By Andrew Molitor. Molitor is a fellow writer on photography, variously described as iconoclastic, irrelevant, occasionally right. He swears a lot. You can find him at photothunk.blogspot.com

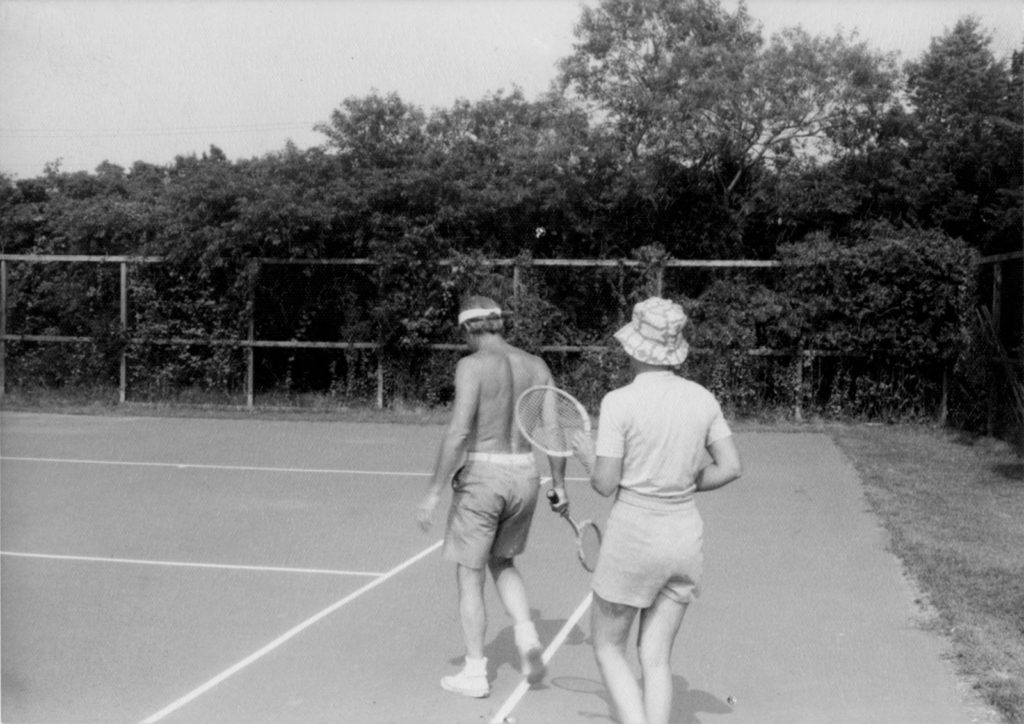

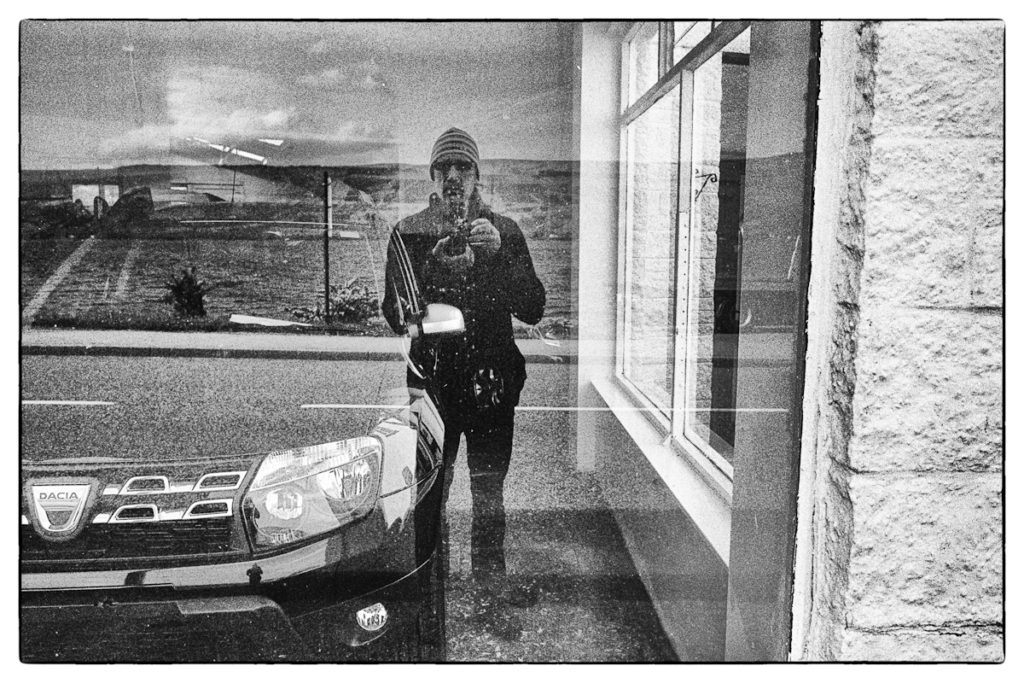

Recently, in an article in The New York Review of Books, Janet Malcolm told the story of how she had included – as a joke – an artless, banal snapshot in her book Diana and Nikon, together with a number of other photographs that had been decreed by the relevant authorities to be Art. It’s the photo above, Untitled, 1970 by G. Botsford. Interestingly enough, as time passed, Botsford’s photo started turning up here and there as an example of the “snapshot aesthetic”, itself a work of Art. Malcolm, via her off-hand joke, had decreed this photograph to be Art, and now people were willing to accept that it is Art in some meaningful sense.

This is the problem when considering photography as Art. Photography is not quite what we imagine it to be. The carefully crafted Fine Print is not, after all, the only pathway to true Art. Sometimes, a photograph can become Art simply because someone – not just anyone of course, but someone with authority within the art community – says it’s Art.

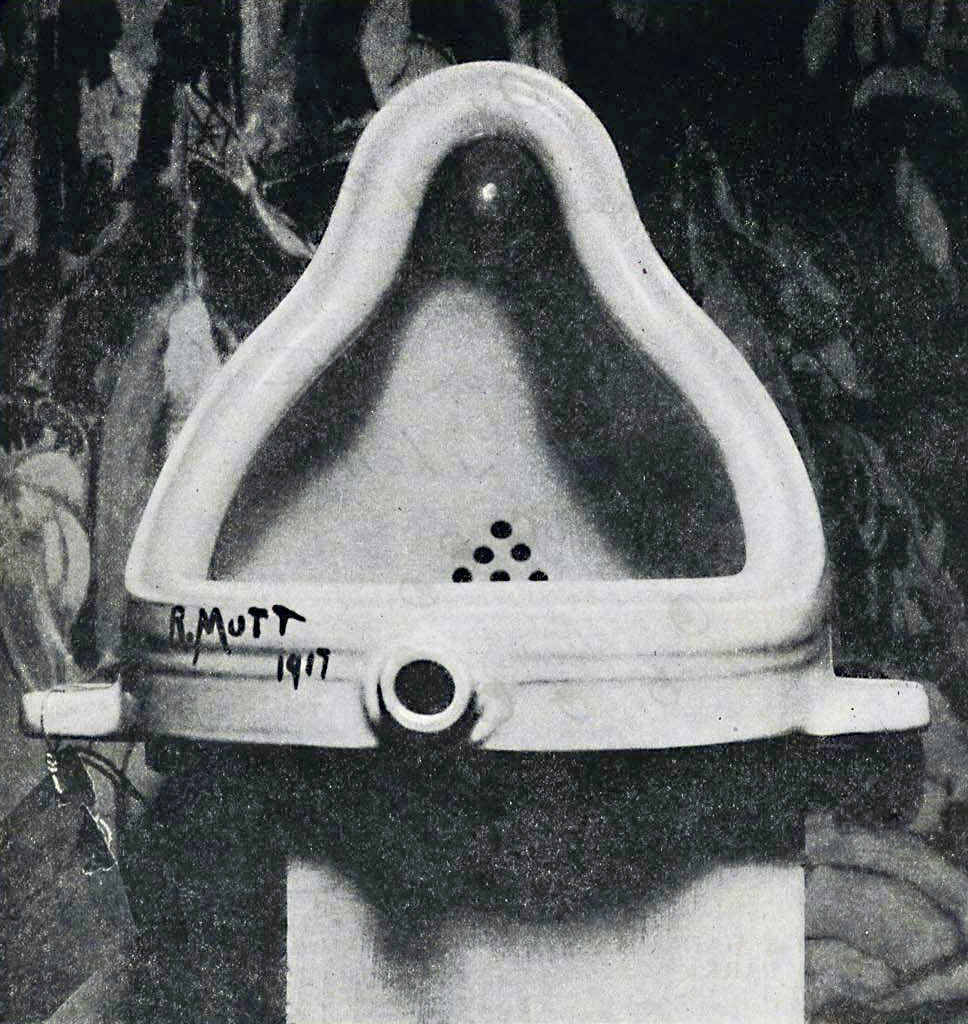

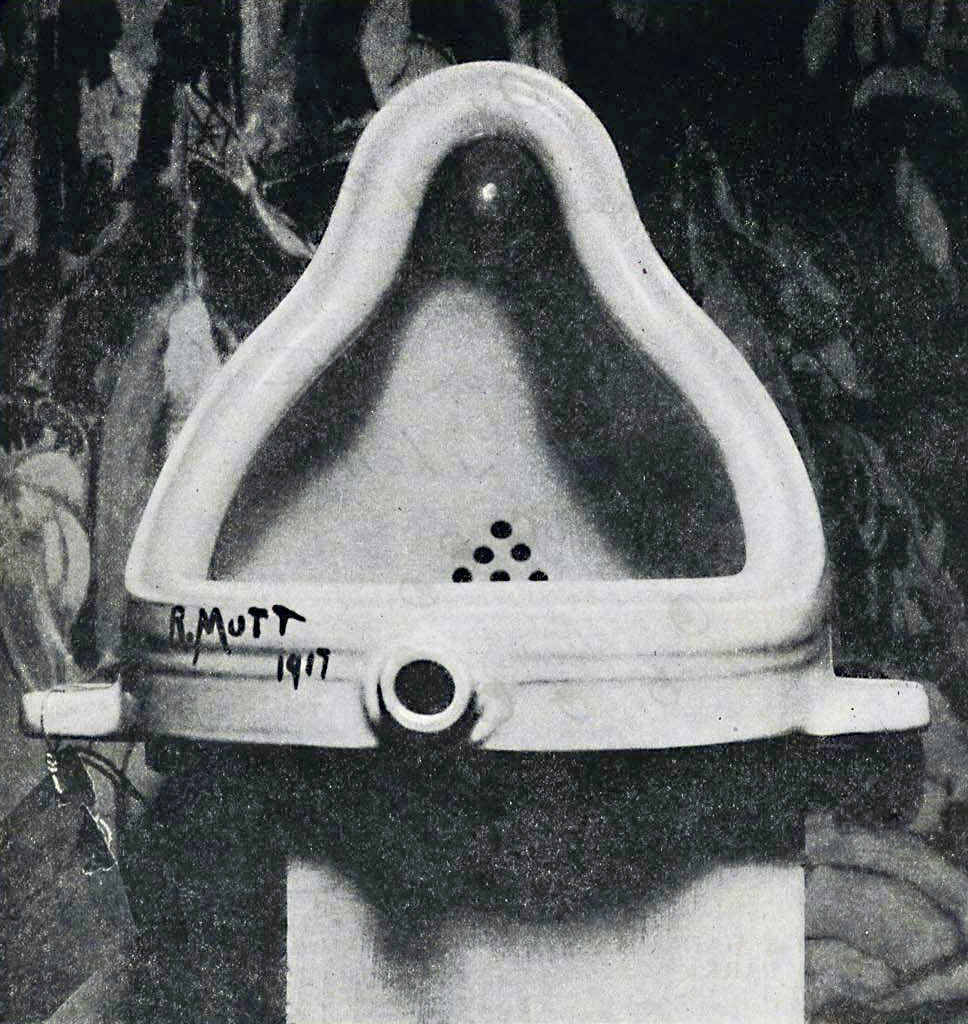

We’ve seen this before. When Marcel Duchamp exhibited a signed urinal as a sculpture entitled Fountain, he was doing the same thing as Ms. Malcolm, whether tongue in cheek we’re not sure.

What then is Art, with a capital A? Is it whatever some pointy-headed fellow with a title like “curator” or “Professor of Arty Artness” says is Art? That feels a little thin, a bit like a cheat; you intuitively feel that this can’t be right. The opposite end of the spectrum claims that Art requires skill, talent, and labor. Sculptures made out of marble, formed with infinite patience and a deep understanding of the properties of stone, now that’s Art!

The latter sort of thinking belongs to people who look at photography with a lifted brow. As noted in the previous post here, it’s this thinking that drove much of the Pictorialist movement in the Victorian era, and which drives much of the urge to “post-process” digital photographs today. It can’t be any good, the mindset goes, unless it’s had a lot of work put into it.

Duchamp’s Fountain, and Malcolm’s joke, disagree. They say that Art is merely whatever you think is Art.

*************

In my opinion, neither of these positions is correct, although each has a sort of a piece of it, a single section view. Art is whatever creates an Art-like experience. If you l ook at it, and it makes you think, makes you feel, enlarges you as a human being, then it’s Art. I would contend that this isn’t purely subjective, because usually if it works for you, it probably works for other people as well, unless you’re a complete weirdo. The appropriate term here is inter-subjective. The two acts – the first declaring, from a position of authority, that something Is Art and the second working very very hard, with great skill, to make something which you hope is Art – are both acts which can imbue an object with Artness.

ook at it, and it makes you think, makes you feel, enlarges you as a human being, then it’s Art. I would contend that this isn’t purely subjective, because usually if it works for you, it probably works for other people as well, unless you’re a complete weirdo. The appropriate term here is inter-subjective. The two acts – the first declaring, from a position of authority, that something Is Art and the second working very very hard, with great skill, to make something which you hope is Art – are both acts which can imbue an object with Artness.

When confronted with Michelangelo’s David (a product of labor and skill) as well as with Duchamp’s Fountain (a product of a simple declaration) we likely experience that sensation of Art. We feel, we think, we expand a little. The category of things that are Art is a bit fuzzy, the edges are not at all well defined. Are raindrops on a rose petal Art? Perhaps not. Is David? Almost certainly.

An object of Art is perhaps as much a subject for meditation as it is anything else, It’s not wrong to consider such an object as merely a trigger for a process that occurs inside ourselves. Michelangelo’s David or the “willfully bad” snapshot attributed by Malcolm to G. Botsford can serve equally as a focus for meditation, as a trigger for our own internal search.

All this presents something of a problem for the photographer as artist. There’s no getting around it, you can take a random snapshot of your own feet and if you can persuade Larry Gagosian to put it up for sale with an immense price tag, it will indeed be Art. Your blurry foot picture can serve as that trigger for thought, it can create an Art-like experience. In that unlikely scenario you personally had nothing much to do with this, it’s pretty much all Larry G’s work, his authority makes it Art-like. That doesn’t make it fake, though, it would, in that situation, really be Art with a capital A. Unfortunately for you, you’re probably not going to get Larry on board with your scheme.

The point to hang on to here is that there are many roads to that Art-like experience.

David would probably be pretty intense to look at, even if no art critic had ever mentioned it. The knowledge of stone, the skill with the chisel, the mastery of form were not wasted. The labor was real, and produced real results. The fact that Duchamp could, with a figurative wave of his hand, turn a urinal into a similar experience takes nothing away from Michelangelo. The well, here, does not have finite capacity.

Vast labor and skill, or the mere declaration by authority, both produce Art. By analogy, we can reason that photography’s relative ease takes nothing away from either Michelangelo, nor from the photographer. It is not necessary to labor endlessly, either mashing gum bichromate prints with your hands or fiddling around in Photoshop to make your photograph worthy of the name Art. You certainly may do either, and your labor and skill may produce results.

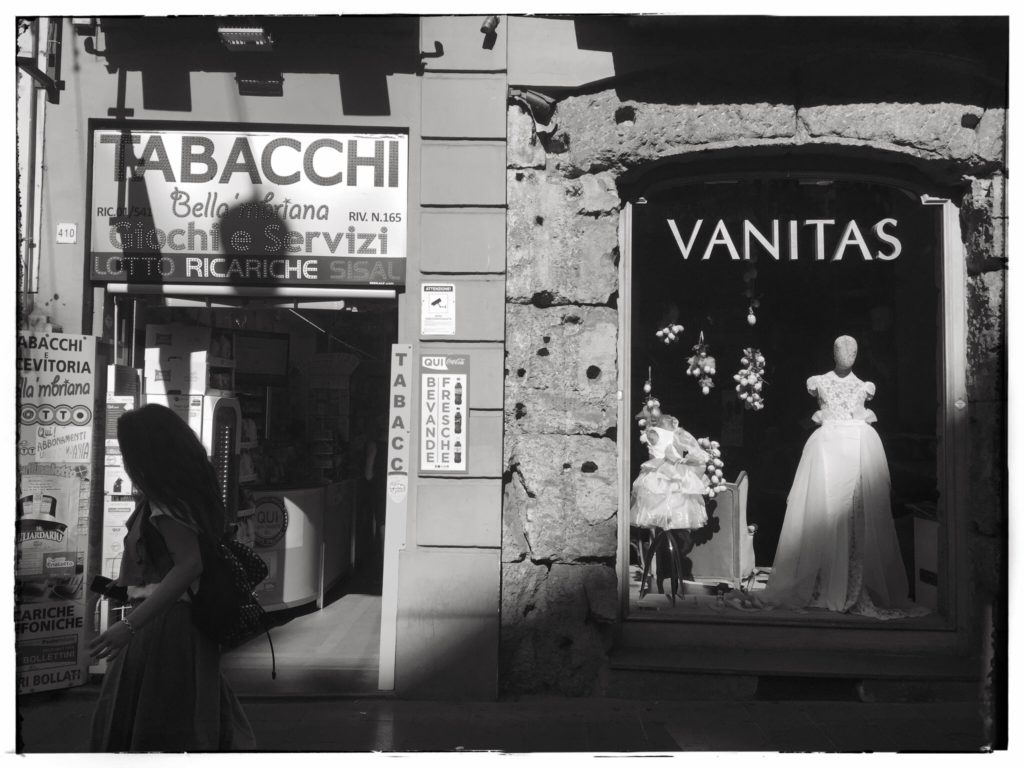

In its very essence, though, as I see it, photography is simply selection. Not to denigrate selection, it is in its own way every bit as worthy as making. In this case, selecting and making are two different activities, which ought to be viewed on an equal footing, neither being a poor cousin to the other.

This bears repeating: the act of photography, that act of selection should be considered as on the same moral plane as the act of creation that typifies a painting, a sculpture. Think of the photographer as a curator of the visual, selecting and interpreting a slice of the real for other’s consideration.

This is the essential worry photographers have about whether photography is Art. Contrary to the regularly scheduled articles about how it has just now been settled, Photography has been comfortably ensconced as an Art for over 100 years now, in part due to Duchamp and his urinal. We saw then that selecting something could indeed be viewed as co-equal with making something. Photography being, essentially, selecting, but with an optional and open-ended add-on of making, of creating, fits into this framework perfectly comfortably.

Many photographs are not Art. Looking at them generates no Art-like experience. Mostly, they’re not intended to, they’re just a document of someone’s holiday, someone’s lunch, someone’s coffee, someone’s child or dog.

What makes a photograph into Art? As we now know, Janet Malcolm declaring it to be so seems to do it. Ansel Adams demonstrated that putting a lot of work into prints might do it, producing quite a different Art-like experience. Robert Frank’s famous book partakes of a bit of both, being on the one hand a great deal of labor, but on the other hand made up largely of what appear to be snapshots, at least in the sense that they lack the lumbering and meticulous flavor of the Adams pictures.

At the end of the day, in order to be accepted into The Canon, one needs the imprimatur of some authority figure, but let us set that aside for the moment. Suppose we’re making Art for a small enough audience, and audience that will accept at least tentatively our own statement as sufficient authority. How then to produce an Art-like experience?

We’re unlikely to be able to slip that blurry picture of our own feet past this audience, they expect, demand, more from us generous though they might be. Our authority is not Duchamp’s, even with our friends. We are granted, perhaps, a bit of leeway by our friends. Our friends feel a certain openness and generosity, but are not willing to swallow just any old thing.

I think that we do it by selecting carefully, with genuine feeling, with genuine ideas. Ansel Adams, held up as the mighty technician, literally cannot shut up on this theme. It seems that almost every page of his famously technical trilogy repeats that a picture must be a true reflection of an emotional state. Oddly enough, the Zone System people rarely mention this. His pictures are indeed sublime (although, crush the blacks and see what happens).

If we have a real idea, a real feeling, a real something-to-communicate, and we allow our pictures to reflect that, then sometimes our work might just generate an Art-like experience to someone, somewhere. We might “get through” from time to time, and it’s that communication – the curation of the visible, and the aesthetic response of the viewer – that creates Art.