the southern holdout of the last of the samurai. Her father Taniguchi Eizo served in the capital as an attorney for the City of Tokyo. During the war, her family fled to the countryside near Hiroshima after their house in Tokyo was firebombed. Eizo continued to work in Tokyo. On August 6th, 1945 my mother was 5 years old, playing when she and her mother saw a flash in the sky in the distance – it was the first atomic explosion and the end of the war. Eizo did his legal duty and served as a defense attorney during the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

Like my father’ father, Ohno Tetsu, my mother’s father Taniguchi Eizo died in 1950. He was 56 years old.

My father was 13, my mother was 10 years old when they lost their fathers. My mother’s mother, Emi, died after struggling with severe depression for eight years. My parents came of age without having a father in their lives.

*************

My father loved photography – the art, the activity, the ritual, the tools. One of the last times he and I shared an outing was a brisk February Sunday in 2004, a day before my 38th birthday. We spent the afternoon at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography to see a retrospective of Tanuma Takeyoshi.The exhibit spanned 60 years of Tanuma’s career, beginning with images of post-War children in Tokyo from 1949 that he took as a young apprenticing photojournalist.

In 1956, the Family of Man exhibition came to Tokyo. Tanuma was inspired by this exhibition and went to see it again and again. So did my father. The exhibition is still regarded as a grand undertaking, 503 photographs from 68 countries – its magnitude matched only by its own hubris and that of its curator, the photographer Edward Steichen.

However naïve it may seem today, the driving aspirations and ethos of the exhibit, to capture and encompass humanity in its multitudes as a single connected family, was situated firmly in the liberal ideology of its time, reflected in the contemporaneously articulated charter of the United Nations:

We the peoples of the United Nations determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war…to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and… to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom.

*************

The post-war Japanese intellectual of the late-Twentieth Century was an amalgam of times and cultures. Adorned with a black beret or a bucket hat, tucked into a turtleneck, the aficionado of culture and the cool connoisseur of consumer goods practiced as an amateur naturalist, a hobbyist polymath, and a citizen of the world. Simultaneously Modern and Romantic, the intellectual eccentric saw himself as hero, like a Sherlock Holmes – a Victorian avatar that still stubbornly abides in Japan.

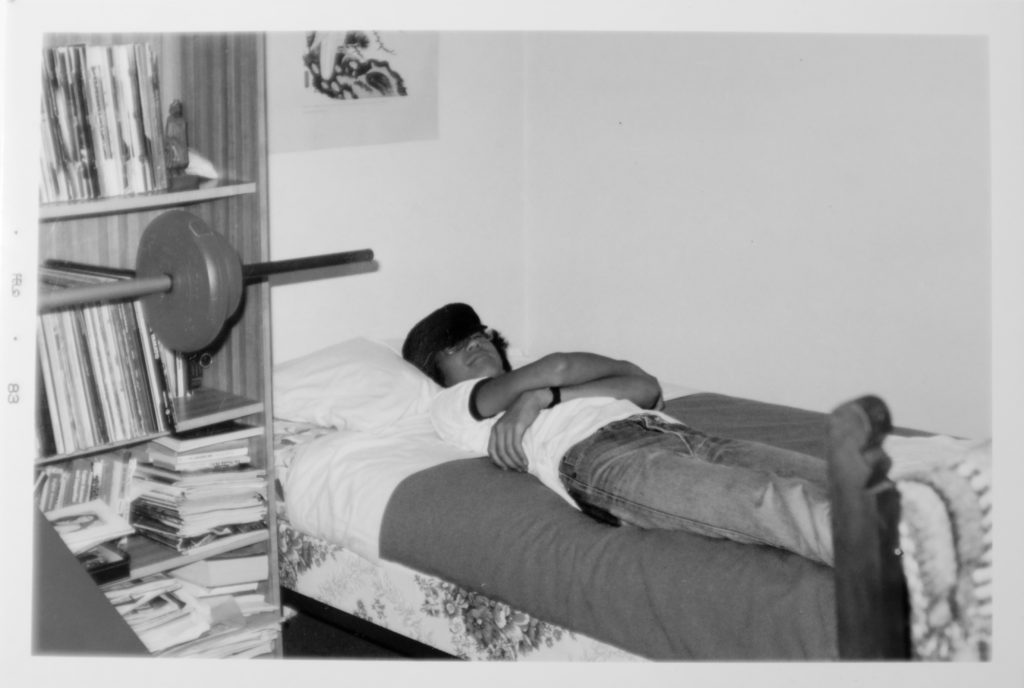

It is not surprising then that my father left us in the United States and returned to Japan. He had brought us, my mother and my brothers, Shinya and Michiyuki to the US when I was 6 years old. My parents remained a married couple – we were still a family – just separated by 13 time zones and 6,740 miles. He left when I was 14. I had worshiped him until then.

Throughout my high school days, I felt his absence, and filled it with rage. I was angry at myself for feeling angry toward my father – I felt like I was desecrating some sacred filial code. I drove my mother crazy, at times to tears. She deserved none of it. It took me into adulthood until I stopped following in his footsteps and abandoned science, until I worked feverishly making art, and then making social justice change that I felt relieved of my anger, forgiving my father and accepting and understanding him. He never saw it as abandonment, just a temporary necessity dictated by his work ethic. My mother eventually joined him after Michi graduated from Rutgers. Michi was perhaps the most American of us for having grown up in the US since he was 3 years old, but he too went to settle back in Tokyo.

*************

I inherited my father’s 1956 Leica M3 (#831611). It’s not that he bequeathed it to me. I claimed it a couple of days after he passed away. I like to believe he would have set it aside for me – but perhaps he meant to sell it. I didn’t know this M3 existed until I was rummaging through his cabinet of classic cameras, divvying up the collection between my brothers and myself. It was not a camera I had ever seen him use. He used a Nikormat while we all lived in the US. He gave that camera to my brother Shinya. My father used a black Leica M6 after that. But I knew what the M3 meant to him. We had years ago discussed its lineage and its reputation as the pinnacle of craft and industrialization, the greatest camera of the 20th century.

Industrialization and the availability of the easy point and shoot 35mm camera became a turning point for the modern world. Susan Sontag in her seminal essay, “Photography,” first published in the New York Review of Books in 1973 presaged my father’s relationship to his camera.

“The very activity of taking pictures is soothing,” she wrote, “and assuages general feelings of disorientation that are likely to be exacerbated by travel.” For my family, it was not travel but immigration in 1972 – jarring and alienating. Language proficiency, or rather its lack, always kept my father a little apart from interactions, a little behind in conversations. I could always see his desire to drop the bon mot, the jokes and puns he had in his head, if only he had mastery over English the way he had over Japanese. Instead, he had his camera. Sontag continued, “Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter.” It is a fine instrument for capturing and collecting moments but also a tool for defense.

Her essay is still incisive, perhaps more so with the advent of the cellphone. “People robbed of their past seem to make the most fervent picture-takers, at home and abroad. Everyone who lives in an industrialized society is obliged gradually to give up the past, but in certain countries, such as the United States and Japan, the break with the past has been particularly traumatic.” Migration only exacerbates this break.

For the last two years of his life, my father was bed-ridden in the hospital. He was intubated and then given a tracheotomy, taking his voice. By the end, he lost his desire to communicate, left his thick glasses by the bed and no longer cared if he could see.

I inherited from my father, not only his camera, but also his adulation for what he glimpsed in that Family of Man exhibit – a vision of humanity suffused with dignity and love for all people, an exaltation of the everyday, the celebration of the common person, and the democratization of art

Now I strive to take photographs that express my love for the world. And every time I pick up the M3, every time I press the shutter, it is a continuing conversation with my father. The viewfinder of this old camera is his eyes, as I ask him, “Do you see? Do you see?”

*************

“All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” – Susan Sontag.

The Canon VT – Canon’s Version of A Leica Trigger Winder With an M3 Attached

There’s no rhyme or reason when it comes to prices for film cameras, certainly when we’re talking about Leica and/ its alternatives. Case in point, the Leicavit-M rapid manual film advance winder which attaches to your Leica M to facilitate “rapid” winding of your film.Out the door you’ll pay $1400 for the winder. It’s an interesting accessory allowing the 50’s equivalent of ‘burst-mode’ shooting by dedicating your right hand to the shutter button while your left hand winds the film via the trigger lever located at the base of the camera body. Weird, but it works. Leica has been offering some variation on the trigger winder since the Leica III SCNOO winder first appeared in 1935.

*************

In 1956 Canon introduced the “Canon 5”, the V, trigger winder permanently attached. For a little more than the price of a new Leica Winder, I recently scored a beautiful black paint Canon V – Canon’s answer to the M3 – with almost new (“MINTY!) Canon 35mm 1.8 and matching Canon 50mm 1.8. The whole set. The V and the 50 are black paint, stripped, dechromed and repainted to spec by Sheudo in Japan, the 35 the black and chrome variant introduced with the V. The V in black paint 50 is a beauty, a stunning example of Canon’s minimalist rangefinder design ethos. My particular Canon V shows little to no evidence of usage, bright golden rangefinder patch, viewfinder clear and contrasty. The trigger winder works great. Both lenses are like new. It’s a lovely camera and two lens set-up, a perfect 1956 period piece highlighting the best Japanese camera technology of the era, all of it the equal of the now stratospherically priced Leitz offerings of the same era.

The introduction of the Leica M3 in 1954 presented an existential challenge to Canon/Nikon/Contax rangefinders. It was that revolutionary. Big, contrasty almost lifesize viewfinder (.91 magnification) big, bright rangefinder patch, parallax corrected for 50, 90 and 135mm focal lengths, its form factor an instant classic. In response, Nikon introduced the SP while Canon introduced the ‘original’ Canon VT, the “V” in August 1956 (not the be confused with all the other VT variants subsequently introduced by Canon, all of which didn’t possess the film advance knob of the original V). Canon produced it for only 10 months: April 1956 to February 1957. Its sales numbers were consequently low: 15,575. Unlike the M3, the V retained the Leica Thread mount. Canon launched it with three new LTM lenses: the improved 50mm f1.8, the new 50mm f1.2 and the 35mm f1.8.

The original V featured important rangefinder camera innovations: Most importantly, a rapid film wind trigger built into the camera base plate obviating the need to attach a Canon’ Rapid Winder’, a trigger winder for film advance, but also sporting a knob winder on the top plate that allowed film advance if necessary without the use of the trigger winder; a greatly improved viewfinder, described below; the improved shutter mechanism of the Canon IVSB2; a fully opening back for film loading, rather than the more difficult bottom loading of all previous Canons and the fiddly M3; replacement of the Canon flash rail with a compact PC outlet, compatible with many new electronic strobe flashes, and with a surrounding bayonet lock into which a new range of Canon flash units could be attached, compactly; and for the first time, a self-timer built into the camera body

Canon VT Viewfinder and Parallax Adjustment

The viewfinder of the Canon VT is nice, but not up to the M3’s lofty standards. It featured improved brightness and offered three viewing positions: the “35” position provided a full 35mm view, but without bright lines or parallax correction; – the “50” position gave a 70% of life-size view for the 50mm lens; – although not parallax corrected in the normal viewfinder, the Canon VT had a new feature in the accessory shoe. A pin in the center of the accessory shoe was raised and lowered according to the rangefinder focus. This pin linked to new V-type Canon accessory finders. The finders would raise and lower, moved by the pin, as the camera was focused, allowing them to correct automatically for parallax. This was an advanced feature unique to Canon.

*************

Canon 50mm f1.8 Lens 6 element, 4 group Planar design, 40mm filter

Canon, originally called Seiki-Kōgaku Kenkyusho (精機光学研究所), was formed in 1933 in Roppongi, Tokyo. The name meant “Precision Optical Instruments Laboratory”. Canon had a working relationship with Nippon Kōgaku (Nikon), who supplied lenses for the cameras which Canon manufactured. The Nikkor 5cm f/3.5 lens was commonly seen on the Hansa Kwanon (Canon), which also had its rangefinder manufactured by Nikon.

The Hansa Canon was launched in 1936. It was not until the late 1940s that Canon started to manufacture their own lenses. Initially, the lenses were labeled Serenar. This caused some confusion to customers as they were looking for a Precision Optical camera and a Serenar lens. In the early 1950s the company and branding changed to ‘Canon’.

The first Canon produced 50mm f/1.8 LTM (Type 1) was branded Serenar. It came in an all chrome configuration. This lens, originally sold with the “Leica copy” Canon II, III and IV, was patented in 1951 by Canon engineer Hiroshi Ito. It was patented in Germany and forced Leica to create the more complicated f2 Summicron design, which overall wasn’t better in performance than the Canon.

In April 1956, Canon introduced three new lenses to coincide with V: the new 35mm f1.8, a new Canon 50mm f1.2, and an updated Canon 50mm 1.8. The ‘Canon’ 50mm f1.8 was updated with new lightweight metal alloy and had black focusing and lens rings. It looked more modern than the full chrome version and it went better with the few black paint V’s you could special order from the factory, Canon did offer a full black paint version of the updated 50mm 1.8. You could buy the black paint lens/ body combo via special factory order. The black V body and 50mm full black lens remains one of the rarest of Canon rangefinder set-ups. So what if mine is a repaint. It’s as beautiful as an original and costs thousands less. Who gives a shit who painted it, some guy on the Canon assembly line or some passionate camera tech in Japan?

My Repainted Black Paint Canon 50mm 1.8 Rangefinder Lens. It’s a Beauty Even After 65 Years of Use.

*************

Canon 35mm f1.8 Lens 7 element, 4 group design, 40mm filter size.

Newly offered with the introduction of the V, the 35mm F1.8 had a light-weight aluminum alloy body with a satin chrome finish and a black aperture ring. It has a slow-twist barrel with full click-stops at 1.8, 2 up to 22. The Canon 35mm lens in 1956 made a great fit with the original V, as the camera had a bright viewfinder with a choice between 50mm and 35mm viewfinder positions without the need for an accessory finder.

Canon sold only 14,796 35mm 1.8’s before it was superseded by the 35mm f2, so it’s relatively rare. It’s very compact, more so than the Leitz 35mm 2.0 Summicron. Unlike the Summicron, you don’t need a hood as the glass is recessed in the Canon lens. It’s a traditional ’50s era film optic – not too contrasty, centers sharp, marginal edge softness at full aperture – much like the first version Summicron. Bright light will make the lens flare anyway because of the lens design – a hood isn’t going to help. Get one now; like the W-Nikkor 38mm 1.8 in LTM a few years ago, it’s going up in price daily and I suspect will be cost-prohibitive in the near future likethe W-Nikkor has recently become (I sold my almost perfect LTM W-Nikkor 35 1.8 about 5 years ago for $1800; today they’re going on Ebay for $3200 in average condition).

Latest Summicron, Zeiss 35 2.8, Canon, Leitz 40 f2. The Canon is a compact little lens

According to Dante Stella, 35/1.8 is one of Canon’s more underappreciated LTM lenses. Good sharpness without being too contrasty across the whole frame, smooth bokeh. These are often seen with cleaning marks, and they are getting harder to find. Mine, serial number 22321, is probably the cleanest copy I’ve ever run across. No cleaning marks, no haze, fungus, separation. The barrel is remarkably unworn. It’s clearly been taken care of.

My Canon 35mm 1.8, Circa 1956. Not repainted, but it’s a Beauty too. Together with the Black Paint 50 and the Black V, it Makes a Great Set.

Leicaphilia Guy Discovers Instagram

Walking Buddy, 1/21/21

As I’ve mentioned previously, in conjunction with my tentative health issues, I’m in the process of reviewing 50 years of photo output, getting things in some sense of order, etc. To that end I’ve decided to start an instagram feed for LEICAPHILIA. I’m intending to post on the feed fairly regularly, a mix of things, like above, just snatched with the phone from daily life and images from my archive as I turn them up.

Consider this an invitation to follow me – LEICAPHILIA. Ask your kids/grandkids about how to do so if you need help.

Silver Efex’s Kodak Film Simulations

Leica M240, 7Artisans 50mm f/1.1

I’ll admit it: I’m a sucker for Nik’s Silver Efex software. While Nik is long gone, having apparently been bought out by Google, their Silver Efex software lives on. It’s my go-to choice for converting digital DNG files to B&W ‘film’ capture; in addition to adding characteristic grain of a specific B&W emulsion, it overlays the film’s exposure curve to re-create the tonalities of the film capture. Is it perfect? No. As I’ve attempted to explain elsewhere, the fact that you’re starting with the linear exposure curve of a DNG file as opposed to a native film file with the exposure curve ‘baked in’ makes perfect emulation impossible. But it’s close, and most folks are easily fooled.

Below are the various emulations of the digital file above. There’s been no tweaking the files at all except to load them into Silver Efex and choose the film emulation. You can click on them and open them in a new window for larger jpegs. If nothing else, it’s interesting to see the various looks of the different Kodak film stocks, which I think Nik did a great job of simulating. My preferences: Plus-X for a clean tonality, TMAX 3200 for a grittier look. As for Tri-X, I never much liked it, preferring instead the better tonality and decreased contrast of Ilford HP5. Of course, Silver Efex gives you the option of tweaking grain and tonality after you’ve loaded the film emulation preset, but then you’re not emulating a given film but modifying it as you might do with various developing choices, and that’s a rabbit hole I’m incapable of going down.

Panatomic – X, ISO 32

TMAX 100, ISO 100

Plus-X, ISO 125

TMAX 400, ISO 400

Tri-X, ISO 400

TMAX 3200, ISO 3200

The Cult of Leica

By Anthony Lane, New Yorker Magazine, September 24, 2007

Fifty miles north of Frankfurt lies the small German town of Solms. Turn off the main thoroughfare and you find yourself driving down tranquil suburban streets, with detached houses set back from the road, and, on a warm morning in late August, not a soul in sight. By the time you reach Oskar-Barnack-Strasse, the town has almost petered out; just before the railway line, however, there is a clutch of industrial buildings, with a red dot on the sign outside. As far as fanfare is concerned, that’s about it. But here is the place to go, if you want to find the most beautiful mechanical objects in the world.

There have been Leica cameras since 1925, when the Leica I was introduced at a trade fair in Leipzig. From then on, as the camera has evolved over eight decades, generations of users have turned to it in their hour of need, or their millisecond of inspiration. Aleksandr Rodchenko, André Kertész, Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, Robert Frank, William Klein, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Sebastião Salgado: these are some of the major-league names that are associated with the Leica brand—or, in the case of Cartier-Bresson, stuck to it with everlasting glue.

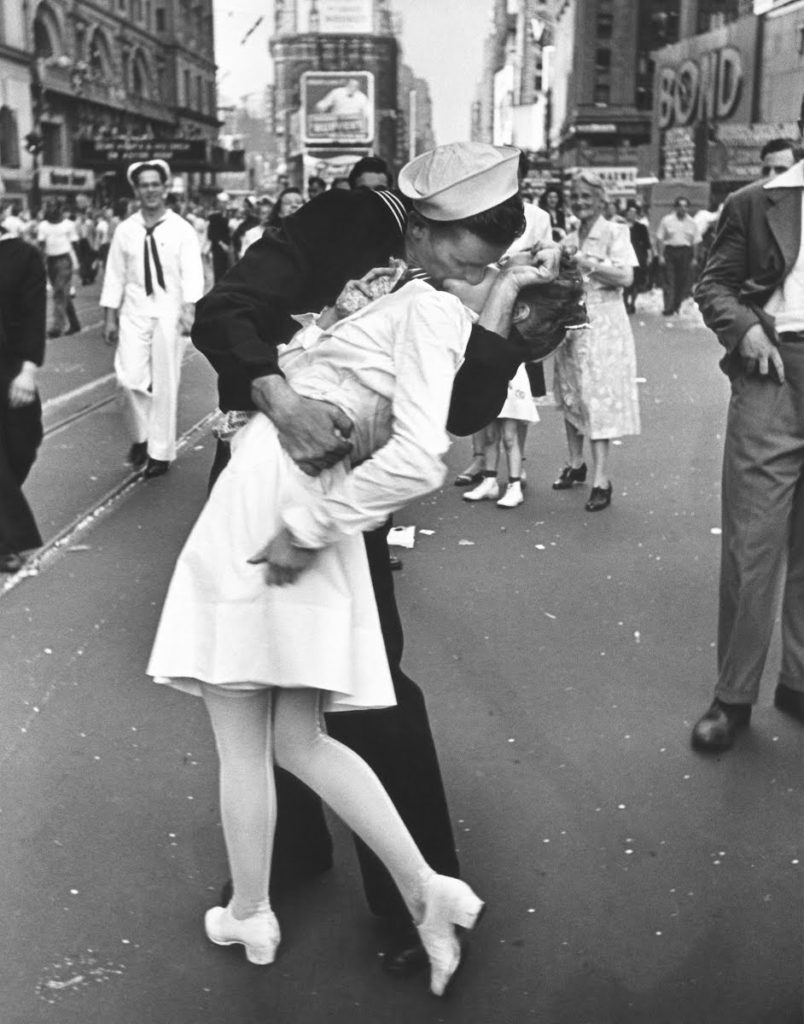

Even if you don’t follow photography, your mind’s eye will still be full of Leica photographs. The famous head shot of Che Guevara, reproduced on millions of rebellious T-shirts and student walls: that was taken on a Leica with a portrait lens—a short telephoto of 90 mm.—by Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez, better known as Korda, in 1960. How about the pearl-gray smile-cum-kiss reflected in the wing mirror of a car, taken by Elliott Erwitt in 1955? Leica again, as is the even more celebrated smooch caught in Times Square on V-J Day, 1945—a sailor craned over a nurse, bending her backward, her hand raised against his chest in polite half-protestation. The man behind the camera was Alfred Eisenstaedt, of Life magazine, who recalled:

I was running ahead of him with my Leica, looking back over my shoulder. But none of the pictures that were possible pleased me. Then suddenly, in a flash, I saw something white being grabbed. I turned around and clicked.

He took four pictures, and that was that. “It was done within a few seconds,” he said. All you need to know about the Leica is present in those seconds. The photographer was on the run, so whatever he was carrying had to be light and trim enough not to be a drag. He swivelled and fired in one motion, like the Sundance Kid. And everything happened as quickly for him as it did for the startled nurse, with all the components—the angles, the surrounding throng, the shining white of her dress and the kisser’s cap—falling into position. Times Square was the arena of uncontrolled joy; the job of the artist was to bring it under control, and the task of his camera was to bring life—or, at least, an improved version of it, graced with order and impact—to the readers of Life.

*************

Still, why should one lump of metal and glass be better at fulfilling that duty than any other? Would Eisenstaedt really have been worse off, or failed to hit the target, with another sort of camera? These days, Leica makes digital compacts and a beefy S.L.R., or single-lens reflex, called the R9, but for more than fifty years the pride of the company has been the M series of 35-mm. range-finder cameras—durable, companionable, costly, and basically unchanging, like a spouse. There are three current models, one of which, the MP, will set you back a throat-drying four thousand dollars or so; having stood outside dustless factory rooms, in Solms, and watched women in white coats and protective hairnets carefully applying black paint, with a slender brush, to the rim of every lens, I can tell you exactly where your money goes. Mind you, for four grand you don’t even get a lens—just the MP body. It sits there like a gum without a tooth until you add a lens, the cheapest being available for just under a thousand dollars. (Five and a half thousand will buy you a 50-mm. f/1, the widest lens on the market; for anybody wanting to shoot pictures by candlelight, there’s your answer.) If you simply want to take a nice photograph of your children, though, what’s wrong with a Canon PowerShot? Yours online for just over two hundred bucks, the PowerShot SD1000 will also zoom, focus for you, set the exposure for you, and advance the frame automatically for you, none of which the MP, like some sniffing aristocrat, will deign to do. To make the contest even starker, the SD1000 is a digital camera, fizzing with megapixels, whereas the Leica still stores images on that frail, combustible material known as film. Short of telling the kids to hold still while you copy them onto parchment, how much further out of touch could you be?

To non-photographers, Leica, more than any other manufacturer, is a legend with a hint of scam: suckers paying through the nose for a name, in a doomed attempt to crank up the credibility of a picture they were going to take anyway, just as weekend golfers splash out on a Callaway Big Bertha in a bid to convince themselves that, with a little more whippiness in their shaft, they will swell into Tiger Woods. To unrepentant aesthetes, on the other hand, there is something demeaning in the idea of Leica. Talent will out, they say, whatever the tools that lie to hand, and in a sense they are right: Woods would destroy us with a single rusty five-iron found at the back of a garage, and Cartier-Bresson could have picked up a Box Brownie and done more with a roll of film—summoning his usual miracles of poise and surprise—than the rest of us would manage with a lifetime of Leicas. Yet the man himself was quite clear on the matter:

I have never abandoned the Leica, anything different that I have tried has always brought me back to it. I am not saying this is the case for others. But as far as I am concerned it is the camera. It literally constitutes the optical extension of my eye.

Asked how he thought of the Leica, Cartier-Bresson said that it felt like “a big warm kiss, like a shot from a revolver, and like the psychoanalyst’s couch.” At this point, five thousand dollars begins to look like a bargain.

*************

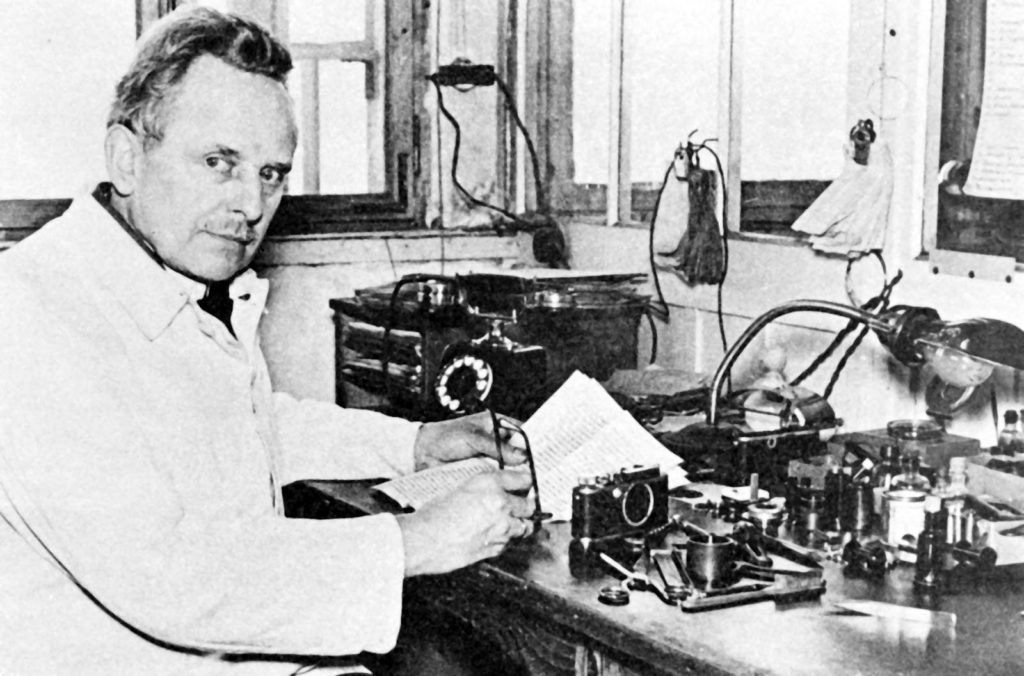

Oscar Barnack at his Desk

Many reasons have been adduced for the rise of the Leica. There is the hectic progress of the illustrated press, avid for photographs to fill its columns; there is the increased mobility, spending power, and leisure time of the middle classes, who wished to preserve a record of these novel blessings, if not for posterity, then at least for show. Yet the great inventions, more often than not, are triggered less by vast historical movements than by the pressures of individual chance—or, in Leica’s case, by asthma. Every Leica employee who drives down Oskar-Barnack-Strasse is reminded of corporate glory, for it was Barnack, a former engineer at Carl Zeiss, the famous lens-makers in Jena, who designed the Leica I. He was an amateur photographer, and the camera had first occurred to him, as if in a vision, in 1905, twenty years before it actually went on sale:

Back then I took pictures using a camera that took 13 by 18 plates, with six double-plate holders and a large leather case similar to a salesman’s sample case. This was quite a load to haul around when I set off each Sunday through the Thüringer Wald. While I struggled up the hillsides (bearing in mind that I suffer from asthma) an idea came to me. Couldn’t this be done differently?

Five years later, Barnack was invited to work for Ernst Leitz, a rival optical company, in Wetzlar. (The company stayed there until 1988, when it was sold, and the camera division, renamed Leica, shifted to Solms, fifteen minutes away.) By 1913-14, he had developed what became known as the ur-Leica: a tough, squat rectangular metal box, not much bigger than a spectacles case, with rounded corners and a retractable brass lens. You could tuck it into a jacket pocket, wander around the Thuringer woods all weekend, and never gasp for breath. The extraordinary fact is that, if you were to place it next to today’s Leica MP, the similarities would far outweigh the differences; stand a young man beside his own great-grandfather and you get the same effect.

Barnack took a picture on August 2, 1914, using his new device. Reproduced in Alessandro Pasi’s comprehensive study, “Leica: Witness to a Century” (2004), it shows a helmeted soldier turning away from a column on which he has just plastered the imperial order for mobilization. This was the first hint of the role that would fall to Leicas above all other cameras: to be there in history’s face. Not until the end of hostilities did Barnack resume work on the Leica, as it came to be called. (His own choice of name was Lilliput, but wiser counsels prevailed.) Whenever you buy a 35-mm. camera, you pay homage to Barnack, for it was his handheld invention that popularized the 24-mm.-by-36-mm. negative—a perfect ratio of 2:3—adapted from cine film. According to company lore, he held a strip of the new film between his hands and stretched his arms wide, the resulting length being just enough to contain thirty-six frames—the standard number of images, ever since, on a roll of 35-mm. film. Well, maybe. Does this mean that, if Barnack had been more of an ape, we might have got forty?

*************

When the Leica I made its eventual début, in 1925, it caused consternation. In the words of one Leica historian, quoted by Pasi, “To many of the old photographers it looked like a toy designed for a lady’s handbag.” Over the next seven years, however, nearly sixty thousand Leica I’s were sold. That’s a lot of handbags. The shutter speeds on the new camera ran up to one five-hundredth of a second, and the aperture opened wide to f/3.5. In 1932, the Leica II arrived, equipped with a range finder for more accurate focussing. I used one the other day—a mid-thirties model, although production lasted until 1948. Everything still ran sweetly, including the knurled knob with which you wind on from frame to frame, and the simplicity of the design made the Leica an infinitely more friendly proposition, for the novice, than one of the digital monsters from Nikon and Canon. Those need an instruction manual only slightly smaller than the Old Testament, whereas the Leica II sat in my palms like a puppy, begging to be taken out on the streets.

That is how it struck not only the public but also those for whom photography was a living, or an ecstatic pursuit. A German named Paul Wolff acquired a Leica in 1926 and became a high priest to the brand, winning many converts with his 1934 book “My Experiences with the Leica.” His compatriot Ilsa Bing, born to a Jewish family in Frankfurt, was dubbed “the Queen of the Leica” after an exhibit in 1931. She had bought the camera in 1929, and what is remarkable, as one scrolls through a roster of her peers, is how quickly, and infectiously, the Leica habit caught on. Whenever I pick up a book of photographs, I check the chronology at the back. From a monograph by the Hungarian André Kertész, the most wistful and tactful of photographers: “1928—Purchases first Leica.” From the catalogue of the 1998 Aleksandr Rodchenko show at moma: “1928, November 25—Stepanova’s diary records Rodchenko’s purchase of a Leica for 350 rubles.” And on it goes.

Ilsa Bing

The Russians were among the first and fiercest devotees, and anyone who craves the Leica as a pure emblem of capitalist desire—what Marx would call commodity fetishism—may also like to reflect on its status, to men like Rodchenko, as a weapon in the revolutionary struggle. Never a man to be tied down (he was also a painter, sculptor, and master of collage), he nonetheless believed that “only the camera is capable of reflecting contemporary life,” and he went on the attack, craning up at buildings and down from roofs, tipping his Leica at flights of steps and street parades, upending the world as if all its old complacencies could be shaken out of the bottom like dust. There is a gorgeous shot from 1934 entitled “Girl with a Leica,” in which his subject perches politely on a bench that arrows diagonally, and most impolitely, from lower left to upper right. She wears a soft white beret and dress, and her gaze is blank and misty, but thrown over the scene, like a net, is the shadow of a window grille—modernist geometry at war with reactionary decorum. The object she clasps in her lap, its strap drawn tightly over her shoulder, is of the same make as the one that created the picture.

When it came to off-centeredness, Rodchenko’s fellow-Russian Ilya Ehrenburg went one better. “A camera is clumsy and crude. It meddles insolently in other people’s affairs,” he wrote in 1932. “Ours is a guileful age. Following man’s example, things have also learned to dissemble. For many months I roamed Paris with a little camera. People would sometimes wonder: why was I taking pictures of a fence or a road? They didn’t know that I was taking pictures of them.” Ehrenburg had solved the problem of meddling by buying an accessory: “The Leica has a lateral viewfinder. It’s constructed like a periscope. I was photographing at 90 degrees.” The Paris that emerged—poor, grimy, and unposed—was a moral rebuke to the myth of bohemian chic.

*************

You can still buy a right-angled viewfinder for a new Leica, if you’re too shy or sneaky to confront your subjects head-on, although the basic thrust of Leica technique has been to insist that no extra subterfuge is required: the camera can hide itself. If I had to fix the source of that reticence, I would point to Marseilles in 1932. It was then that Cartier-Bresson, an aimless young Frenchman from a wealthy family, bought his first Leica. He proceeded to grow into the best-known photographer of the twentieth century, in spite (or, as he would argue, because) of his ability to walk down a street not merely unrecognized but unnoticed. He began as a painter, and continued to draw throughout his life, but his hand was most comfortable with a camera.

When I spoke to his widow, Martine Franck—the president of the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, in Paris, and herself a distinguished photographer—she said that her husband in action with his Leica “was like a dancer.” This feline unobtrusiveness led him all over the world and made him seem at home wherever he paused; one trip to Asia lasted three years, ending in 1950, and produced eight hundred and fifty rolls of film. His breakthrough collection, published two years later, was called “The Decisive Moment,” and he sought endless analogies for the sensation that was engendered by the press of a shutter. The most common of these was hunting: “The photographer must lie in wait, watching out for his prey, and have a presentiment of what is about to happen.”

There, if anywhere, is the Leica motto: watch and wait. If you were a predator, the moment—not just for Cartier-Bresson, but for all photographers—became that much more decisive in 1954. “Clairvoyance” means “clear sight,” and when Leica launched the M3 that year, the clarity was a coup de foudre; even now, when you look through a used M3, the world before you is brighter and crisper than seems feasible. You half expect to feel the crunch of autumn leaves beneath your feet. A Leica viewfinder resembles no other, because of the frame lines: thin white strips, parallel to each side of the frame, which show you the borders of the photograph that you are set to take—not merely the lie of the land within the shot, but also what is happening, or about to happen, just outside. This is a matter of millimetres, but to Leica fans it is sacred, because it allows them to plan and imagine a photograph as an act of storytelling—an instant grabbed at will from a continuum. If you want a slice of life, why not see the loaf?

*************

The M3 had everything, although by the standards of today it had practically nothing. You focussed manually, of course, and there was nothing to help you calculate the exposure; either you carried a separate light meter, or you clipped one awkwardly to the top of the camera, or, if you were cool, you guessed. Cartier-Bresson was cool. Martine Franck is still cool: “I think I know my light by now,” she told me. She continues to use her M3: “I’ve never held a camera so beautiful. It fits the hand so well.” Even for people who know nothing of Cartier-Bresson, and for whom 1954 is as long ago as Pompeii, something about the M3 clicks into place: last year, when eBay and Stuff magazine, in the U.K., took it upon themselves to nominate “the top gadget of all time,” the Game Boy came fifth, the Sony Walkman third, and the iPod second. First place went to an old camera that doesn’t even need a battery. If the Queen subscribes to Stuff, she will have nodded in approval, having owned an M3 since 1958. Her Majesty is so wedded to her Leica that she was once shown on a postage stamp holding it at the ready.

It’s no insult to call the M3 a gadget. Such beauty as it possesses flows from its scorn for the superfluous; as any Bauhaus designer could tell you, form follows function. The M series is the backbone of Leica; we are now at the M8 (which at first glance is barely distinguishable from the M3), and, with a couple of exceptions, every intervening camera has been a classic. Richard Kalvar, who rose to become president of the Magnum photographic agency during the nineties, remembers hearing the words of a Leica fan: “I know I’m using the best, and I don’t have to think about it anymore.” Kalvar bought an M4 and never looked back: “It’s almost a part of me,” he says. Ralph Gibson, whose photographs offer an unblinking survey of the textures that surround us, from skin to stone, bought his first Leica, an M2 (which, confusingly, postdated the M3), in 1961. It cost him three hundred dollars, which, considering that he was earning a hundred a week, was quite an outlay, but his loyalty is undimmed. “More great photographs have been made with a Leica and a 50-mm. lens than with any other combination in the history of photography,” Gibson said to me. He advised Leica beginners to use nothing except that standard lens for two or three years, so as to ease themselves into the swing of the thing: “What you learn you can then apply to all the other lengths.

One could argue that, since the nineteen-fifties and sixties, the sense of Europe as the spiritual hearth of Leica, with the Paris of Kertész and Cartier-Bresson glowing at its core, has been complemented, if not superseded, by America’s attraction to the brand. The Russian love of the angular had exploited the camera’s portability (you try bending over a window ledge with a plate camera); the French had perfected the art of reportage, netting experience on the wing; but the Leicas that conquered America—the M3, the M4, and later the M6, with built-in metering and the round red Leica logo on the front—were wielded with fresh appetite, biting at the world and slicing it off in unexpected chunks. Lee Friedlander, photographing a child in New York, in 1963, thought nothing of bringing the camera down to the boy’s eye level, and thus semi-decapitating the grownups who stood beside him. (All kids dream of that sometime.) Men and women were reflected in storefront windows, or obscured by street signs; many of the photographs shimmered on the brink of a mistake. “With a camera like that,” Friedlander has said of the Leica, “you don’t believe that you’re in the masterpiece business. It’s enough to be able to peck at the world.” One shot of his, from 1969, traps an entire landscape of feeling—a boundless American sky, salted with high clouds, plus Friedlander’s wife, Maria, with her lightly smiling face—inside the cab of a single truck, layering what we see through the side window with what is reflected in it. I know of long novels that tell you less.

Before Friedlander came Robert Frank, born in Switzerland; only someone from a mountainous country, perhaps, could come here and view the United States as a flat and tragic plain. “The Americans” (1958), the record of his travels with a Leica, was mostly haze, shade, and grain, stacked with human features resigned to their fate. No artist had ever studied a men’s room in such detail before, with everything from the mop to the hand dryer immortalized in the wide embrace of the lens; Jack Kerouac, who wrote the introduction to the book, lauded the result, taken in Memphis, Tennessee, as “the loneliest picture ever made, the urinals that women never see, the shoeshine going on in sad eternity.” Then, there was Garry Winogrand, the least exhaustible of all photographers. Frank’s eighty-three images may have been chosen from five hundred rolls of film, but when Winogrand died, in 1984, at the age of fifty-six, he left behind more than two and a half thousand rolls of film that hadn’t even been developed. He leavened the wistfulness of Frank with a documentary bluntness and a grinning wit, incessantly tilting his Leica to throw a scene off-balance and seek a new dynamic. His picture of a disabled man in Los Angeles, in 1969, could have been fuelled by pathos alone, or by political rage at an indifferent society, but Winogrand cannot stop tracking that society in its comic range; that is why we get not just the wheelchair and the begging bowl but also a trio of short-skirted girls, bunched together like a backup group, strolling through the Vs of shadow and sunlight, and a portly matron planted at the right of the frame—a stolid import from another age.

*************

Garry Winogrand’s M4

I recently found a picture of Winogrand’s M4. The metal is not just rubbed but visibly worn down beside the wind-on lever; you have to shoot a heck of a lot of photographs on a Leica before that happens. Still, his M4 is in mint condition compared with the M2 owned by Bruce Davidson, the American photographer whose work constitutes, among other things, an invaluable record of the civil-rights movement. And even his M2, pitted and peeled like the bark of a tree, is pristine compared with the Leica I saw in the display case at the Leica factory in Solms. That model had been in the Hindenburg when it went up in flames in New Jersey in 1937. The heat was so intense that the front of the lenses melted. So now you know: Leica engineers test their product to the limits, and they will customize it for you if you are planning a trip to the Arctic, but when you really want to trash your precious camera you need an exploding airship.

If you pick up an M-series Leica, two things are immediately apparent. First, the density: the object sits neatly but not lightly in the hand, and a full day’s shooting, with the camera continually hefted to the eye, leaves you with a faint but discernible case of wrist ache. Second, there is no lump. Most of the smarter, costlier cameras in the world are S.L.R.s, with a lumpy prism on top. Light enters through the lens, strikes an angled mirror, and bounces upward to the prism, where it strikes one surface after another, like a ball in a squash court, before exiting through the viewfinder. You see what your lens sees, and you focus accordingly. This happy state of affairs does not endure. As you take a picture, the mirror flips up out of the light path. The image, now unobstructed, reaches straight to the rear of the camera and, as the shutter opens, burns into the emulsion of the film—or, these days, registers on a digital sensor. With every flip, however, comes a flip side: the mirror shuts off access to the prism, meaning that, at the instant of release, your vision is blocked, and you are left gazing at the dark.

To most of us, this is not a problem. The instant passes, the mirror flips back down, and lo, there is light. For some photographers, though, the impediment is agony: of all the times to deny us the right to look at our subject, S.L.R.s have to pick this one? “Visualus interruptus,” Ralph Gibson calls it, and here is where the Leica M series plays its ace. The Leica is lumpless, with a flat top built from a single piece of brass. It has no prism, because it focusses with a range finder—situated above the lens. And it has no mirror inside, and therefore no clunk as the mirror swings. When you take a picture with an S.L.R., there is a distinctive sound, somewhere between a clatter and a thump; I worship my beat-up Nikon FE, but there is no denying that every snap reminds me of a cow kicking over a milk pail. With a Leica, all you hear is the shutter, which is the quietest on the market. The result—and this may be the most seductive reason for the Leica cult—is that a photograph sounds like a kiss.

From the start, this tinge of diplomatic subtlety has shaded our view of the Leica, not always helpfully. The M-series range finder feels made for the finesse and formality of black-and-white—yet consider the oeuvre of William Eggleston, whose unabashed use of color has delivered, through Leica lenses, a lesson in everyday American surrealism, which, like David Lynch movies, blooms almost painfully bright. Again, the Leica, with its range of wide-aperture lenses, is the camera for natural light, and thus inimical to flash, yet Lee Friedlander conjured a series of plainly flashlit nudes, in the nineteen-seventies, which finds tenderness and dignity in the brazen. Lastly, a Leica is, before anything else, a 35-mm. camera. Barnack shaped the Leica I around a strip of film, and the essential mission of the brand since then has been to guarantee that a single chemical event—the action of light on a photosensitive surface—passes off as smoothly as possible. Picture the scene, then, in Cologne, in the fall of 2006. At Photokina, the biennial fair of the world’s photographic trade, Leica made an announcement: it was time, we were told, for the M8. The M series was going digital. It was like Dylan going electric.

In a way, this had to happen. The tide of our lives is surging in a digital direction. My complete childhood is distilled into a couple of photograph albums, with the highlights, whether of achievement or embarrassment, captured in no more than a dozen talismanic stills, now faded and curling at the edges. Yet our own children go on one school trip and return with a hundred images stashed on a memory card: will that enhance or dilute their later remembrance of themselves? Will our experience be any the richer for being so retrievable, or could an individual history risk being wiped, or corrupted, as briskly as a memory card? Garry Winogrand might have felt relieved to secure those thousands of images on a hard drive, rather than on frangible film, although it could be that the taking of a photograph meant more to him than the printed result. The jury is out, but one thing is for sure: film is dwindling into a minority taste, upheld largely by professionals and stubborn, nostalgic perfectionists. Nikon now offers twenty-two digital models, for instance, while the “wide array of SLR film cameras,” as promised on its Web site, numbers precisely two.

Lee knows what is at stake, being a Leica-lover of long standing. Asked about the difference between using his product and an ordinary camera, he replied: “One is driving a Morgan four-by-four down a country lane, the other one is getting in a Mercedes station wagon and going a hundred miles an hour.” The problem is that, for photographers as for drivers, the most pressing criterion these days is speed, and anything more sluggish than the latest Mercedes—anything, likewise, not tricked out with luxurious extras—belongs to the realm of heritage. There is an astonishing industry in used Leicas, with clubs and forums debating such vital areas of contention as the strap lugs introduced in 1933. There are collectors who buy a Leica and never take it out of the box; others who discreetly amass the special models forged for the Luftwaffe. Ralph Gibson once went to a meeting of the Leica Historical Society of America and, he claims, listened to a retired Marine Corps general give a scholarly paper on certain discrepancies in the serial numbers of Leica lens caps. “Leicaweenies,” Gibson calls such addicts, and they are part of the charming, unbreakable spell that the name continues to cast, as well as a tribute to the working longevity of the cameras. By an unfortunate irony, the abiding virtues of the secondhand slow down the sales of the new: why buy an M8 when you can buy an M3 for a quarter of the price and wind up with comparable results? The economic equation is perverse: “I believe that for every euro we make in sales, the market does four euros of business,” Lee said.

*************

I have always wanted a Leica, ever since I saw an Edward Weston photograph of Henry Fonda, his noble profile etched against the sky, a cigarette between two fingers, and a Leica resting against the corduroy of his jacket. I have used a variety of cultish cameras, all of them secondhand at least, and all based on a negative larger than 35 mm.: a Bronica, a Mamiya 7, and the celebrated twin-lens Rolleiflex, which needs to be cupped at waist height. (“If the good Lord had wanted us to take photographs with a 6 by 6, he would have put eyes in our belly,” a scornful Cartier-Bresson said.) But I have never used a Leica. Now I own one: a small, dapper digital compact called the D-Lux 3. It has a fine lens, and its grace note is a retro leather case that makes me feel less like Henry Fonda and more like a hiker named Helmut, striding around the Black Forest in long socks and a dark-green hat with a feather in it; but a D-Lux 3 is not an M8. For one thing, it doesn’t have a proper viewfinder. For another, it costs close to six hundred dollars—the upper limit of my budget, but laughably cheap to anyone versed in the M series. So, to discover what I was missing, I rented an M8 and a 50-mm lens for four hours, from a Leica dealer, and went to work.

If you can conquer the slight queasiness that comes from walking about with seven thousand dollars’ worth of machinery hanging around your neck, an afternoon with the M8 is a dangerously pleasant groove to get into. I can understand that, were you a sports photographer, perched far away from the action, or a paparazzo, fighting to squeeze off twenty consecutive frames of Britney Spears falling down outside a night club, this would not be your tool of choice, but for more patient mortals it feels very usable indeed. This is not just a question of ergonomics, or of the diamond-like sharpness of the lens. Rather, it has to do with the old, bewildering Leica trick: the illusion, fostered by a mere machine, that the world out there is asking to be looked at—to be caught and consumed while it is fresh, like a trout. Ever since my teens, as one substandard print after another glimmered into view in the developing tray, under the brothel-red gloom of the darkroom, my own attempts at photography have meant a lurch of expectation and disappointment. Now, with an M8 in my possession, the shame gave way to a thrill. At one point, I stood outside a bookstore and, in a bid to test the exposure, focussed on a pair of browsers standing within, under an “Antiquarian” sign at the end of a long shelf. Suddenly, a pale blur entered the frame lines. I panicked, and pressed the shutter: kiss.

On the digital playback, I inspected the evidence. The blur had been an old lady, and she had emerged as a phantom—the complete antiquarian, with glowing white hair and a hint of spectacles. It wasn’t a good photograph, more of a still from “Ghostbusters,” but it was funnier and punchier than anything I had taken before, and I could only have grabbed it with a Leica. (And only with an M. By the time the D-Lux 3 had fired up and focussed, the lady would have floated halfway down the street.) So the rumors were true: buy this camera, and accidents will happen. I remembered what Cartier-Bresson once said about turning from painting to photography: “the adventurer in me felt obliged to testify with a quicker instrument than a brush to the scars of the world.” That is what links him to the Leicaweenies, and Oskar Barnack to the advent of the M8, and Russian revolutionaries to flashlit American nudes: the simple, undying wish to look at the scars.

Alexander Rodchenko, Leica Lover

The photo above – Devushka s Leikoi – was taken by the constructivist painter/ designer and photographer Alexander Rodchenko with his Leica I. The image is of his assistant and lover Evgenlia Lemberg relaxing in Gorky Park circa 1934. Shortly thereafter Evgenlia was killed in a train accident – a trip that Rodchenko was supposed to take with her but postponed at the last minute. Rodchenko claimed he dreamt about Evgenlia for years after her death. Apparently, this didn’t stop him from also banging her younger sister Regina, who died of gangrene in 1938. That’s her, below, with her Leica. All of this happened while Rodchenko was “happily” married to artist Varvara Stepanova in 1922, with whom he would remain until his death in 1956.

Rodchenko reportedly purchased the first Leica in Russia and was so strongly associated with the camera that a chapter in his biography is titled simply “Leica Photography.”

As a key figure of the Russian modernist movement, Rodchenko helped redefine three key visual genres of modernism: photography, painting and graphic design. In the field of photography, he established unprecedented compositional paradigms, which in many ways still define the entire notion of modern photographic art. In his paintings, the artist further explored and expanded the essential vocabulary of an abstract composition. His series of purely abstract proto-monochrome paintings were influential to artists such as Ad Reinhardt and the Minimalists of the 1960s. Rodchenko’s involvement with the Bolshevik cause further propelled the appreciation of his art in the leftist circles of the American avant-garde.

Rodchenko Checking Out the Ladies with His Leica I

With Wife Varvara Stepanova

A Trinocular Vision

“When it comes to organizing the world into a picture, the photographer has little to go on…[his] only constraining form is his frame. Inside those four edges there are no structural traditions, only space.” — Ben Lifson

Robert Capa famously said that if your pictures weren’t good enough you weren’t close enough. I always thought that was wrong. Sometimes you can miss a picture by being too close.

Aesthetics is a question of where you place the frame. As psychologist Rudolf Arheim notes, the visual world surrounds us as an unbroken space, subdivided conceptually but without limits. Photography is the practice of isolating a portion of that whole, always with the understanding that the world continues beyond the frame’s borders. Part of what gives a photo meaning is the larger context within which it resides; sometimes that context is implied, sometimes it’s expressly pictured. Sometimes the subject is found within the frame while its context lies out of frame. Other times the photo is the dynamic of context and form within the frame; for this you need distance. Robert Capa would be an example of the former; Henri Cartier-Bresson would be an example of the latter. There’s room for both in photo aesthetics.

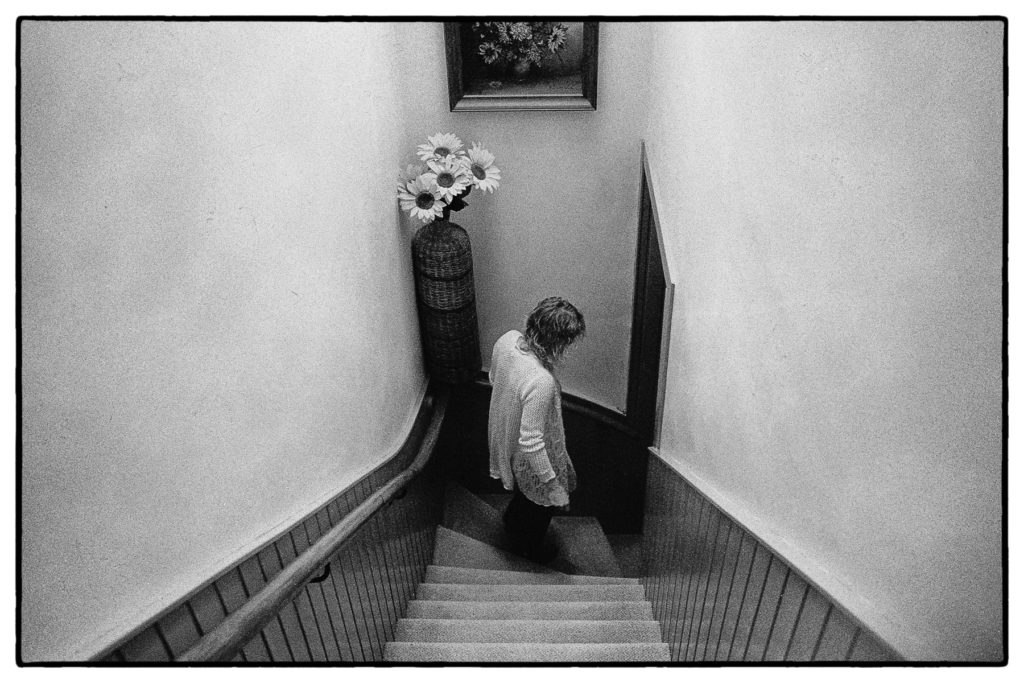

I say all of this because I’ve been admiring the photography of Erik van Straten, a Dutch amateur photographer [‘amateur’ in the sense that he doesn’t photograph for profit] whose work you’ll find in various corners of the net. If anything, his photography is a rejoinder to the cliche of getting close. His work possesses a dynamic power precisely because he’s chosen to stand back when necessary. For van Straten, the key is not getting near, or sufficiently far, but “being the right distance.”

*************

Erik van Straten was born in 1954 in Leiden, the Netherlands, and grew up in Amsterdam. In 1971 he was admitted to the photography department of the applied arts school in Amsterdam. While there he realized that professional photography didn’t interest him. Photographically, he went his own way while nurturing his own style.

He remains a dedicated film shooter and darkroom printer. He has never ‘transitioned’ to digital photography because a well-made gelatin silver print is simply more beautiful than any photo on a screen or from a digital printer. A traditionalist, he uses various film Leicas or a Nikon S2 with standard focal lengths of 50mm and 35mm. His preferred film is Tmax400, developed in Perceptol. He makes his prints with a Leitz Focomat IIc. The photos reproduced herein are scans of gelatin-silver prints he’s created in his darkroom. You can still see in them the beautiful gray tonalities and granular textures of the gelatin-silver process even when they’ve necessarily been scanned to be presented here.

*************

Refreshing in this age of disembodied digital processes, van Straten’s photographs remain material documents in addition to being visual observations. They possess the tactile elements of paper and emulsion. They are physical things one centers in frames and hangs on walls. A traditionalist, van Straten considers this materiality a necessary feature of a photograph.

I find van Straten’s photos to be beautiful in a literal sense, and that isn’t a criticism but a compliment. There’s a fullness about them, an intuitive sense of space that creates a coherent whole. They’re mannered without devolving into mannerism; they are representational and yet self-referential, realistic while being stylistic. His photos are simultaneously portraits of the individual and the archetype, a blend of the specific and the universal. If they are stamped with van Straten’s psychological imprint, they also have a universal aspect, a mythic quality – what Arther Lubow calls a “trinocular vision,” a confluence of personal, objective, and mythic. They are allegories playing out in the moment, liminal zones in which the everyday touches something eternal.

Buddy

Buddy, Sucking Up to My Brother-In-Law

If you’ve been reading me for any length of time, you’ll know I have a dog. Buddy. You’ll probably have picked up on the fact that I Love Buddy. A lot. Me and Buddy are a pair; where I go he goes.

I actually have two dogs, but I’m partial to Buddy (don’t worry – the other one gets my wife’s undivided attention). I’ve had him, now, for 8 years. My wife, visiting a local pound about another animal, was introduced to him by a kindly pound worker who had taken him to heart. Apparently, he’d been there since a pup and no one had the heart to euthanize him even though no one seemed to want him. Donna called me while driving home and told me about him. What the hell, I said, go get him and bring him home. So she did. It’s remarkable how such ‘off-the-cuff’ decisions can change your life. I love this boy in a way hard to explain.

Buddy is what I refer to as “a piece of work,” pure personality and joie de vivre. This past weekend he got banned from the dog park by my home for “improper behavior” i.e. he insists on humping the other dogs. His predilection for humping had heretofore been overlooked – tolerated – because in all other respects he’s a real sweetheart, just as pleasant and good-natured as they come. Unfortunately, he started humping puppies at the park. Apparently, humping puppies is crossing the line. He’s been banned.

*************

He doesn’t seem to be taking his banishment personally, which is to be expected. As I’m writing this, my wife has found him under the dining room table eating some gingerbread cookies last seen on a plate on the table. He’s remarkably nonchalant about the whole thing, feigning ignorance as to how the cookies might have made their way from the plate to the floor. Undoubtedly, in a few minutes, he’ll be happily nestled at my feet with a shoe in his mouth, his way of reminding me it’s time to go walk.

I’ve never had the first problem with him. As I said, he’s super sweet. He makes me smile. He’s just a sweet, goofy critter with a huge heart and unshakable loyalty to me. And he’s funny. I’m not sure how to explain his ‘sense of humor,’ as if a dog could have a sense of humor – but he does. He’s most definitely a funny guy. Look at the photo below, and tell me that guy doesn’t have a wicked sense of humor. Admittedly, I’m anthropomorphizing him. So what.

The Individual Thing

FOCA: The French Leica

The coupled rangefinder interchangeable lens Foca cameras, of French design and manufacture, spanned a 20-year period from 1945 until the middle of the 1960s