That’s Garry Winogrand on the Left, Photo by Tod Papageorge

By Tod Papageorge from https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/7084

I first met Garry Winogrand at the beginning of 1966. Although I was a dozen years younger than he was, we quickly became close friends and, soon enough, were photographing together on the streets of New York. In the beginning, I found this a little strange; for me, making photographs was something to be done in private, if only because it required such tremendous concentration to have any hope of doing it well. But I soon realized that meeting with Garry and walking the streets with him didn’t mean that I would have to give up the idea of working autonomously: we simply spread out, typically separated by about half a city block, and worked independently. Manhattan was rich enough in photographic possibility that neither one of us felt constrained by the other: there was more than enough to see and be excited by. And then, every once in a while, we could stop and have coffee together and indulge in the pleasure of talking about what we’d seen, usually in the Museum of Modern Art café.

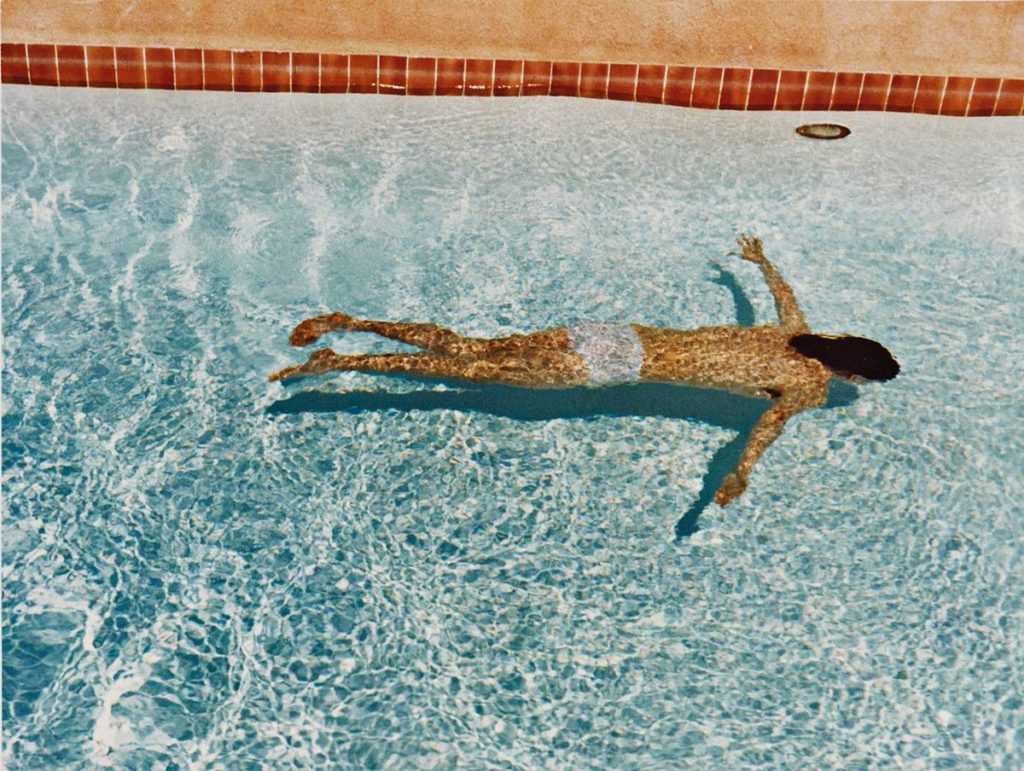

And so, one Sunday, on an early spring day about a year after we’d met, Garry and I found ourselves walking through the Central Park Zoo. I was 20 or 30 yards ahead of him when I noticed a handsome couple walking toward me—they looked like fashion models, in their 20s, both well-dressed—improbably walking with a pair of chimpanzees who were as immaculately attired as they were (the animals even wore shoes and socks). A New York City piece of strangeness, it seemed to me, strange enough to take a picture. So I did.

Then, bang!, I felt myself being pushed in the back away from this odd little group. A real shove, unfriendly, hard. And, of course, it was Garry, camera already up, making pictures, who’d done it.

Garry Winogrand, Central Park Zoo, New York, 1967

Obviously, he was seeing something that I hadn’t seen, and what he was seeing was important enough to him that he was willing—for the first and only time in all the years that I knew him—to aggressively lay hands on me. I was shocked, of course, but once I saw that Garry, and not one of the Sunday strollers rushing by me, was responsible, I forgot about being angry or even irritated: he was my friend, I rationalized immediately, and must have had his reasons for momentarily acting as if he’d never seen me before.

By now, both chimpanzees were off the ground (as my picture shows, one had been toddling between the couple when I first saw the group), and I finally noticed that the man in the little quartet was black, and the woman white and blonde. I’d already recorded that fact with my eyes, I’m sure, but what it may have meant, or could mean, in a photograph, was something I hadn’t had the time or the consciousness to process.

Garry Winogrand, however, had obviously processed the fact: where I saw only the possibility for a joke that, at best, touched on the crazy-quilt nature of city life, you could say that Garry, by not so much seeing the group itself but instantaneously imagining a possible photograph of it, placed meaning, particularly as it might gather around the question of race, at the very center of what he was doing.

In other words, quite apart from whatever Sunday pleasure or notion of self-advertising had actually brought that couple together with those two animals, Garry’s quick mind construed from their innocent adjacency a picture (or the projection of one) that could suggest the improbable price that the two races, black and white, might have to pay by mixing together. He was speculating, of course, playing an artistic hunch, but a large and important enough one that he felt it was worth pushing his friend aside for. So he did what he had to do, and then, a moment later, I answered by making a picture of him standing by the same family group as they continued their stroll through the zoo.

Note Garry’s smile, like that of the cat who’d swallowed the canary, and also the stub of a cigarette sticking out between his fingers, which, with that grin, suggests a man deep into the moment, full of the pleasure of it, more than a truth-telling artist who had just produced an image that can arguably bear comparison with the best graphic work of Goya. For example, here, making such an argument, is Hilton Als, an African-American writer, describing this picture at the conclusion of an essay called “The Animals and their Keepers”:“In the photograph,” he says, “we see a white woman and a black man, apparently a couple, holding the product of their most unholy of unions: monkeys. In projecting what we will into this image—about miscegenation, our horror of difference, the forbidden nature of black men with white women—we see the beast that lies in us all.”

Of course, when he made this picture, Garry had no proof that it would mean anything at all. His film would have to be developed and, even then, he wouldn’t have photographs to see until he’d produced the small 1 X 1 ½ inch frames of each picture on a contact sheet that he could read one by one with a magnifying glass. In other words, as the digital age is now tempting us to forget, there was, and is, built into the usual photographic process a significant distance, both of time and physical immediacy, between an event and a photograph of it. This is a distance that, for Garry Winogrand, had virtually ontological implications, as suggested in the carefully chosen language of his well-known statement, that “I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed,” or, to elaborate it clumsily, “I photograph [at a given moment] to find out what something will look like photographed [when I eventually have the opportunity to study it in an undetermined future].” When Garry finally developed that film, then, it was not in the spirit of hoping to claim a masterpiece of photography, or simply a good picture (which never really interested him), but, in this particular case, to determine if the possible narrative he’d sensed in the three-dimensional, shifting space of the zoo had, in fact, been confirmed within the reduced two dimensions of his picture—in other words, to judge whether a photograph that more or less depended on a pair of well-dressed chimpanzees to become actors in a provocative, ambiguous tale had, somehow, in the shift from world to image, managed the feat. To put it another way: he was less interested in the ultimate “success” of the picture than in what he called the problem of making it, a problem he had consciously set for himself in the antic moment of pushing me out of his way. As he put it to a group of students a few years later, no doubt remembering this picture as well as others, “well, let’s say that for me when a photograph is interesting, it’s interesting because of the kind of photographic problem it states—which has to do with the . . . contest between content and form. And, you know, in terms of content, you can make a problem for yourself, I mean, make the contest difficult, let’s say, with certain subject matter that is inherently dramatic. An injury could be, a dwarf can be, a monkey—if you run into a monkey in some idiot context, automatically you’ve got a very real problem taking place in the photograph. I mean, how do you beat it?”

As it turned out, Garry never reached a conclusion about whether or not he’d solved the problem, or question, that the picture we’re considering here had posed for him. Although it has become canonical, and is, perhaps, the single photograph now most associated with his body of work, the fact is that, in his judgment, it remained an aesthetic question mark until he died. For example, “The Animals,” his first book, comprised of photographs made in zoos, was initially published in 1969, two years after he made the picture, yet it’s not included in the book, a piece of evidence, that, while not conclusive (since John Szarkowski was the publication’s principal editor), at least suggests that he wasn’t sure enough of it to insist that it be added. But he didn’t really worry about such things: there were too many other pictures to think about, too many kinds of lessons in his pictures to unravel and learn from, too many problems put into play as he made them. As he understood it, photography was much larger than he was, and his pleasure as an artist was to unremittingly study it.

As I’ve already stated, Garry was remarkably unmoved by conventional notions of success, even artistic success as typically measured by exhibitions and awards. “You learn from work,” he’d say, and, further, “I really try to divorce myself from any thought of the possible use of my photographs. Certainly, while I’m working, I want them to be as useless as possible.” Which, turned around, also suggests that, as he understood the issue, any one of them could be judged a success by virtue of the possible lesson it might teach him. Failure, as much as success, was an irrelevant concept to him.

Garry could be scathing and utterly dismissive in his criticism of other photographers, however, if their work failed to measure up to what he felt intelligent photography should be. For example, he scornfully rejected a body of work by one of his contemporaries that concentrated on a minority community in Manhattan, by saying that “You expect the people in his pictures to tap dance and eat watermelon,” proof of how aware he was of the power of photographs to reduce black subjects to smothering cliché. But he conducted his own personal investigation into the nature of the medium in what was effectively a judgment-free zone where his interrogation of photography and the making of his pictures were effectively one and the same activity: as I understood it then, and still do, he was the pure artist, or as pure as one could be who was committed to conducting his researches in the open-air theater of the corporal world. Also, he began to teach during this period (at virtually the moment I met him in 1966) and, as part of his teaching, to formulate the series of cryptic, but powerful, aphorisms about photography that, even now, any young photographer would be foolish not to commit to memory before considering the question of whether or not to reject them. So, yes, as the curator of this exhibition, Leo Rubinfien, quotes him as remarking near the end of his life in Los Angeles, Garry was a student of America. Yet, during his most prolific and creatively fulfilling years as a photographer in New York, I would suggest that he was more nearly a student of photography whose observation at the time that “a photographer’s relationship to his medium is responsible for his relationship to the world is responsible for his relationship to his medium” traces an eloquent circle of causation that begins and ends with the photographer’s deep identification with his medium. Certainly, during that period, when I was seeing him nearly every day, he was very much the genius/apprentice implied in that remarkable comment, instructing himself, exposure-by-exposure, about the many different ways photographs could look;how their frames might drop around his subjects, or even tilt as if the photographer was falling or out of control. And, more, how free he could be, and let his subjects be, to move and claim their place in his pictures as if they were expressing their own active agency, rather than appearing to be responding to the whip of the controlling, manipulating artist. In other words, working out a method of picture-making capable of appropriately serving his fierce understanding of whatever his subject might be, whether that was America. Or a beggar in the street. Or a pair of chimpanzees and their putative parents. As he said to a student who asked him what the purpose of one of his photographs was, “My education. That’s the answer. That’s really the answer.” And then, “My only interest in photographing is photography. That’s really the answer.”

For Garry Winogrand, it was foolish to pretend that a thing and a photograph of it were, in any useful sense, one and the same, and that the photographer could no more than minimally control the way his or her pictures of that thing would look. As he understood it, the lens and its unforgiving memory; the world, full of color and dimension; and the photographer’s own limited ability to absorb all of the information arrayed in his or her viewfinder from edge to edge determined an effect, the photograph, that would inevitably be different from the cause that created it, which is to say, the nominal subject of the picture, wild out in the world. “Photography is not about the thing photographed. It is about how that thing looks photographed,” he said. As a result of this understanding, he came to see that, far from trying to control, or even limit, that difference, it might be embraced as a way of enlarging the meaning of his pictures, by charging them with an irreducible trace of unresolved, still-sparking energy that, from picture to picture, could be seen to embody the very élan vital that prods and pushes us forward in our own daily lives. So that, in the end, the picture, in some real, physical sense, re-joins us to life, but life transformed, still palpable in its vitality (always decomposing, always rising) and, by being so, true to the chaos—or “monkey business,” as he often called it—that Garry Winogrand knew it to be.