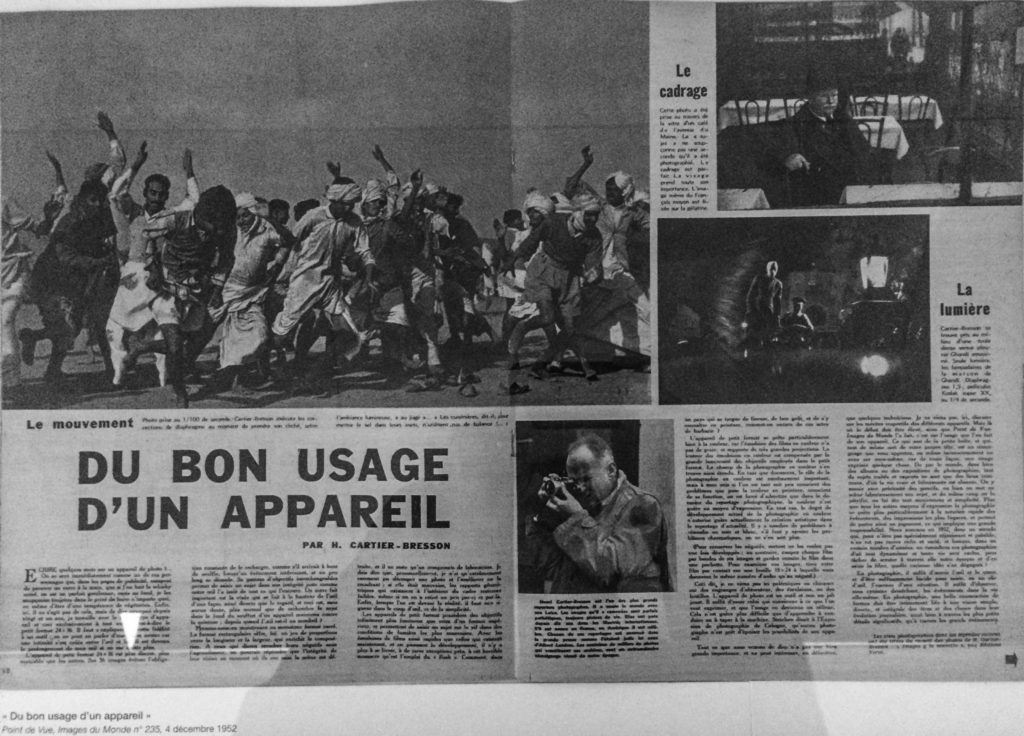

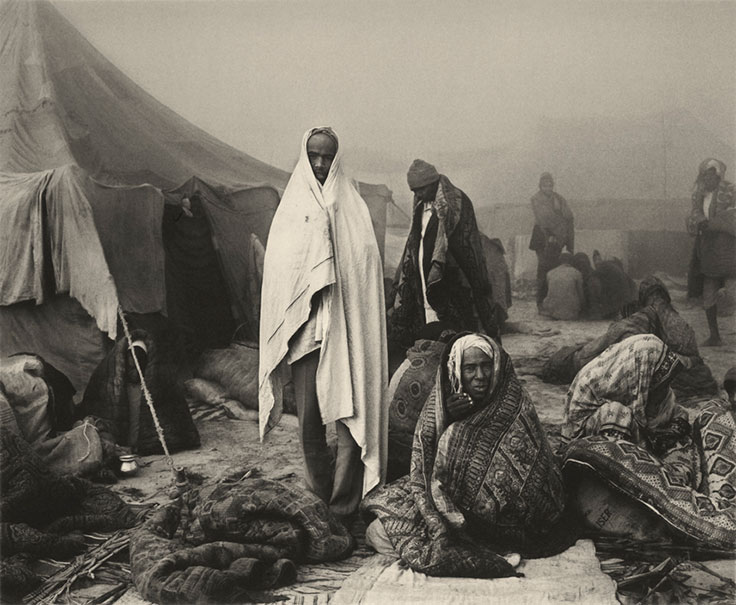

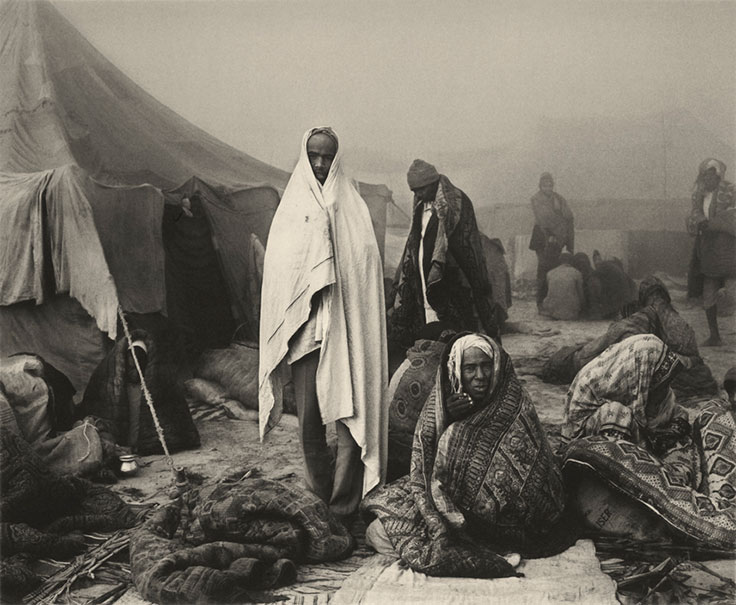

Early Morning at the Kumbh Mela, Allahabad, India, 1989. © Don McCullin, courtesy of Hamiltons Gallery

Early Morning at the Kumbh Mela, Allahabad, India, 1989. © Don McCullin, courtesy of Hamiltons Gallery

Don McCullin tells Jonathan Bastable how his present work helps him manage memories of his past. This article originally appeared in the November/December 2015 edition of Christie’s Magazine

At the back of his sunlit, peaceful house in Somerset, Don McCullin has a tiny workroom where he keeps his prints. There are boxes upon flat boxes, stacked on broad shelves like pizzas awaiting collection.

McCullin, who recently celebrated his 80th birthday, stands at a wooden plan chest, sorting through some large format ‘platinums’. ‘The print is made of platinum dust on thick watercolour paper,’ he explains, carefully laying aside the sheets of tissue between each one. ‘This batch is for a collector. They are produced by a specialist I know in Gloucester; Bailey uses him too.’

The images are breathtaking. The first one out of the box is a still life of dark mushrooms lying on a slab of chipped concrete, a shiny wine jug behind them; it is an essay in textures and surfaces. Then there is a group portrait of Indian pilgrims outside their tents at the Kumbh Mela: wrapped in their shawls and blankets, they look like Hebrew wanderers waiting for Moses to come down from the mountain.

There is a bleak and snowy view of the valley beyond McCullin’s house. ‘I love the nakedness of the countryside in winter,’ he says. ‘When leaves cover the trees they are deceiving — you don’t know the core of them.’

Perhaps the most stunning photograph in the set is a statue of Aphrodite from Leptis Magna, now an exhibit in Tripoli’s Red Castle Museum. It is a wonderful shape, the pitted torso illuminated by a single unseen bulb (‘No tripod: I had to stand stock-still for a fifteenth of a second at wide-open’). That battered goddess says a great deal about McCullin’s preoccupations: history, humanity, and the damage that humans do.

Don McCullin was born in 1935 in Finsbury Park, at that time one of London’s rougher bailiwicks. When war broke out, he — like thousands of other small children — was packed off to the countryside, where he was separated from his older sister. His experiences as an evacuee were rough, and would now certainly be classified as neglect or cruelty. But it was the dislocation that left the deeper mark. ‘I have been on the move since my mother sent me away as an evacuee,’ he says. ‘I haven’t stopped running.’

As a teenager, McCullin did his national service in the Royal Air Force, where he was given the job of processing aerial photo-reconnaissance. ‘Photography came to me accidentally. I didn’t know that was what I wanted to be. In the RAF I even failed my photography trade test.’ On a whim, during his last weeks in the forces, he spent £30 on a Rolleicord — the twin-lens-reflex camera beloved of Brassaï and Brandt: ‘I came out of the Air Force with this beautiful camera, but I didn’t know how to use it.’

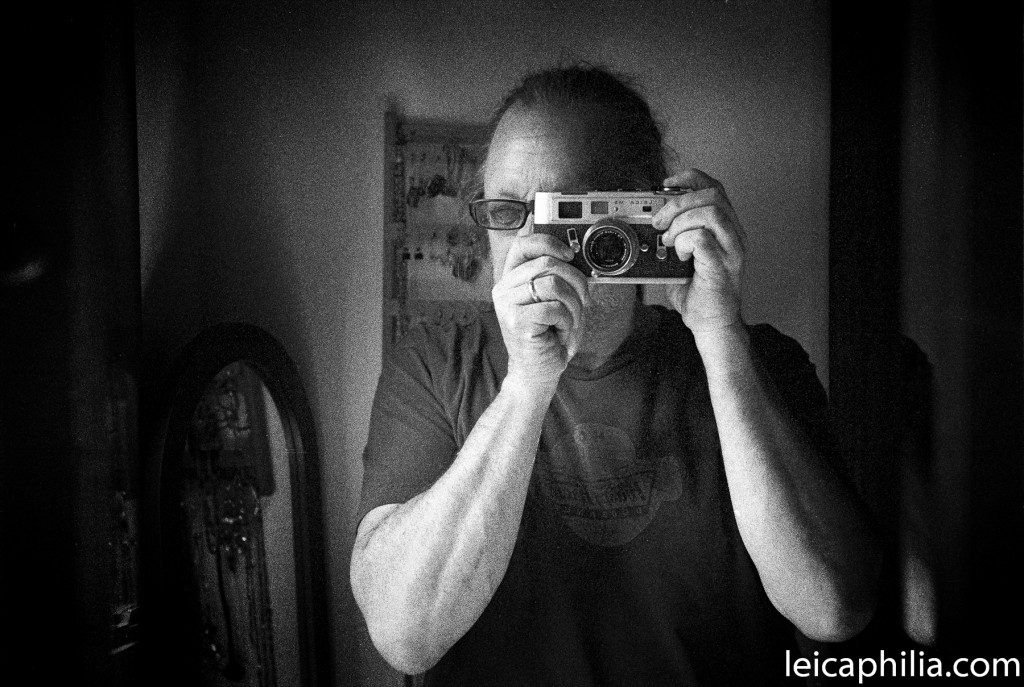

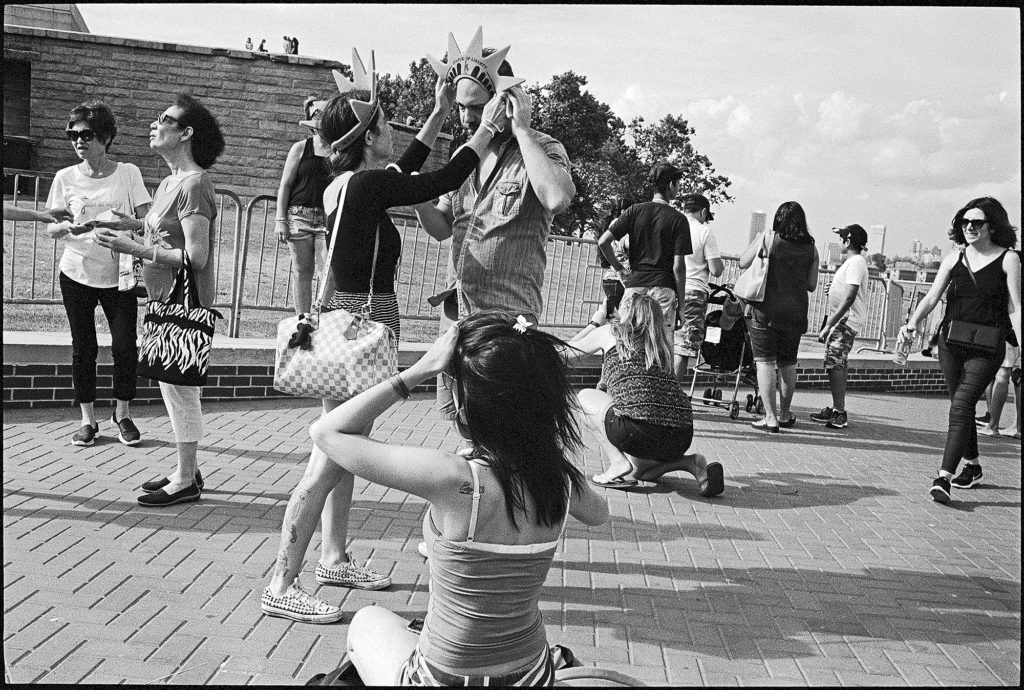

Don McCullin’s Nikon F. “I only use a camera like I use a toothbrush. It does a job.”

Don McCullin’s Nikon F. “I only use a camera like I use a toothbrush. It does a job.”

It took a perverse stroke of luck to turn that impulse buy into the beginnings of a career. One night, back in Finsbury Park, a policeman was killed in a scuffle between gangs. McCullin, who had been experimenting with his Rolleicord, took some pictures of the lads he had grown up with — though they had nothing to do with the murder.

He took his portfolio to the Observer, where the picture editor immediately saw that it said something newsworthy and worthwhile. One shot of those North London lads posing on a bombsite became McCullin’s first published photograph. ‘So my career in photography was built on violence and death from the start.’

Now he had a foot in the door of a newspaper, McCullin looked around for stories that he could pitch. It was 1961, and a political crisis was looming in Berlin, then under the military occupation of four armies — British, American, French, Soviet. McCullin told the paper that he wanted to go to Germany to cover it. Incredibly, the Observer was not interested, so McCullin went at his own expense, and shot the first days of the construction of the Berlin Wall. The pictures — which, needless to say, the paper was more than happy to print — won him a British Press Award and a regular contract.

‘That’s how life has been,’ says McCullin, ‘a series of episodes where I thought: I must go here, I must go there.’ He has a firm belief that his hunches always turn out to be right. Throughout his life, he has had the good journalist’s knack of turning up in the right spot at the right time.

‘In Biafra I took pictures of starving children. I was riddled with guilt for being there, troubled by the knowledge that they hoped I had food, when all I had was two Nikon cameras’

In 1967, during the Six-Day War, he headed for Jerusalem when the press pack went south to Sinai, and so was the only photographer present when the Israeli army took the Wailing Wall. In the 1970s — during what he calls his Hogarthian period — he shot the lost souls of Spitalfields and Whitechapel, somehow sensing that gentrification was on its way. More recently he published a beautiful book, Southern Frontiers, that explores the Roman remains strewn around the Maghreb and the Middle East — among them the very temples in Palmyra that have just been obliterated by ISIS.

The same irresistible intuition is taking McCullin to Iraq this autumn. ‘I will not be able to run any more,’ he says. ‘But you can’t outrun a bullet anyway.’ War is, of course, what McCullin is best known for. From Cyprus to El Salvador, Vietnam to the Bogside, he has probably been exposed to more armed conflict than any photojournalist of his generation — more, come to that, than most professional soldiers. But he doesn’t like to be termed a war photographer. ‘It’s like saying I work in an abattoir; it’s like being called a criminal.’

Those seem harsh self-judgments: to be present at a crime — even a war crime — is not to be complicit. But McCullin is adamant. ‘I found wars exciting when I first went to photograph them. I thought this is fun, the bullets are flying, it’s a bit Hollywood. Then I started going to wars where the civilian population was suffering the most, and that brought about a change in me.

‘In Biafra I took pictures of starving children. I was riddled with guilt for being there, troubled by the knowledge that they hoped I had food, when all I had was two Nikon cameras around my neck. I have flagellated myself over the years with conscience and uncomfortable memories — but that hasn’t helped those children. None of my pictures have saved lives.’

What are documentary photographs of human misery for, then? What can they achieve? If — as seems reasonable to suggest — their function is to bear historical witness, then to take pictures of other people’s suffering is an entirely proper thing to do.

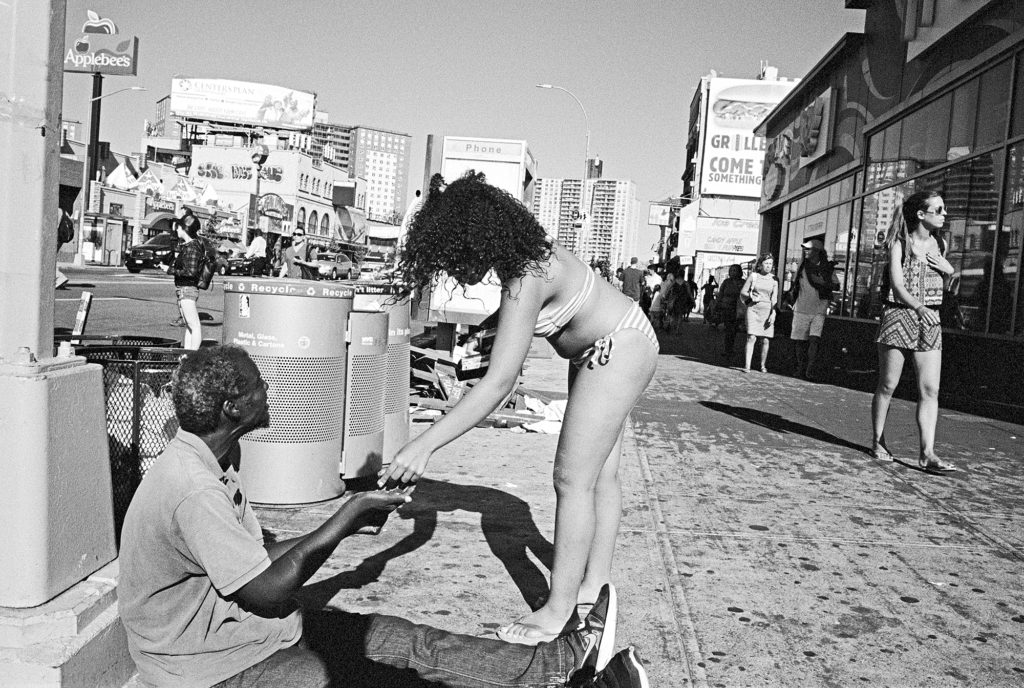

Don McCullin, Palestinian Woman returning to ruins of her house, Beirut. © Don McCullin, courtesy of Hamiltons Gallery

As for the deep unease that McCullin feels, it surely derives from the fact that — however harrowing the events of the moment — part of his attention is on broadly artistic matters: composition, light, narrative, visual impact. McCullin pauses before he responds to this idea. ‘I was once in a stairwell in Beirut,’ he says. ‘Some Palestinians had been dragged out of their rooms — they were going to be shot. And as the shooting began, the men looked up and raised their hands like this…’ He lifts his own hands in a gesture of supplication, the five fingertips oriented upwards and almost touching, so that they make a shape like the head of a tulip. ‘They were calling to their God,’ he says.

So the photojournalist in him saw these men at the moment of their death, and what stuck his in his mind was their pose — and with it, the instinctive knowledge that this could be a good picture? ‘Yes, but I wasn’t looking for a good picture; I was looking for truth. There is nothing good about photographing a man being murdered, nothing at all. I am not an artist, and I don’t call my work art, I call it photography. When people say my pictures are “iconic”, that doesn’t mean to say it is art. I would rather people said that my pictures were memorable, or even that they can’t bear to look. Though of course I do want people to look, to have the eye contact, to have the connection with suffering that any decent person should have.’

‘One of the most stupid things people ask me is: do you have a death wish? I feel like saying, why don’t you go to hell?’

That eye contact is central to McCullin’s work, so much of which is portraiture — albeit portraits of people in distress or in extremis. He has never used a long lens: proximity is for him an essential part of the transaction, as if the subject were co-creator of the finished picture, or at least a collaborator in it.

That is certainly true of his best-known portrait, a close-up of the blank, drained face of a shell-shocked GI in Vietnam. ‘I am slightly sick of that one. But yes, everything is in the eyes of people. The truth of pain is in the eyes. I try to hold the eyes, to get them to look into the camera and trust me. So I need to be close enough to be trusted. That’s what makes it powerful, because the eyes become accusing.’

McCullin says that his platinums are an attempt to bring some balance to his work, and maybe to his memories. After all, a landscape cannot cry or bleed. ‘This work is therapeutic,’ he says. ‘I couldn’t be happier than when I am standing in the cold on Hadrian’s Wall, waiting for the right light. The platinums are the essence. They are as far as you can go with what I am trying to do and say.’

Dew Pond, Somerset, 1988. Gelatin Silver Print. Dimensions variable © Don McCullin / Contact Press Images.

So can these pictures, at least, be called art? ‘No, I call them photographs. There are photographers in America whose prints fetch $100,000 a time, and they all call themselves artists. Why can’t they be content with the word “photographer”?’

He puts away the platinum prints, then goes out into the garden to look at the view down the sloping dell to the trout stream and his orchard. ‘One of the most stupid things people ask me is: do you have a death wish? I feel like saying, why don’t you go to hell? My father died when I was 13, and that left me really angry. I have kept that anger about death. When I see children dying, I think: who can I blame? Who can I punch?’ He pauses again. ‘I am coming to the edge of the crater, and I think about life quite a lot. The other day I was wandering around out here and I thought, you know what, this is rather nice. I want to live as long as anybody. And having seen so much death, I want to live twice as long.’