Film photographers never much cared about bokeh. The first time I think I even heard the word was when we were well into the digital era, probably on some internet forum, where the hive mind argue vehemently, and endlessly, about some non-sensical brain-splitting, optical hair-splitting issue, the functional analogue of mediaeval theological debates about just how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. When it comes to bokeh, what everyone agrees is this: whatever lens you buy, it’s got to have beautiful bokeh. Not angry bokeh, or harsh bokeh, or clinical bokeh. Beautiful bokeh.

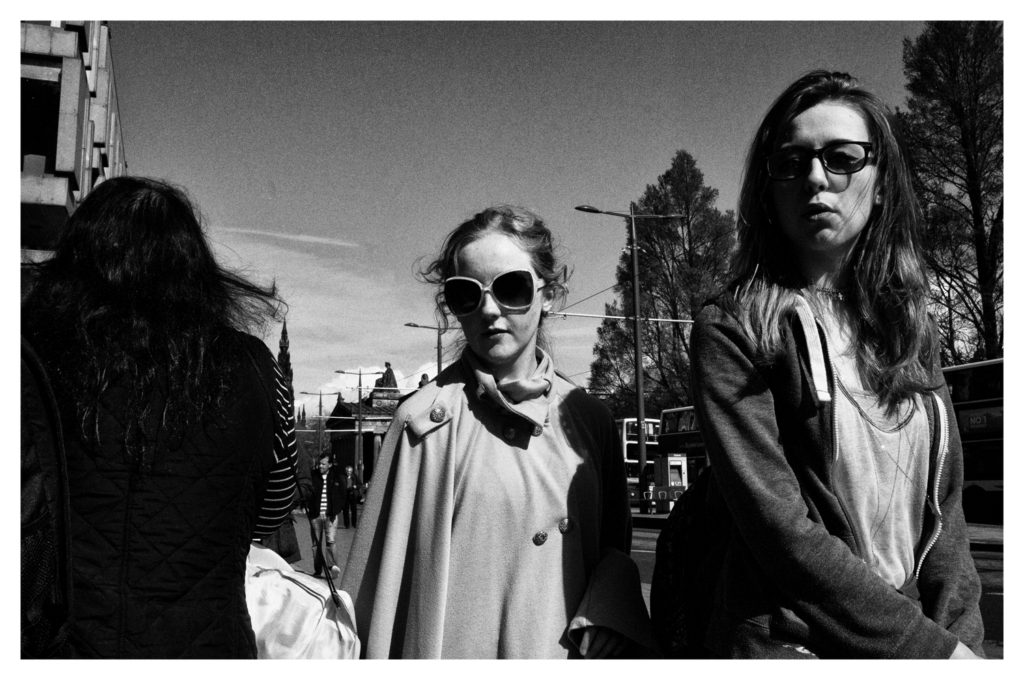

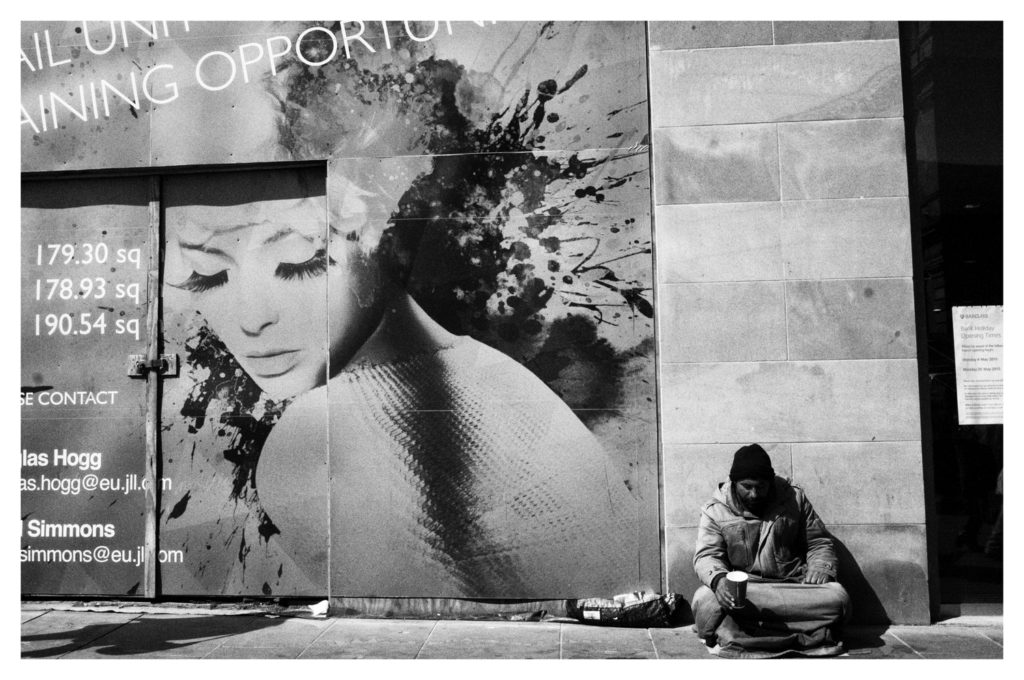

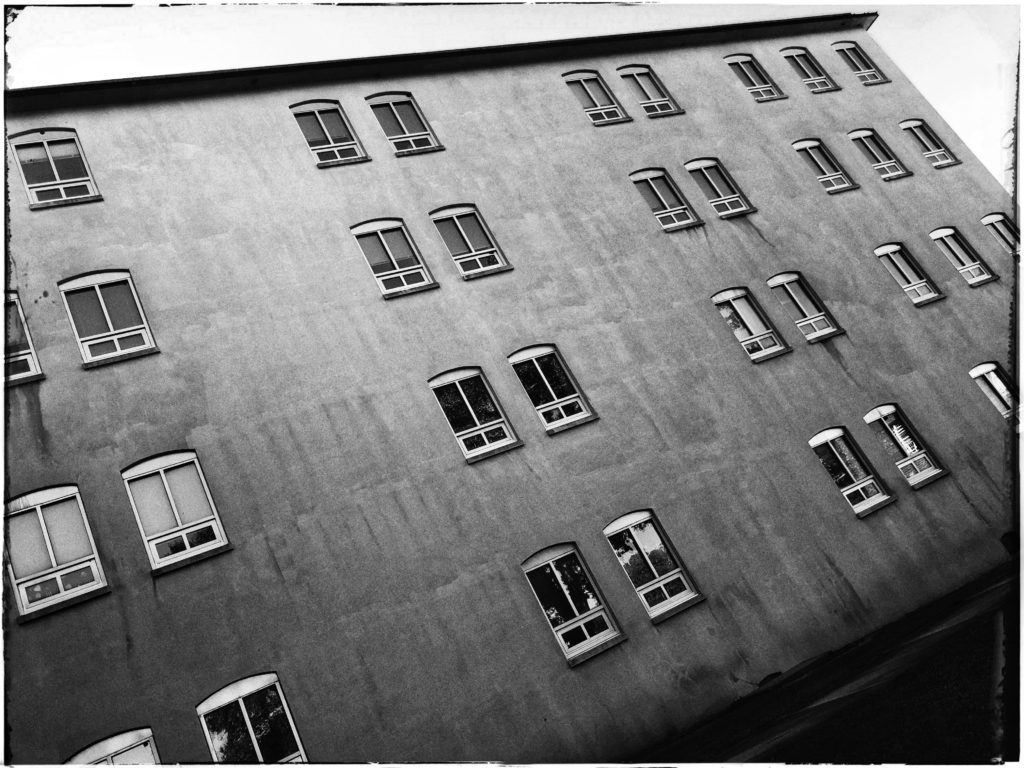

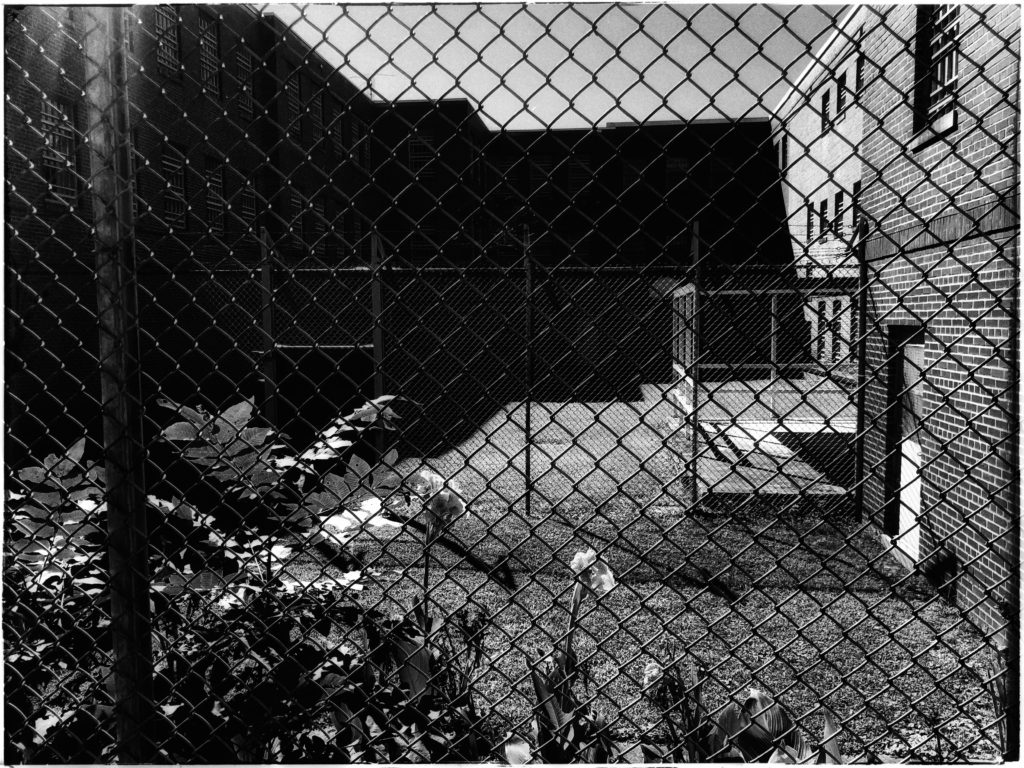

Bokeh is a digital phenomenon, a photographic meme that’s taken wing with the digital herd’s overriding obsession with optics. Or maybe, upon reflection, it isn’t so silly, but rather points up what I see as an inherent flaw in the nature of digital capture – the sort of transparent, ultra-lucidity of digital files, their noiseless purity that just looks….false. I can best describe it as a certain lack of presence, a sterility in continuous digital tones, obvious in how digital capture renders clear blue skies, skies that film renders, even when blank, with a certain heft and fullness. Digital renders skies thin and transparent, lifeless in their plastic perfection.

And I think this might be why we are now obsessed with bokeh: it’s this sterility in the very nature of digital capture that has brought to the fore our obsession with ways of masking it.

*************

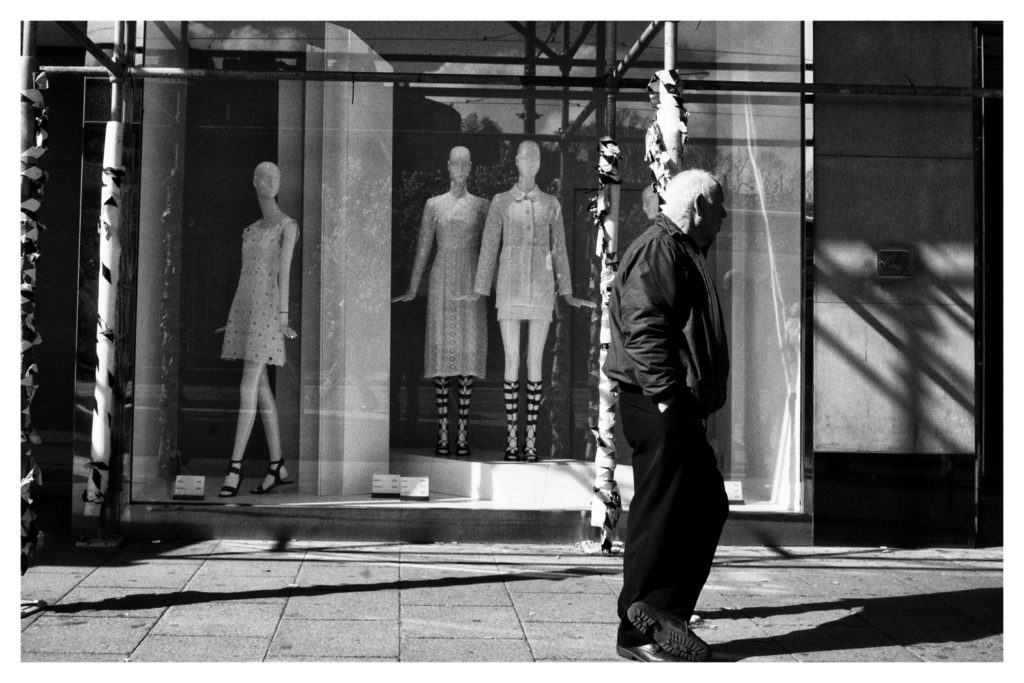

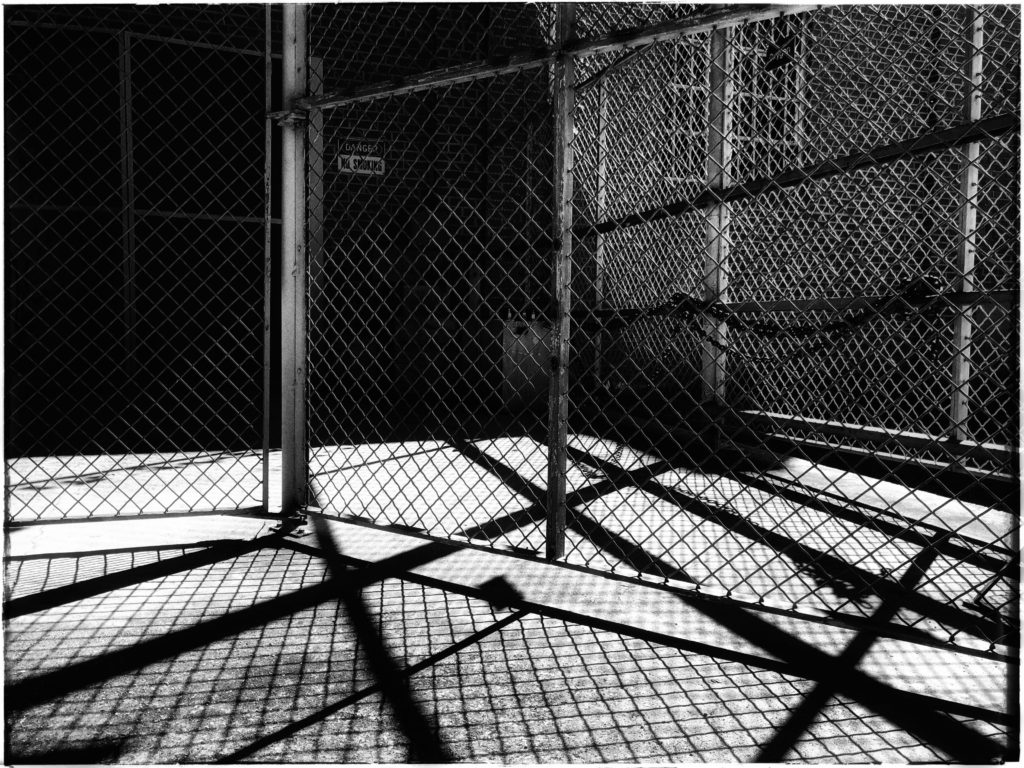

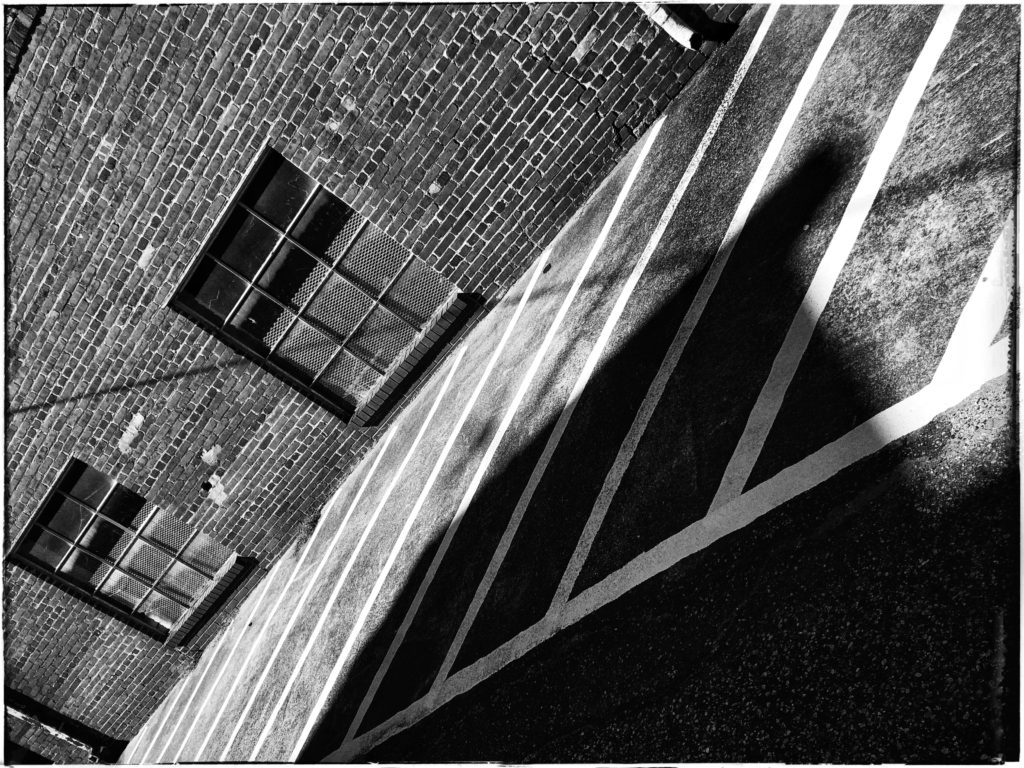

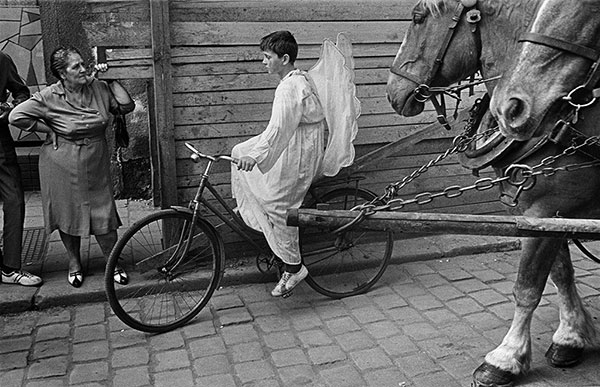

Narrow depth of field and subsequent emphasis on bokeh is a function of photography as a process. It’s not an organic offshoot of the human experience of seeing, but rather a photographic artifact, a result of the process of capture itself. It’s certainly not replicating a natural way of seeing. It’s what philosophers refer to as a “construct,” produced by the characteristics of photographic optics.

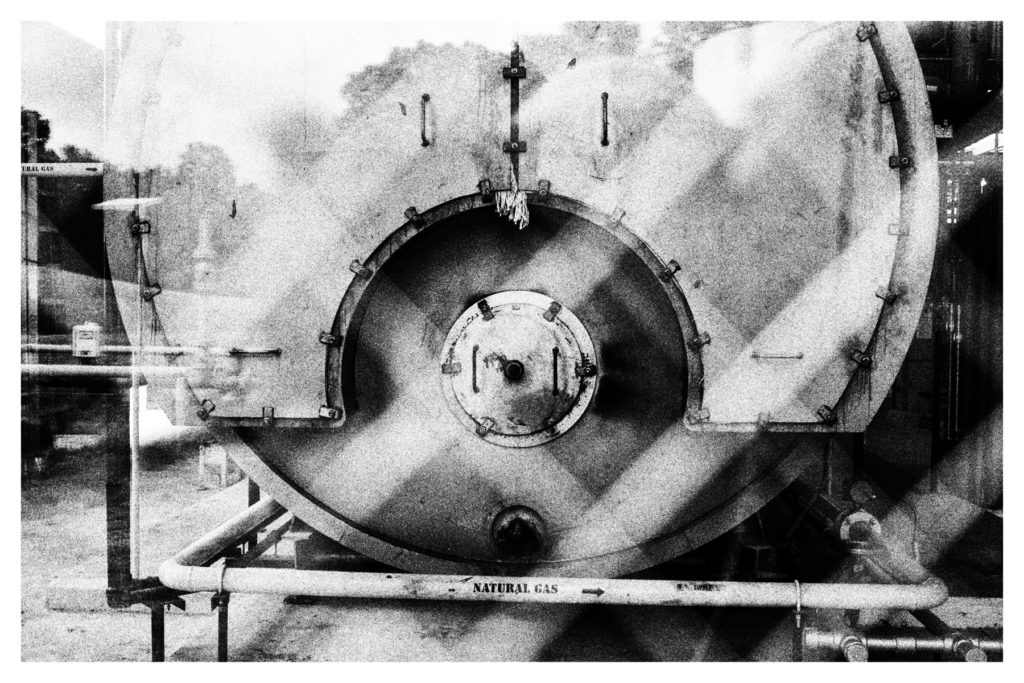

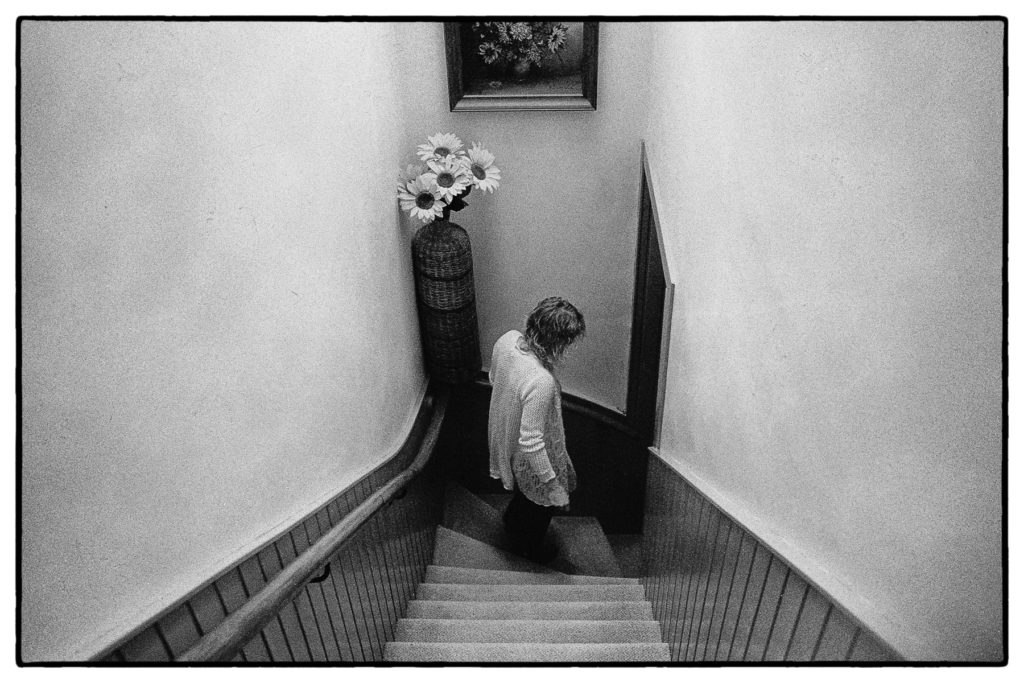

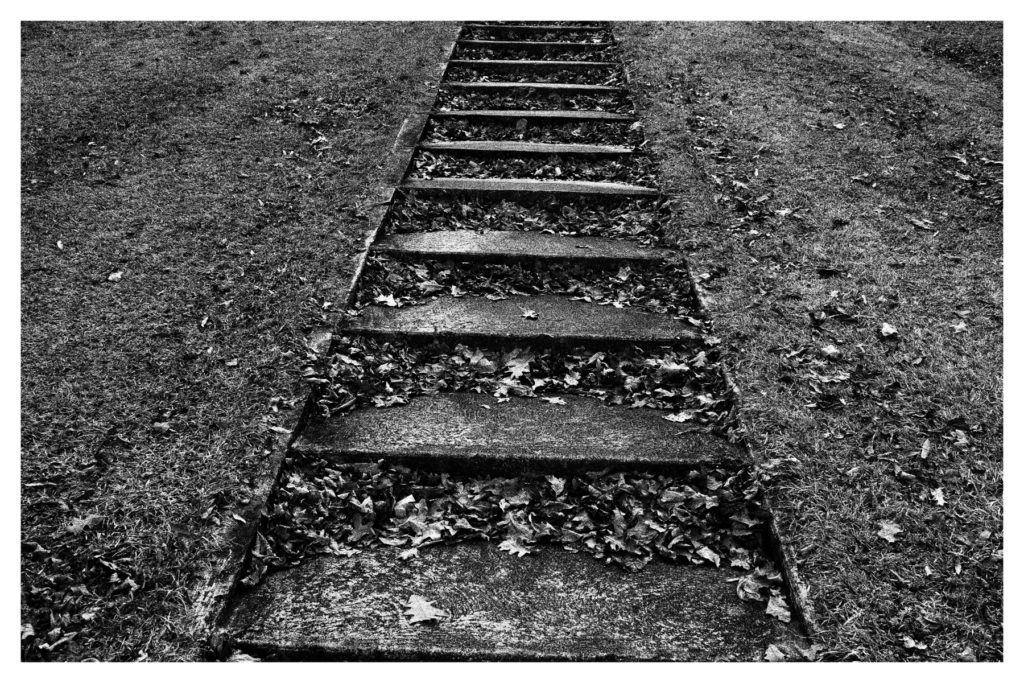

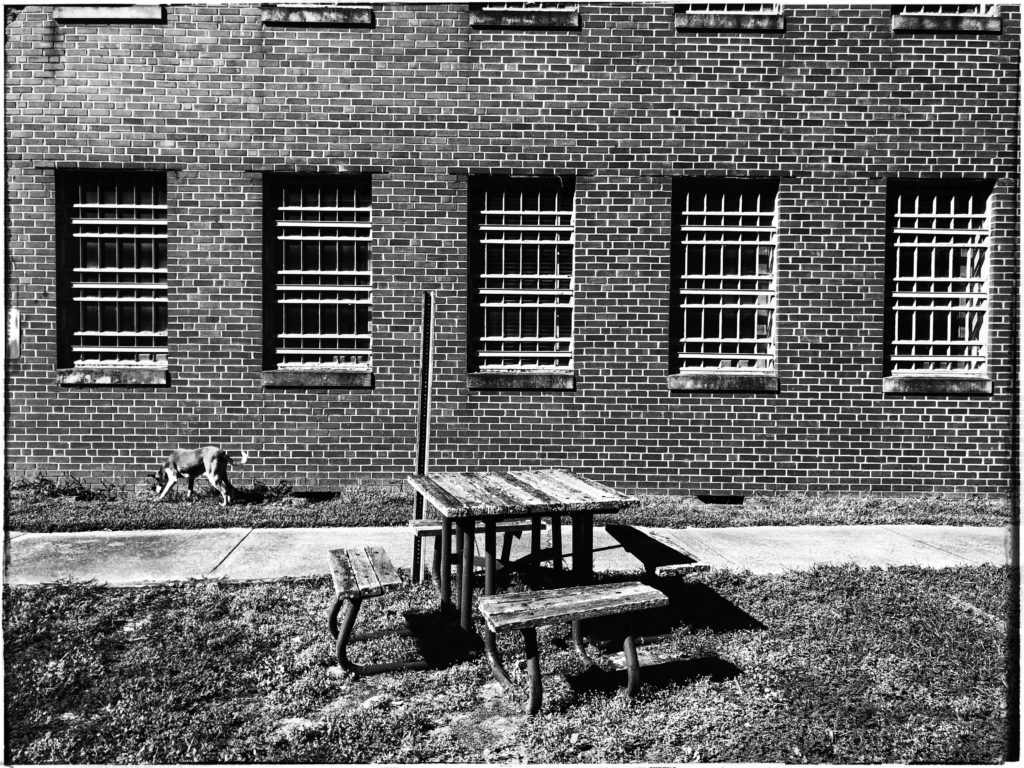

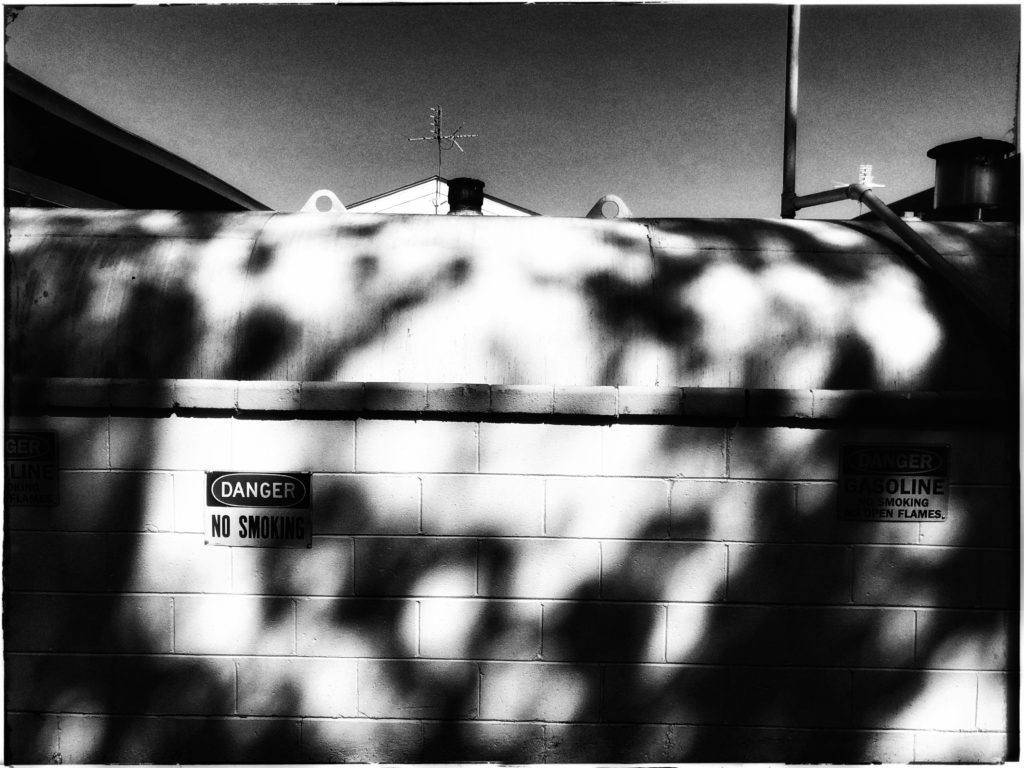

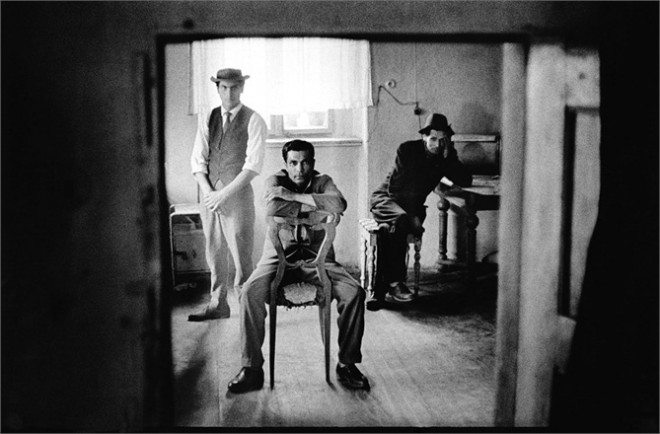

But so is grain. We don’t see grain. Grain is a traditional artifact of the film process. Grain gives that patina of distance, the step back from the real that helps us see the obvious – photographs aren’t transparent windows onto what is “out there”, they’re opaque at best, more a mirror turned back on the photographer than the view out if a window looking out.

I’m not advocating the position that an emphasis on bokeh (or grain) is somehow a violation of photography as a transcription of really. The underlying premise of that claim would be that there is one true way to recreate something photographically that corresponds to what is actually there, and the photographic effect we call bokeh is a perversion of that transcription. Of course, that notion is nonsense, based on the premise that photographs do, or even can, accurately transcribe reality.

The idea that photos accurately transcribe reality is a “common sense” opinion the average person holds about the basic integrity of the photograph as a reflection of what is “out there.” But it’s wrong. Some cultural philistine once sought out Picasso while he was resident in Paris. The guy wanted to tell Picasso he wasn’t a good painter because his portraits didn’t “look like” the people he was painting. Picasso asked him what he meant by “what people look like,” to which the philistine pulled a small B&W photo of his wife from his pocket, to which Picasso replied “so, your wife is very small, completely flat, and has no color?”

*************

So, bokeh is an artifice, added by the process itself, not inherent in how a scene represents itself to human vision. But so is grain. Bokeh is a relatively new phenomenon, created by fast optics that easily express – some would say overemphasize – it. Grain is produced by the silver halide process itself. Different processes, different effects.

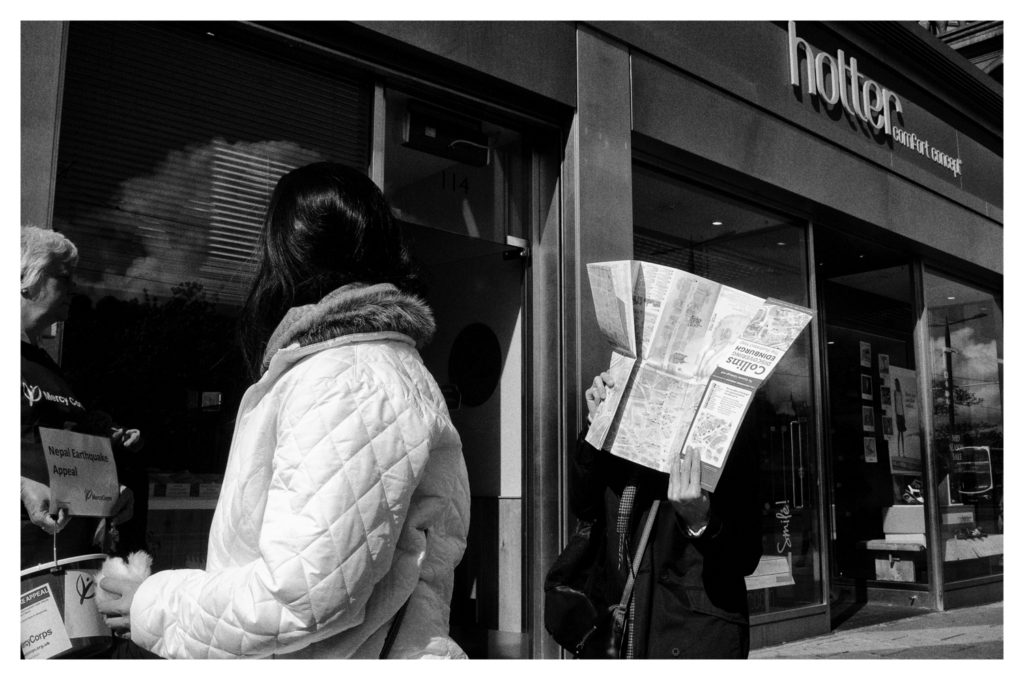

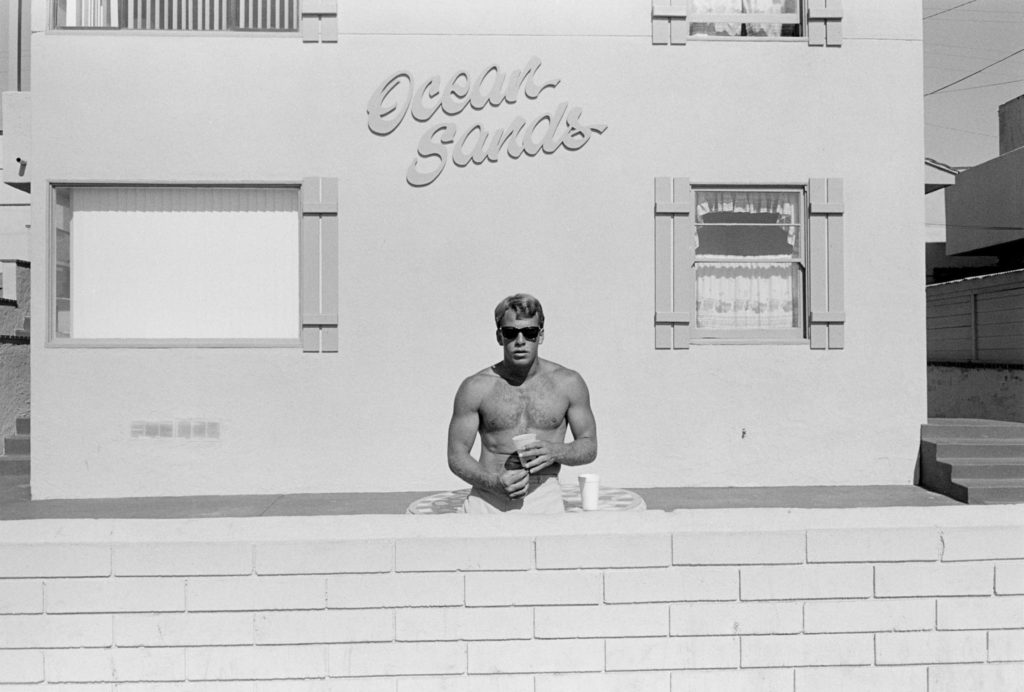

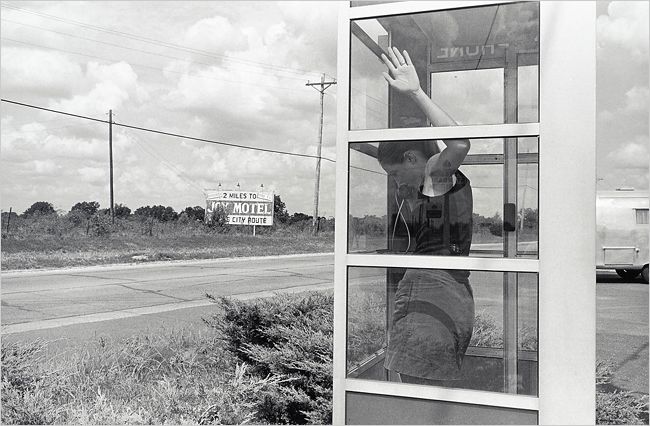

There was a time, in the pre-digital age, when photographers tried to minimize grain, seeing it as a flaw in the process, or, at least, accepted it as the cost of shooting ‘high speed’ films in available. light. If you look at Robert Frank’s American photos they’re grainy, not, I suspect, because he meant them to be that way but rather because it was a necessary effect of getting the shot at all. Of course, if you shot extremely slow films like Panatomic-X or Pan-F, you could largely avoid it up to a certain point, but the slow ISO of those films made the trade-off difficult. Hence, the ‘grain-less’ C41 films like Ilford’s XP2 Super. Ilford actually manufactured two “chromogenic” C-41 compatible black-and-white films, their own XP2 Super and Fuji’s Neopan 400CN. Kodak produced a similar film, BW400CN.

These films worked like color C-41 film; development caused dyes to form in the emulsion. Their structure, however, is different. Although they may have multiple layers, all are sensitive to all colors of light, and are designed to produce a black dye. The result is a black-and white image with no silver halide grain particles.

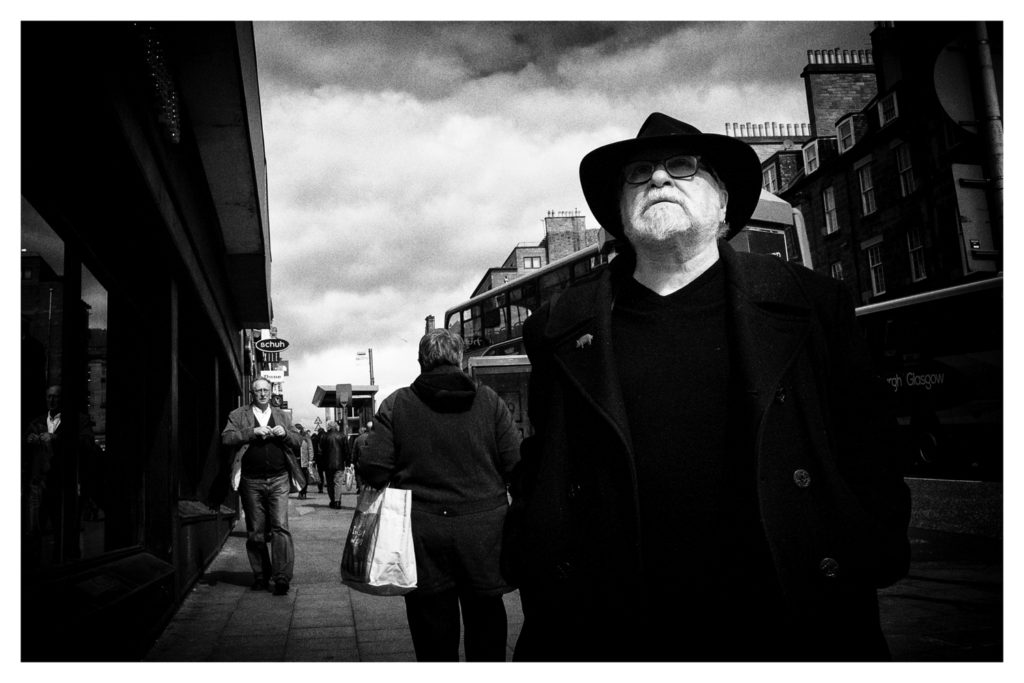

*************

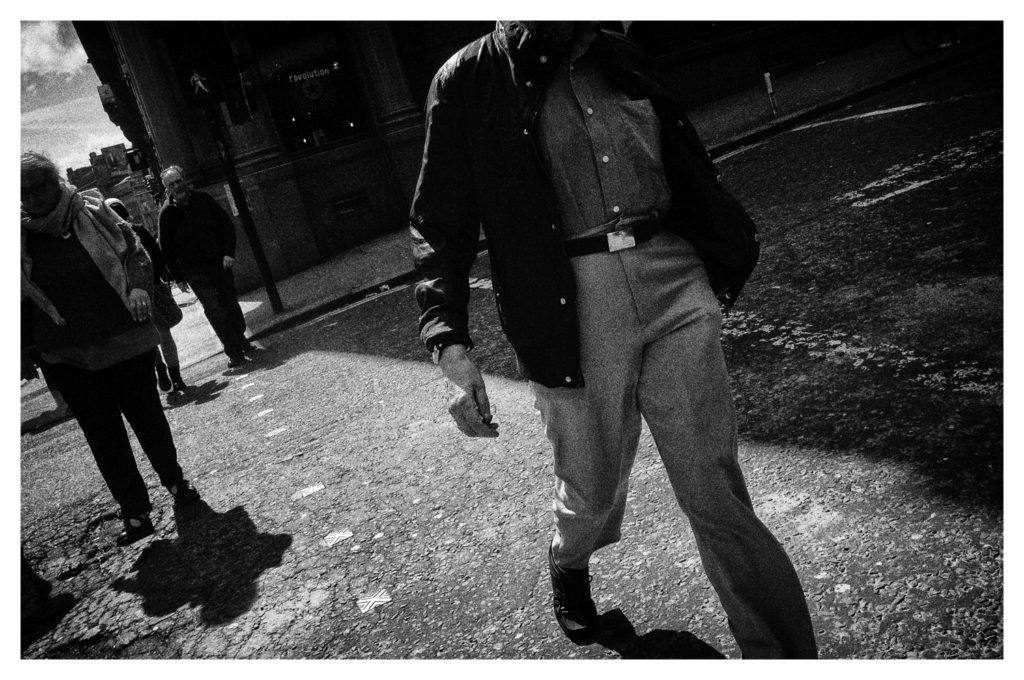

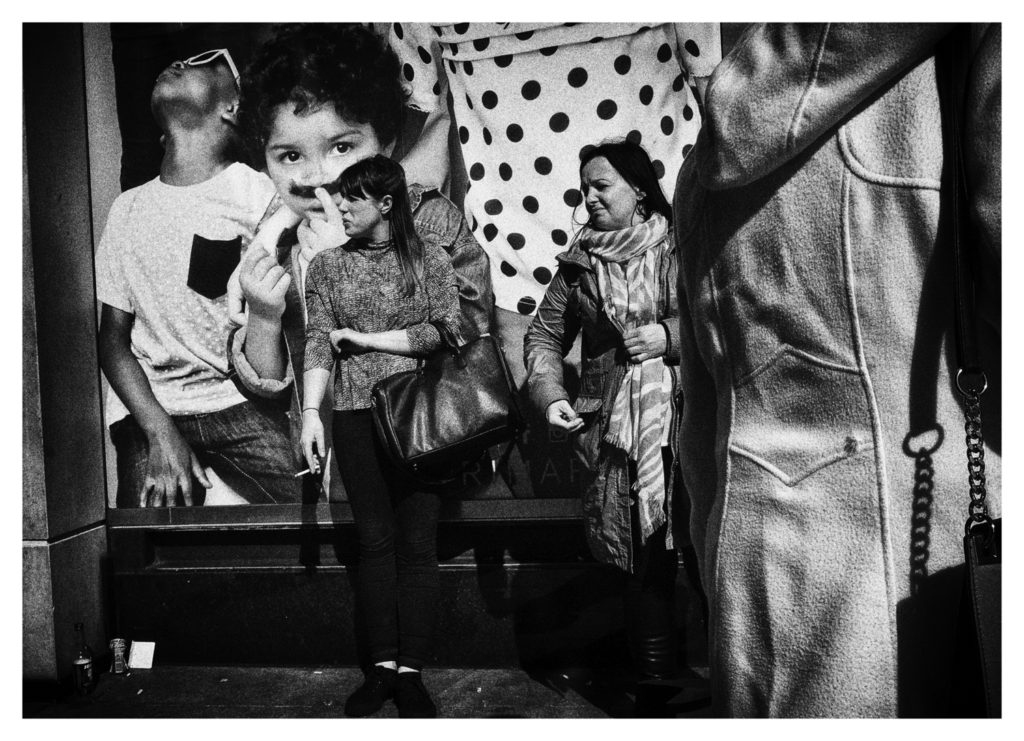

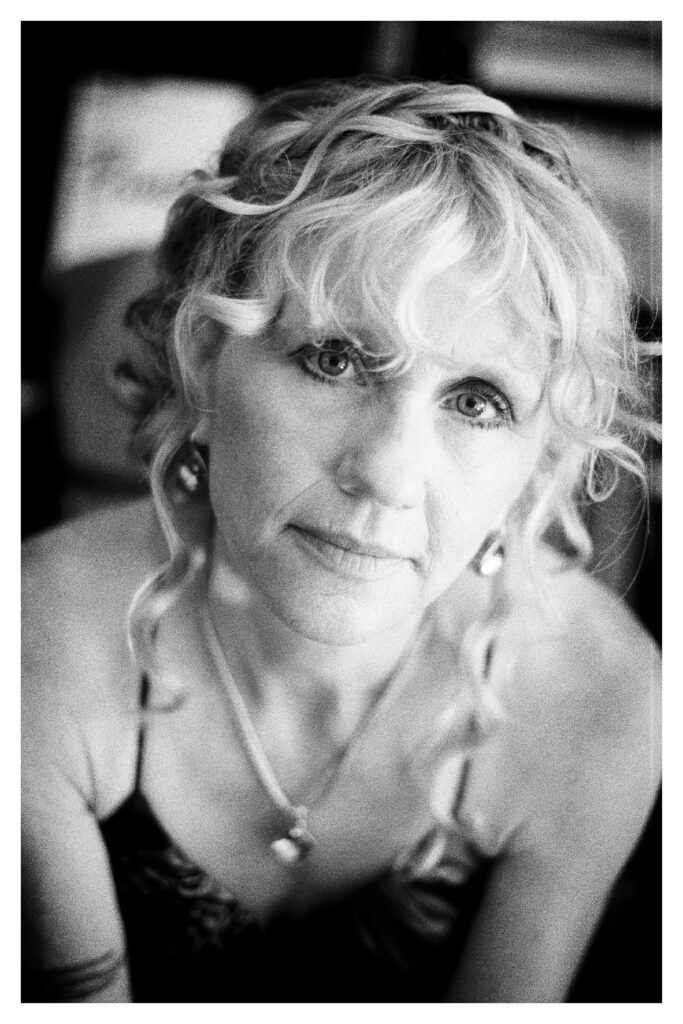

As a film photographer, I prefer some grain in my images. Certainly, now more so in the digital era when digital capture makes the ‘grainless’ look normal. I love the grainy look of Robert Frank in London/Wales, Valencia and The Americans. But I don’t think he was thinking of graininess when he photographed. He was just trying to get a workable negative. It’s ironic, then, that that heavy graininess has become so associated as an integral part of the work once digital capture came along. This emphasis on grain – which I’m prone to – is something I developed in the digital era. Grain gives me a way of giving a certain heft to the image; it’s why I typically shoot film above its box speed and develop in speed-enhancing developer like Diafine. I didn’t do that back in the day. I do it now because I think it’s what differentiates the film look from the digital look. It’s also why I run all my digital files through Silver Efex to, at a minimum, add grain structure to an otherwise ‘flat’ digital file. In this sense, grain has become as much a function of digital capture as has the emphasis on bokeh.