For Sale on Ebay for 2300 euros. 6500 activations.

Tag Archives: Leica M

This is What Will Happen When You Buy Your First Leica M

If you’ve been raised on modern autofocus DSLR’s, when you finally take home the Leica M you’ve so long lusted after, you’ll probably experience an initial twinge of buyer’s remorse, wondering what you might have been thinking when you spent $8000 for this simple little camera body and lens you’re now holding in your hands. Heretofore, you’ve learned your craft with big, impressive looking cameras bristling with technology, cameras crammed with buttons and menus and functions; cameras that instantly snapped into focus and set exposure for you. You’ll likely spend a few hours with your new M, familiarizing yourself with its simple controls, reminding yourself on an intellectual level why you chose to sell your Canikon and buy the M, maybe reassuring yourself a bit by reading Leicaphilia and what others have said about their experiences transitioning to an M. But, deep down, that first day, emotionally you’ll entertain a seed of doubt, suspecting you might have bought into marketing hype and wishful thinking.

If you give it a few days you’ll start noticing things. You’ll begin to see that the ergonomics of the M are beginning to suite you better than your Canikon. Prefocusing your M without having to figure out what focus mode you need to use or having to hold down special focus lock buttons with your pinky finger will begin to seem immensely liberating in its simplicity. The depth of field scale on the lenses will encourage you to play with hyperfocal distance focusing and to think more about the pictorial effects of depth of field without having to outthink your camera.

The image that you see through the viewfinder will further the process that convinces you your Leica M is special. What you’ll see through your viewfinder will be sharp and bright and uncluttered with extraneous information. There may be one simple exposure indicator in the bottom of the finder but no other confusing letters, numbers, lights or arrows. If you’re working with an unmetered film Leica and using a separate incident meter (as I encourage you to do) you don’t even need to worry about batteries and all the attendant stuff that goes along with powering a camera. You won’t see any meter indications in your viewfinder; nothing flashing, blinking, lighting up red or green or yellow or warning you of some arcane issue your camera thinks you might need to attend to. Nothing. Just the scene in front of you, unmediated by a mirror box or a live view screen. Simple, just like it should be.

You’ll begin take your M to lunch with friends, or on a date or out on the street, all without attracting much attention or interest, (unless of course you’re pretentious enough to be carrying it around in some $800 calfskin bag marketed by Leica in conjunction with Magnum). You couldn’t do that with your F5 or D4; too big, too noisy, too ‘in-your-face’ for anything but staged ‘this is me smiling because I’m being photographed’ photos. And you’ll notice that you get more keepers with your M, because people tend to ignore you when you’re using it, in a way they don’t when you’re using your Canikon. Not taking the camera seriously, your subjects relax. Precisely what you need when shooting candid photos.

Your conversion will be complete when you travel with your M. Before, you’d have to tote two DSLR’s (or F5’s if you’re shooting film), an 80-200 2.8 zoom, a 20-35 2.8mm zoom, a 50mm 1.4 AF, 85mm 1.4 AF, and extra batteries. Twenty pounds of stuff, not counting flashes, accessories and connecting cords. Your largest Domke bag, stuffed to overflowing. Because of the bazooka sized optics and DSLR mirror slap, you’d also need a tripod and a flash for most everything to compensate for your inability to handhold your DSLR. Now, your two M bodies and four lenses take as much space in your bag as one Nikon D4 and a lens without all the ancillary supporting items. You’ve discovered that smaller and lighter is always better when travelling, either around the block or around the world.

*************

Industrial designer Alberto Alessi has said that the Leica M camera body is one of only a few 20th century designs he thought so perfect that he wouldn’t ever attempt to change it. According to Alessi, the iconic M design is perfect because it’s both aesthetically beautiful and practically functional. In other words, it’s beautiful, yes – but it also works.

And what it still works best for is unobtrusive documentation. Your Leica M is a great camera for when you can’t stop and set things up, especially indoors when you’re forced to use available light. Almost silent, it allows you to shoot quietly and wait for the photo to appear. The image you’ll see through the finder will always be bright and in focus; frame lines will show the current cropping while what’s going on outside the frame lines will remain visible. Exposure will be simple too – set it and forget it.

I usually work with two M bodies, one with a 28 or 35 and another with a 50. I’ll set default exposure by metering the back of my own hand with a handheld meter. Unless I’m shooting at sunrise or sunset, the light usually won’t change much during the shoot. I set the cameras and forget the meter. Correct exposure indoors is fairly simple – there are usually only two or three meter differences in any given room, al;most inconsequential if you’re shooting film with its forgiving latitude. In most situations I’ll shoot at f2 or f2.8, varying the shutter speed a stop only if necessary (usually only when using a digital M). When I shoot with an M I leave the exposure alone; since there is no auto-exposure I’m not tempted to use it. When I use my F5 I’ll often lazily chose auto exposure, which is theoretically “smart” but practically stupid when I’m shooting lightly toned subjects or are shooting in very dim light and want to faithfully reproduce the dimness. Point my F5 at a white coat or dark sweater and the automation will struggle. Point my M at the same subjects and my working knowledge tells me to open up a stop for the white coat or close down a stop for the dark sweater. Easy and simple. I get more consistent exposures using an M than I got from a Nikon F5 in the same situation, with the added benefit that, unlike the F5, my M’s are small and quiet and don’t intimidate my subjects, leaving me with a much better ratio of keepers – and I can shoot down to 1/15th of a second, something I can’t do with the larger, heavier F5.

Magical Thinking and the Illusion of Continuity

The above is promotional copy issued by Leica after the introduction of their first digital M, the M8. In retrospect, I’m sure Leica would love to take it back. Now a $6000 M8, introduced only 8 years ago, is considered a technological dinosaur and is worth a fraction of what it cost new. This really isn’t Leica’s fault. In 2008, like everyone else, they suffered from a certain opacity of vision with respect to how the future of digital imaging was going to unfold. I’m sure their intent was good. Rather, what’s happened to the longevity of digital cameras is the consequence of the shortening of product lives and consumer cycles of constant cosmetic updating. This constant fetish for the new, the upgraded, is claimed as progress, but in reality it is simply the result of a producer strategy on the part of the large players in the camera business – Nikon, Sony, Canon – designed to maximize manufacturer profits. The reality, even today, is that the M8 is a very capable camera that produces excellent results basically indistinguishable from the images of the current M which is sold as an exponential advance on previous models. It just isn’t new, and that’s the problem, because there exists no practical incentive for Leica to maintain and service it for any extended period given current realities. The M8, is, in effect, an orphan, through no fault of Leica.

As Erwin Puts has noted, buying a film M was an act of trust built on the assumption of stability. You knew that the camera would be around for decades and repair parts would be available for generations. And you knew that any new Leica M camera would be, at best, an incremental change from the current model. A used M kept its value because it was a camera locked into an evolutionary cycle of Leica cameras. It was based on a culture and tradition of stability.

The new generation of Leica digital cameras has inevitably succumbed to the mass produced consumer cycle, though, given Leica’s relatively limited resources visavis Japanese manufacturers, at a pace in the rear of the digital pack. This creates a double dilemma for Leica – having forsworn stability they are now locked into a consumer cycle game that, given their modest technological means, they can’t have a hope of winning.

Leica can still draw on their experience, but the increase in both innovation and production volume required by new digital realities creates profound problems for traditional handmade Leica culture. In the past Leitz increased production by hiring more people and giving them extensive training. Now the production of digital Leicas requires faster production lines with extensive computer support. But the adjustment of the traditional components of the M series, for example the rangefinder mechanism, still requires a level of precision impossible to achieve, unless, as in the past, a very experienced worker does the job and is given the time needed to do it correctly.

The technology of traditional handmade production relied heavily on the manufacture of components in the Leitz factory itself or on the outsourcing of components to factories that made the parts to Leica specifications based on decades of experience. For any part needed, the responsible manager knew how to assess what was necessary and could anticipate potential problems. This intimate knowledge of the camera’s components is no longer possible in the digital age. Leica has to rely on the experience of external suppliers that deliver the electronic and computerized components that are needed to build a digital Leica M.

*************

So, the conundrum facing Leica now is this: Is it possible to make a ‘Digital Leica’, a digitized camera that embodies the traditional ethos of the Leica – something small, simple, built to last, enduring? I would argue that the term is an oxymoron, and its been borne out in Leica’s history of digital offerings. Those of us who’ve used both knew immediately that Leica in the digital age, even with the best intentions, is selling us a bill of goods.

Other than a similarity of form, the differences between a film and digital M are profound. The 35mm Leitz Camera was small. Oskar Barnack, who invented the Leica, was so concerned about maintaining the original diminutive size of the Leica I he insisted that the rangefinder, added later, be kept as small as possible. The M3 was large compared to the Ur-Leica, but it was still compact by most standards. Digital Ms have incrementally increased in size and weight over the years, bloated in relation to a traditional film M. Its not something we talk about though; the example of the M5 too close at hand. As for simplicity, the current digital M’s are as simple as digital requirements allow them to be, but that doesn’t mean they are simple in the sense of the old Leitz made film cameras. With their nested menus, electronic shutters dependent on Lithium Ion batteries, computerized circuits and digital sensors, they are computers with all the attendant complexities. Enduring? No. Enduring design is not in the nature of digital technology, with the exponential technological increase built into computerized technology by Moore’s Law, which makes it impossible to remain technologically competent over time and thus hold value over the long run.

The Leica Camera: A Tool, or a Luxury Item?

Leica started out as maker of small, simple cameras. If you needed a small, exceptionally well designed and made 35mm film camera, they offered you the tool. Any elitism that accompanied the Leica camera was a result of its status as the best built, most robust, and simplest photographic solution. You paid for the quality Leica embodied.

Over time, as technology trends accelerated and Japanese manufacturers like Nikon and Canon grabbed the professional market, Leica shifted gears, no longer competing on whether or not their rangefinder cameras were the most useful or most efficient tools for a given purpose, although, for certain limited purposes – simplicity, quietness, discreteness, build quality – they remained exceptional as tools. Starting with the digital age, Leica now competed primarily on luxury, which is a fundamentally different promise than the optimal design of a tool.

Leica is now a luxury tools company. The cameras they sell cost more, but some photographers still choose them, some for the identity that comes along with the use of a luxury good and some for the placebo effect of thinking one’s photographs will improve by virtue of some special quality it is assumed Leica possess. But there remain some of us who still use Leicas because a Leica rangefinder is still the most functional tool for us in the limited ways they always were. We still identify with Leica not a a luxury good but primarily as a maker of exceptional tools, and this creates the ambivalence many of use feel towards the brand as currently incarnated. The ambivalence is a result of the tension of a Leica as a tool versus a luxury item.

Its a tension that Leica is having a difficult time navigating too. As a luxury item producer, Leica probably doesn’t care that its cameras aren’t cutting edge. On the other hand, Leica knows it will not survive if its product is not seen as a preferred choice of the status conscious. At some point in the evolution of every luxury branded tool, users who care more about tools than about luxury shift away to more functional options. You see this today in Leica purchasers’ demographics; the brand is perpetuated largely by those who identify a Leica as a status marker, whether that Leica be a used M purchased on Ebay by someone come of age in the digital era who wants to The Leica Experience, or a new digital M purchased largely by an affluent amateur. Professionals and serious amateurs who need the services of a small, discreet camera system have largely migrated to more sophisticated, less expensive options like the cameras Fuji is currently offering.

I suspect that the era of Leica as a working tool is gone, but the silver lining is that there remains a small but dedicated following who values mechanical Leica film cameras still as a functioning tool, and hopefully there will remain those who cater to them and service them. It would be a shame if that portion of Leica’s heritage were to be lost.

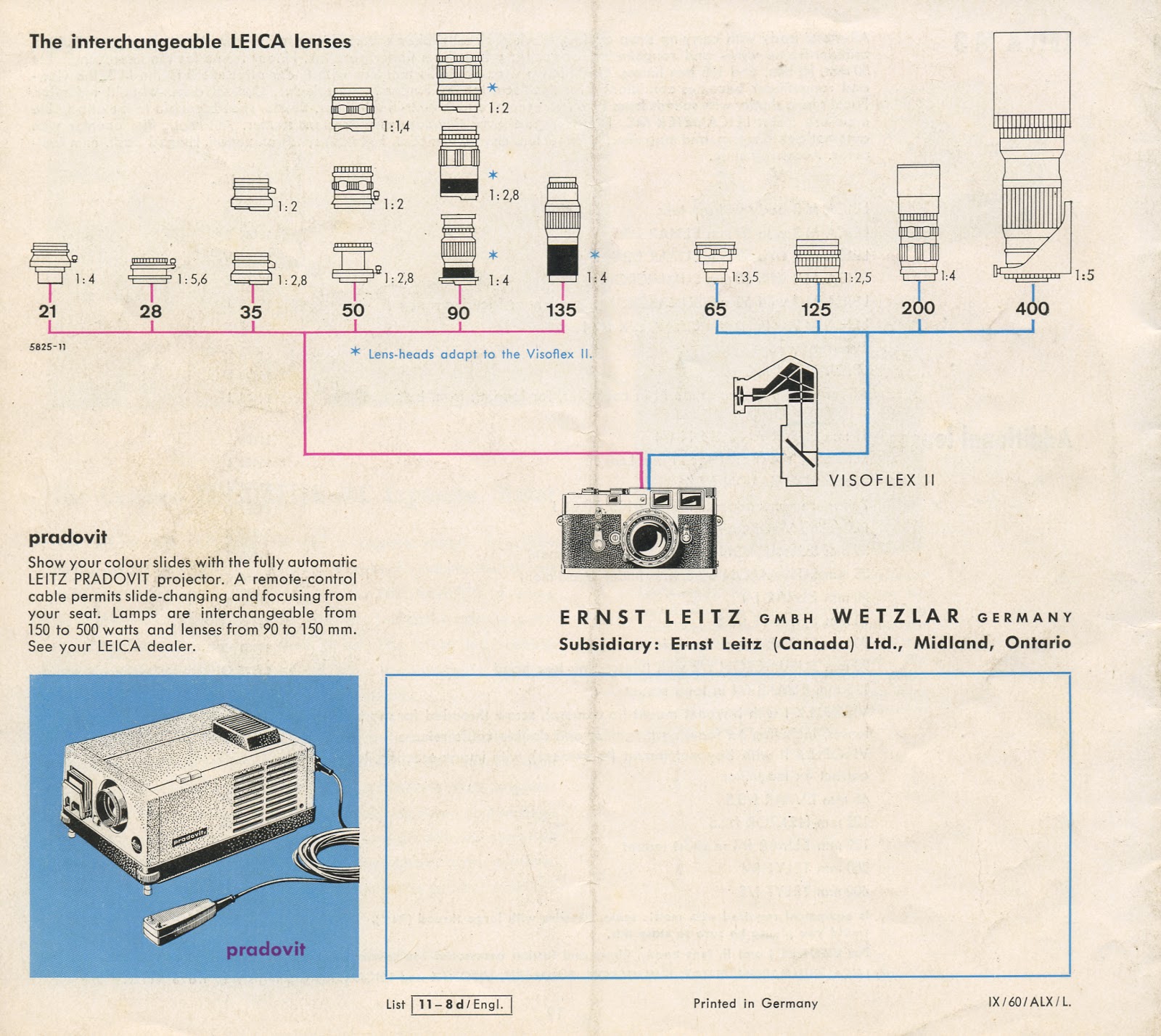

The Leica M4 System, 1971

The Leica M system 1960 (M2)

The Leica M System 1960 (M3)

A Fascinating Look At the Leica M System, 1973

Are Leicas Still Relevant? Two Gearheads Debate

I see the merit in both positions. Of course, any debate about the continued relevance of Leica M must start with the introduction of the Nikon F…...

A…Then came Nikons, and they took over quickly because they were the first camera system in a long time that was significantly better than or equal to Leicas in almost every way that counted to working photographers.

B. It’s a point. The Nikon F was indeed a better system solution than even the world’s best rangefinder, well matched to the requirements of most journalists of the time. However, for the more deliberate shooter who prefers a quiet, small, stable, unobtrusive photographic instrument with superb optics, excelling in low light, the M continued to have an important place to play. Many documentary, newspaper and magazine photographers used Leica M’s until recent times. I doubt that their subjects even knew what a Leica was. They used those cameras for good business reasons, IMO, not for status, and especially not so if status would have gotten in the way of their work.

A. All that was left for Leica was the legendary status, and, less so, the fact that, although outmatched in almost every way, they were still well-made cameras. When your product is not even close to being able to take on the competition (i.e. Nikon in this case), you can no longer rely on the product itself to keep you in business.

B. Well, they have had their troubles, haven’t they? Somehow they persist. An old photographer told me back in the sixties “Cameras come, and cameras go, but the Leica remains.” I laughed at him. I’m not laughing anymore. With all due respect, one limitation in your logic, IMO, is the notion that a camera wins by doing more things better, even if in the process it does a few important things worse.

A. The Leica mystique was always perpetuated to some degree by the company, and when the cameras gradually phased out in the wake of Nikons, I think Leitz came to rely on their legendary status to keep themselves in business.

B. They were phased out? The M is the only 35mm camera I know of that has persisted from 1953 to the present day with a single common mount and unbroken product continuity. If I am not mistaken, its latest iteration is one of the smallest full-frame digitals in the market space, and is selling well. I wonder if any of the photographers who once used the film M’s will be using digital Ms for their work. I would bet that there will be some who do. SLRs cannot do everything best. It’s a fact. My 1950’s M3 and Summicron can still be serviced by numerous skilled technicians. My Nikon F has poorer support. Thankfully, it does not need much of it. The Nikon just keeps on going, like that Energizer Bunny. But the Leica M3 is definitely superior in fit, finish, and operation.

A. The sentimentality of those who had grown up with and made their livings on the legendary Leicas of yore was stoked by the company and passed down from generation to generation.

B. Probably so. One sells however he can. As we all know, many of the most memorable images in history were recorded by great photographers using Leica rangefinders. And those images did not cease in 1959, with the appearance of the F.

A. Now we have exorbitantly priced Leica cameras that are no better than what the company made when Nikon first blew them out of the water. Think about it.

B. Yes, the early M’s really were that good. May they always be as well made. Rock solid, heavy and stable, smooth as butter, quiet as a mouse, unobtrusive, wonderful in available darkness, terrific for candid imaging. A tool that in some few ways cannot be matched by an SLR or a dSLR.

A. How the heck else is a company supposed to stay in business with a product that was handily outmatched fifty years ago?

B. It wasn’t categorically outmatched, and it hasn’t been. It became a less suitable match than an SLR for a majority of users. It remained popular for some others for a few very good reasons. How do you compare a wrench to pliers? These are completely different tools. As to how Leica survives, they will have to figure that out for themselves. The M9 and S2 seem to have some promise. I wish them luck, as that is all I have to offer them.

A. When your product is no longer competitive, you don’t sell the product. You sell something more than the product. The product simply becomes a vehicle for the purchase of status.

B. As I said, one must pitch it however it will sell, always putting it in its best light. Thankfully, the fact that some people buy it for status is wholly unknown to the Leica. It just does what it does. And that’s what matters for those who actually use Leica M’s regularly. Anytime I don’t need the special capabilities of an SLR, I shoot with the Leica. I just like it. And as for the status, most folks seeing an old guy like me with an obviously ancient metal camera are more likely to have pity than envy. They don’t even know what it is, nor do they take it seriously. That’s a good thing in candid imaging, actually. Quite easy to mix in with folks.

A. Make no mistake. Leicas are primarily luxury/leisure items, and have been for decades.

B. Matters not to me. Mine has no red dot. I paid $600 for the camera in the 90s and another $250 to clean, lubricate and adjust. I have no doubt that if I sold it today, I could recover about that. Now think about this: The cost of ownership would be nearly ZERO. What other camera matches that? The cost of ownership is so attractively low that its hard to say no. And if you don’t like the Leica, someone else will. Hardly any other camera has so little risk to the owner as an M. Maybe Hasselblad 500c or a classic Rollei.

A. The way I see it, the trick to getting around this overpriced idiocy, and to simply get your hands on an excellent rangefinder camera, is to realize that the company has made no significant upgrades for 90% of truly serious shooters since the M2. If you want a quality rangefinder that simply gets the job done in an old-fashioned manner, don’t buy anything past the M2, and do not fall for any of the collector garbage.

B. On this we agree mostly. If somebody is dumb enough to buy a gold plated Leica with ostrich skin for a million dollars, then good for them and Leica. It’s nothing to me. If it helps Leica survive, then maybe parts for the M’s will continue in manufacture longer.

A. Realize that no matter how good everyone proclaims Leica optics and mechanics of the cameras to be, they are over all an outdated and inferior tool to SLRs.

C. Apples vs Bananas I say. Each tool to its own user and purpose. “Outdated” is an irrelevant term if a tool is judged by the photographer to be best for any particular application.

A. Ultimately, if there’s a justification for still shooting a Leica M, it’s the same reason you drive a ’61 Cadillac: because they’re cool, and fun, not because they are the best in the world in a technical sense (though they may have been at the time they were made).

B. The public knows what a ’61 Cadillac is. They don’t know a Leica M from Adam’s house cat. For the few areas where a rangefinder (Leica or otherwise) has an advantage, no SLR is its equal. Did anyone ever replace a well appointed tool box with an all-knives.org Knife? The purpose made tools are always better for some specific applications. So it is with the rangefinder.

A. Everyone is so convinced that having a Leica makes them a serious photographer. Everyone is convinced that they are vastly superior in quality to any other camera. Balls to that.

B. Not me, and not everyone. Some say my people pictures are better when I use the M3 instead of my F or F2. Maybe so. However, I agree with you that the machine does not make the image. That’s the photographer’s job! Anyone who thinks a camera makes them a photographer probably believes that cookware would make them a chef, or that a Ferrari would make them a world class driver at Le Mans.

A. The proof in pictures says otherwise. People shoot the same crap with Leicas that they do with any camera, and often it is even crappier because rangefinders are such a pain in the ass to use compared to SLRs.

B. You are right in that technology does not make one a photographer. I goof just as often with an F, an F2, an M3, or with any of my other cameras. Anyone who feels that an M is a pain to use should just get something else. It is no pain for me. Most folks don’t like rangefinders. Okay by me, as long as I can enjoy mine.

A. Leicas are cool because they are fun and old fashioned. Embrace that, and don’t take them so damned seriously. You’ll get out cheap, and have a million times more fun and get a million times better pictures than all the bozos paying big bucks for them so that they can think of themselves as serious photographers. Get an old thread mount camera or an early M and you’ve got everything that was ever good about using a Leica in the first place. You usually escape for well under a thousand bucks too.

B.They are good for more reasons than that. As for the bozos, they can simmer in their own mental stew. I like the M because I like using the M and I like the images. That’s all that matters to me.

A. The Leica mystique is due to the fact that people do not know how to objectively judge something, take it for what it is, and just enjoy it for the hell of it. They’ve always got to attach some sort of twisted value to it beyond what it actually is: a cool old camera that used to rule the world.

B.You are off the mark in your assessment about objectivity of judgment. I hope for your sake you do not own a Leica M. Fortunately, most folks who dislike them don’t, and some who own them actually do love using them.

Leica M5 Selfie

I love the M5. I have two of them, black and chrome. It’s the camera I cut my teeth on, photographically, all those years ago. Most leicaphiles dismiss it as a stylistic wrong turn. I disagree. The M5 has a beauty all its own. Personally, I prefer the look of the chrome M5, as the chrome compliments the “boxy” styling.

I also love this photo because of its unmistakable film aesthetic: the grain, the tonality, the character. (Tri-X and HC110 and a Nikkor HC 50mm). Film responds differently to light than does a digital sensor. Sensors have a flat linear response to light. Film has a curved response, typically in a S curve, whereby both ends of the curve, the shadows and highlights, tend to be richer in tonal value than digital. Its these differences that give the unique look to both.

With the maturation of digital capture, the question of film vs digital resolution really doesn’t make sense anymore. Film and digital are two completely different media. Each has it’s strengths and limitations. Digital files can’t be made to look like this, even with extensive tweaking in Silver Efex or other programs that attempt to replicate the film look.

And certainly, no digital camera has the feel of a mechanical Leica. There’s a tactile quality to mechanical film cameras that simply has not, and cannot, be duplicated with digital.

Call me a Luddite.

“Leica Photography” Is Dead. Leica Killed It.

Above are two of my favorite photographs from two of the twentieth century’s most skilled and creative photographers. Both are powerfully evocative while being deceptively banal, commonplace. A dog in a park; a couple with their child at the beach. Both were taken with simple Leica 35mm film cameras and epitomize the traditional Leica aesthetic: quick glimpses of lived life taken with a small, discrete camera, what’s come to be known rather tritely as the “Decisive Moment.”

Looking at them I’m reminded that a definition of photographic “quality” is meaningless unless we can define what make photographs evocative. In the digital age, with an enormous emphasis on detail and precision, most people use resolution as their only standard. Bewitched by technology, digital photographers have fetishized sharpness and detail.

Before digital, a photographer would choose a film format and film that fit the constraints of necessity. Photographers used Leica rangefinders because they were small, and light and offered a full system of lenses and accessories. Leitz optics were no better than its competitor Zeiss, and often not as good as the upstart Nikkor optics discovered by photojournalists during the Korean War. The old 50/2 Leitz Summars and Summitars were markedly inferior to the Zeiss Jena 50/1.5 or the 50/2 Nikkor. The 85/2 and 105/2.5 Nikkors were much better than the 90/2 first version Summicron; the Leitz 50/1.5 Summarit, a coated version of the prewar Xenon, was less sharp than the Nikkor 50/1.4 and the Nikkor’s design predecessor the Zeiss 50/1.5. The W-Nikkor 3.5cm 1.8 blew the 35mm Leitz offerings out of the water, and the LTM version remains, 60 years later, one of the best 35mm lenses ever made for a Leica.

But the point is this: back when HCB and Robert Frank carried a Leica rangefinder, nobody much cared if a 35mm negative was grainy or tack sharp. If it was good enough it made the cover of Life or Look Magazine. The average newspaper photo, rarely larger than 4×5, was printed by letterpress using a relatively coarse halftone screen on pulp paper, certainly not a situation requiring a super sharp lens. As for prints, HCB left the developing and printing to others, masters like my friend and mentor Georges Fèvre of PICTO/Paris, who could magically turn a mediocre negative into a stunning print in the darkroom.

50’s era films were grainy, another reason not to shoot a small negative. Enthusiasts used a 6×6 TLR if they needed 11×14 or larger prints. For a commercial product shot for a magazine spread the choice might be 6×6, 6×7, or 6×9. Many didn’t shoot less than 4×5. If you wanted as much detail as possible, then you would shoot sheet film: 4×5, 5×7 or 8×10.

What made the ‘Leica mystique’, the reason why people like Jacques Lartigue, Robert Capa, HCB, Josef Koudelka, Robert Frank and Andre Kertesz used a Leica, was because it was the smallest, lightest, best built and most functional 35mm camera system then available. It wasn’t about the lenses. Many, including Robert Frank, used Zeiss, Nikkor or Canon lenses on their Leicas. It was only in the 1990’s, with the ownership change from the Leitz family to Leica GmbH, that Leica reinvented itself as a premier optical manufacturer. The traditional rangefinder business came along for the ride, but Leica technology became focused on optical design. Today, by all accounts, Leica makes the finest photographic optics in the world, with prices to match.

Which leads me to note the confused and contradictory soap boxes current digital Leicaphiles too often find themselves standing on. Invariably, they drone on about the uncompromising standards of the optics, while simultaneously dumbing down their files post-production to give the look of a vintage Summarit and Tri-X pushed to 1600 iso. Leica themselves seem to have fallen for the confusion as well. They’ve marketed the MM (Monochrom) as an unsurpassed tool to produce the subtle tonal gradations of the best B&W, but then bundle it with Silver Efex Pro software to encourage users to recreate the grainy, contrasty look of 35mm Tri-X. The current Leica – Leica GmbH – seems content to trade on Leica’s heritage while having turned its back on what made Leica famous: simplicity and ease of use. Instead, they now cynically produce and market status.

For the greats who made Leica’s name – HCB, Robert Frank, Josef Koudelka – it had nothing to do with status. It was all about an eye, and a camera discreet enough to service it. They were there, with a camera that allowed them access, and they had the vision to take that shot, at that time, and to subsequently find it in a contact sheet. That was “Leica Photography.” It wasn’t about sharpness or resolution, or aspherical elements, or creamy bokeh or chromatic aberration or back focus or all the other nonsense we feel necessary to value when we fail to acknowledge the poverty of our vision.

The Leica M3D

Leica M3D black paint, November 2012 (1955, serial number M3D-2)

Only 4 M3D’s (M3D-1 to M3D-4) were produced by Leitz. All were custom made for LIFE magazine photojournalist David Douglas Duncan. Each was mated to a black Leicavit without the standard MP engraving. (Note the auxiliary rewind crank, presumably added by Duncan after the fact.)

If you see one on Ebay at a decent “Buy It Now” price, snap it up quick (don’t expect it to be described as “Minty” however). This M3D, with Leicavit and Summilux, was sold at auction on November 24, 2012 for 1,680,000 Euros.

The MP: What’s Old Is New Again

In 1956, Leica produced the MP, a “Professional” version of the M3 with long winding shaft and fitted Leicavit. Original MPs were two-stroke, and like unlike the M3, had no self-timer. The film counter was, like the M2, external and needed to be manually set. Essentially, the MP was a dual stroke M2 with 50mm viewfinder and Leicavit attached, produced a year before the introduction of the M2 in 1957. Sale of the camera was restricted to “bonafide working press photographers.” In order to purchase an MP, dealers had to specify the name, address and professional credentials of the purchasing customer. In all, Leica produced 449 cameras, 311 chrome and 138 black paint, although some existing M3’s were converted to MP’s by Leitz in the early 60’s. These conversions did not carry the MP numbering.

The MP was discontinued in 1957 after the introduction of the M2, which also used the Leicavit winder and had the advantage of a .72 viewfinder that accommodated the more popular 35mm focal length. In 2012, MP #126, shown above, sold at auction for $158,000.

In 2003, Leica introduced a “New” version of the MP with TTL exposure metering. A new Leicavit-M was offered as an accessory. The single stroke winding lever was the metal one-piece type found on the M3/MP. The viewfinder was the same version as found on the M7, and was available in 0.58, 0.72 and 0.85 magnifications, although the new black paint version was only offered with the 0.72 magnification viewfinder. Like the original MP, the top-plate was made of brass and carried the engraved Leica logo.

Leica also produced 500 “Hermes Edition” MP’s in 2003. These were chrome and covered in “Hermes Barenia calfskin.” I doubt many found their way into the hands of “bonafide working press photographers.”

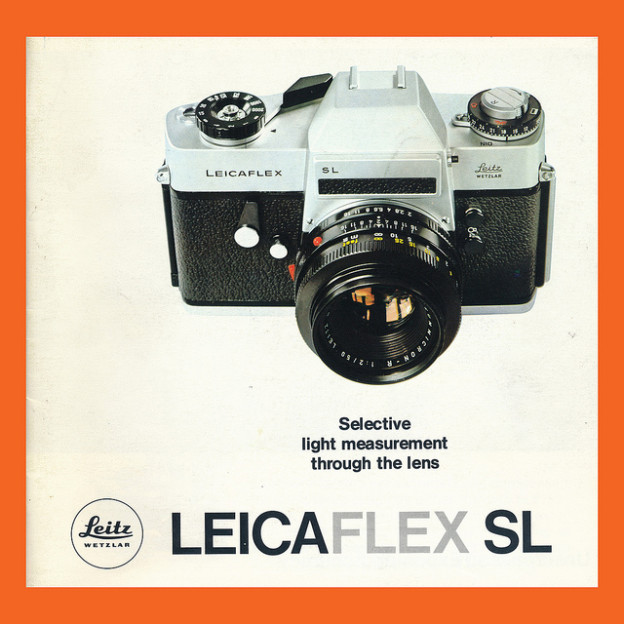

The Leicaflex SL: The Camera That Almost Bankrupted Leitz (No, It Wasn’t the M5!)

I love the Leicaflex SL, but I understand its not for everybody…or even most people. It’s big, and clunky and is brick heavy. In its day it cost half as much again as its competition – The Nikon F – without offering nearly as much system versatility; no interchangeable prisms or even focusing screens, no alternative backs or motors, extremely expensive but limited optics.

Its not surprising, then, that the Leicaflex system never really caught on with professional photographers as an SLR system camera. Leitz had only reluctantly accepted the public’s move from rangefinder to SLR and was slow to market a Leica SLR camera. Nikon had beaten Leica to the punch by 5 years with its comprehensive and affordable F system, and it didn’t help that Leica’s initial ‘standard’ Leicaflex (1964-68) was hopelessly outdated upon introduction, using non-TTL metering from an opening on the face of its reflex pentaprism. Ungainly and inaccurate. By the time the SL was introduced in July of 1968, the Leicaflex system was an afterthought for most photographers.

Given the late start, It also didn’t help that with the introduction of the SL Leitz chose a commercial policy of selling the SL and SL2 bodies at a cost below the cost of manufacture i.e. for every one they sold they lost money. The hope was that the money lost on bodies would be made back on the sale of Leitz lenses. The fact that Leica lost money on every Leicaflex sold should tell you something about the camera itself: while the Nikon F with metered prism sold, presumably for a profit, for $400, the SL sold, at a loss, for over $600. Pick one up and use it, even today, and you’ll understand why it cost Leitz so much to produce the SL.

As a teenage boy coming of age photographically in the early 1970’s, what I desired was a Nikon F, only because the Leica M5 was simply too expensive to contemplate. I never much thought of the Leicaflex SL. Seeing it in the store advertisements in the backpages of Modern Photography and Popular Photography, It seemed a brutalist Teutonic oddity that even Leica never totally embraced, it and its lenses priced in the stratosphere. Leica ceased production of the Leicaflex in 1976 and thereafter concentrated most of its efforts on the M system, a decision that at the time seemed suspect but now appears inspired.

In 1976, as an 18 year old, I purchased my first Leica, an M5 bought new at a discount (but still expensive) price from Cambridge Photo in NYC. In 1984 I purchased one of the first production M6’s. Since then I’ve owned and operated almost ever M model made, and currently own an M2, M4 and two M5’s. But I never much thought of the Leicaflex; it was only recently, almost as an afterthought, that I discovered the classic simplicity of a Leicaflex SL. I met a nice woman who was selling her father’s camera collection. Her father had owned 3 camera stores in the Boston area in the 60’s and 70’s, and he had been a Leica enthusiast. He had set aside a boxed SL with 50mm Summicron R and Leitz leather camera case and used it infrequently, if at all. It looked unused. I paid less for the entire boxed affair than most people pay for a smartphone they’ll throw away in 2 years.

The SL just may be the high water mark of Leitz’s traditional hand-built manufacturing prowess. What it lacks in aesthetics it more than makes up for in feel and workmanship. As with the M’s, nothing superfluous has been added for commercial appeal. The Leicaflex SL is mechanical simplicity defined, with a heft and feel that makes the F seem cheap and flimsy by comparison. Close you eyes and wind on the film and you’ll swear you have an M in your hands. Look through the viewfinder and find a size and brightness that puts the F to shame with its low light focusing capabilities. Plus you get to use the wonderful, albeit expensive, Leitz lenses.

Ultimately, I had to decide: was my perfect SL to be a collector’s shelf queen, or would I use it? It was easy enough decision after I’d handled the SL – you use it and you marvel at your fortune in owning such a wonderful precision instrument.

Garry Winogrand’s M4

Born in 1928 and died in 1984, Winogrand is considered by many to be one of the most influential American photographers of the 20th century. By the early 1970’s when he purchased this M4, he was shooting roughly 1000 rolls of film a year, a pace he accelerated until his death from cancer in 1984.

While Winogrand is known for his wide angle vision (many of his iconic photos were taken with a 28mm Elmarit) he typically carried two camera bodies with him, one with a 28 and one with a moderate telephoto. This particular M4 was produced in Wetzler in November, 1970, which means it probably saw 12 years and approximately 15,000 rolls of concentrated use by Winogrand.

According to Stephen Gandy, this M4 passed to one of Winogrand’s friends, who still uses the camera. I’m pretty certain Winogrand would have wanted it that way.

The M5. Leica’s Misunderstood Masterpiece: A Revisionist History

In 1971, Leica introduced its successor to the M4, the Leica M5. In development since 1966, the M5 represented a tour de force of then current rangefinder technology – it was the first metered M camera and the first 35mm rangefinder to combine interchangeable lenses with a through the lens (“TTL”) metering system. Among its other design innovations, its viewfinder incorporated a coupled light meter and shutter speed data in the viewfinder itself, it relocated the ungainly rewind crank of the M4 to the left end of the base-plate, its shutter speed dial overhung the front of the camera so you could set shutter speed while keeping you eye to the viewfinder, and it located the carry-strap lugs both at the left end of the camera so that the camera would hang vertically rather than horizontally when worn. It was also the first M camera to use black chromium for the finish of its black versions (much more durable than the black enamel previously used).

It’s semi-spot meter utilized a 8mm diameter double cadmium sulfide resistor located on a carrier arm centered 8mm in front of the film plane. When pressing the shutter release, the carrier arm swung down parallel to the shutter curtain and hid in a recess below the shutter itself. It remains, to this day, the most accurate meter ever put into a Leica M film camera. The M5 viewfinder used the same 68.5 base length and .72 magnification as the M4 with the added feature of viewing the shutter speed and match needle metering.

So, why is the M5 commonly considered a “failure,” the camera that almost bankrupted Leica? Anecdotal testimonies claim that M5’s sat on dealers’ shelves for years after production stopped in 1974 after only 4 years. I purchased my first Leica, an M5, new in 1976, 2 years after its date of manufacture. I remember a steep discount to the official retail price.

The answer, I would claim, is not so much its aesthetics or its size (the two most common explanations for its demise) but rather a confluence of factors, both internal and external to Leica, a confluence that would have doomed the M5 in whatever guise Leica chose to go forward with its M series.

The first reason is simply the tenor of the times photographically. By 1971, rangefinder technology was seen by both professional and amateur as an antiquated throw-back with numerous disadvantages. Professionals had increasingly embraced the Nikon F system and its excellent but affordable optics, and amateurs had followed the lead and made SLR’s dominant in the 35mm market. Even Leica had bowed to the future, although reluctantly. At the beginning of the 1960s, Leitz continued to believe in the inherent advantages of the rangefinder over the SLR, but found it necessary for their continued relevance to produce and market their own SLR system, the Leicaflex.

The second reason, and I think the most apt, is Leica’s decision to produce the bargain priced Leica CL system in conjunction with the M5. Leica sold 65,000 CL’s between 1971 and 1974, mostly to the amateur market, at the same time it was marketing the M5 to professionals. As such, the CL cannibalized a large portion of the market the previously addressed solely by the M series. The production numbers point to this conclusion: Leitz sold approximately 57,000 rangefinder cameras in the initial 4.5 years of the M4’s production (1966-1971) and 92,000 rangefinder cameras in the 4 years of the M5’s production. The CL accounted for more than 2/3rds of those sales, driven mainly by a price 1/5th of the M5. The truth of the ex post facto justifications for the modest sales of the M5 (i.e. it didn’t look like a traditional M) is belied by the obvious fact that the CL didn’t look like the previous M’s either and yet it sold briskly.

It was only with the appearance of Japanese Leica collectors in the 1990’s that demand and prices for the M5 rose to levels of other M’s. Unfortunately, the M5 has continued to labor under the stigma be being a “failure.” If you’ve ever used an M5, you’ll know its a wonderful camera, the last of the true Wetzler M’s built without compromise. I even think its a beautiful camera, especially the chrome version. Whatever you think of its aesthetics, it certainly doesn’t deserve the lingering stigma attached to it.

Lee Friedlander Pays Madonna $25 For a Nude Shoot

In 1979, Madonna Louise Ciccone was a 20-year-old dancer struggling to make ends meet. Lee Friedlander placed an ad in the Village Voice seeking nude models. Ms. Ciccone, who at that time was working at a Dunkin Donuts in Manhattan, answered the ad, and spent an afternoon at Mr. Friedlander’s apartment/studio, where he photographed her with a Leica M and 35 and 50 Summicrons.

In February, 2009, a print of one of the photos sold at auction for $37,500.00.

Robert Frank and the Leica Legacy

Would Robert Frank be using the latest digital Leica M if he were working today? Who knows, although I doubt it. He probably couldn’t afford one, certainly if he were unemployed and making ends meet on a Guggenheim fellowship. I suspect, were he travelling the States with Mrs. Frank today, updating his classic The Americans, he’d be driving a used Hyundai and shooting a digital point and shoot he bought second hand on Ebay. Or maybe, just maybe, he’d be using a beater M and shooting Arista Premium 400 he bought bulk from Freestyle.

Frank wasn’t much concerned about his equipment. He had started out using a Rolleiflex TLR but had switched to a Leica IIIc because it was small and unobtrusive and better suited to his documentary aesthetic. Its 50mm Sonnar was seriously out of whack, offset sufficiently from the film plane that it was exposing the sides of the image around the film’s sprocket holes.

This is not to accuse Leica of being cynical or disingenuous with its ad campaign for the latest M digital. Frank did use a Leica for some of the iconic photos of the twentieth century, and he continued to use them through the 1980’s, after which he dropped out of site photographically. (I recall seeing him in NYC in that era, sitting with 2 Leica M’s on a table next to him.) They’ve earned the right to claim Frank’s loyalty.

Frank was a visual purist. It was only the image that mattered. And I don’t mean that in the sense of what digital photographers mean by ‘image quality.’ He couldn’t care less about sharpness and resolution and bokeh and all the other foolish things current photographers mistake for quality. His best images are remarkably free of such pedestrian concerns. It was always about whether the image spoke to you.

Leicas have always been expensive. They’ve always prided themselves on the quality of their optics. But there’s been a sea-change in the public’s perception of what is unique to a Leica rangefinder since the advent of the digital M. Traditionally, Leicas were prized by Frank’s generation because they were small, and quiet and discreet. Their Summicrons and Elmars and Elmarits were excellent lenses, well-made and optically sound, but they weren’t that much better than the 50’s and 60’s era offerings from Zeiss and Nikon. (Many of the iconic Americans photographs were taken with a Zeiss Sonnar.) What mattered was seeing the picture and getting the picture, needs that a small pocket-size camera that could scale focus met well.

Now Leica stands for exclusivity and unparalleled, over the top optical excellence. Nothing wrong with that. But it wasn’t why Robert Frank used a Leica, and it wouldn’t be today if he were still photographing.